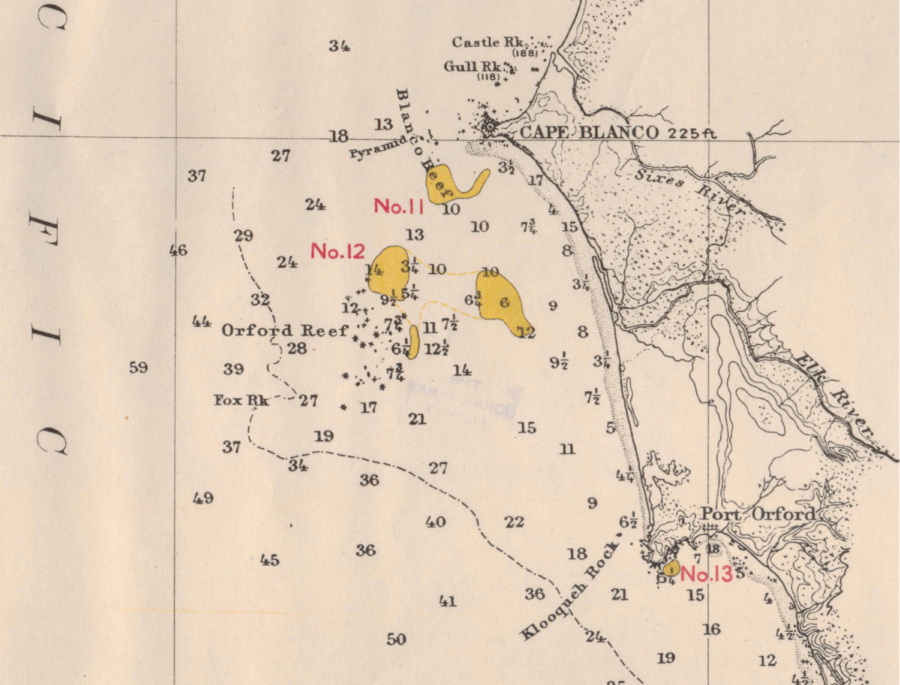

The University of Chicago Library digitized rare 105-year-old maps documenting kelp forest populations to support research on the relationship between kelp populations and the environment.

Handled carefully by the Library’s Preservation team, the 27×21-inch bound map folios were scanned by photographer Michael Kenny and Head of Digitization Kathleen Arthur and can now be viewed as PDFs available through the library catalog.

Ecology and evolution professor Catherine Pfister and her colleagues at the Washington State Department of Natural Resources have used the maps to determine the change in kelp populations along the coast of Washington, by comparing the maps’ data from 1911 and 12 to modern aerial censuses dating from 1989 to 2015.

Comparisons between data from these two periods show that kelp populations have similar densities today as they did at the beginning of the 20th century—with notable exceptions in areas close to high-density human population centers.

Many species depend on kelp presence, which researchers commonly consider a foundation species. Kelp is resilient despite an average seawater temperature increase of 0.72 degrees Celsius.

While other ecological studies have demonstrated the adverse effects of climate change on marine foundation species, such as salt marshes, seagrass beds, and mangroves, the relative stability of kelp populations is surprising.

“Coastal areas of Washington are characterized by ‘upwelling’ of cold, nutrient rich waters from deeper areas,” Pfister wrote in an e-mail to The Maroon, offering an explanation for the kelp persistence. “I would expect these areas where I have worked to be some of the least affected by warming of the surface oceans, compared to other locales.”

Though most areas revealed kelp persistence, analysis showed reduced kelp populations in Puget Sound near Seattle and Tacoma, spurring inquiry around the possible environmental impacts human interaction may have on kelp.

“Why these kelp beds in closer proximity to population centers have declined is not as clear, and we are currently interested in this,” Pfister said. Her team’s research concludes that human interaction with the environment may have greater effects on kelp population than changes in regional climate.

Commissioned by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, the maps were created in 1911–12 to locate kelp beds to later be harvested and used to make potash, a mixture of potassium and salts used in fertilizer and ammunition powder.

At the time, the United States sourced its potash from Germany, and, in the face of increased political tensions, the government began seeking alternative potash sources.

George Rigg, an ecologist from the University of Washington, navigated the coast documenting kelp beds on a 50-foot boat with a 40-horsepower motor for two years to complete the maps.

With only around 15 copies of the kelp forest maps held by institutions in the United States, digitization of the maps will make them easily accessible and useful for future studies.

Pfister said that since the early 1900s, when the maps were created, many marine ecosystems have changed due to large quantities of shipping traffic, oil spills, and the use of herbicides and fertilizers.

“The maps give a rare glimpse into this marine ecosystem,” Pfister said.