The committee behind the Olivier Award dubbed Yasmina Reza’s God of Carnage a comedy. Maybe they’d find a play about the the Trump presidency, another noisy example of Neanderthalic human instinct sprayed into a megaphone, pretty funny as well. There is something about watching people lose it, so far gone as to scream into each other’s faces, that can feed a deep, primordial hunger and keep us going in the same way a TV-binge day can make the coming workday a little easier to swallow.

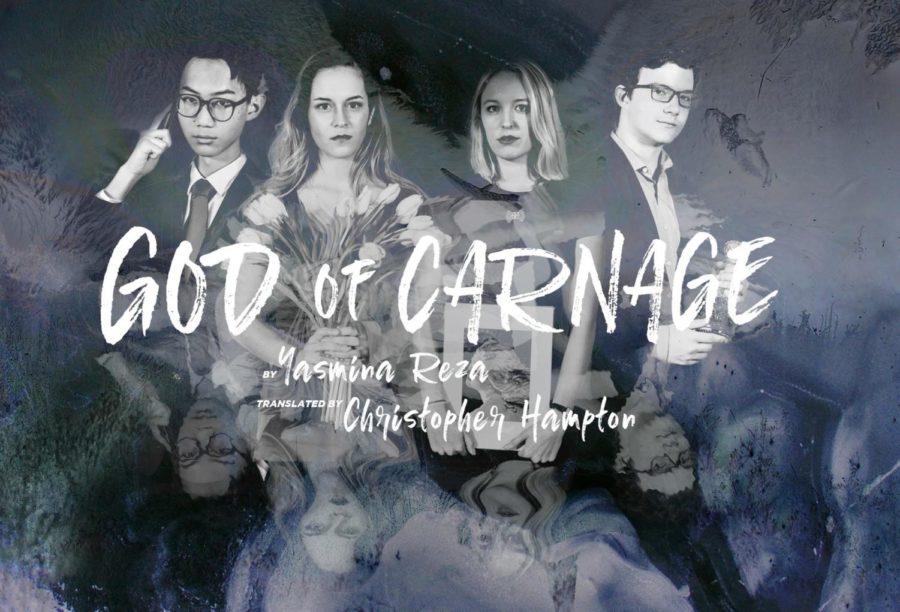

Satisfaction of this sort of is abundant in University Theater’s (UT) production, which went up this Thursday. In the play, directed by fourth-year Brandon McCallister, two couples of very different means navigate touchy questions about how to approach a dilemma: the fact that Alan (first-year Rex Lee) and Annette’s (fourth-year Margaret Lazarovits) son knocked two teeth out of Michael (first-year Brandon Powell) and Veronica’s (fourth-year Natalie Pasquinelli) boy with a bamboo stick. Annette does “wealth management,” while Alan is a lawyer so stapled to his cell phone that he would answer it even if he were on fire. Michael distributes toilet seats and home goods, while Veronica is writing a very earnest book about Sudan. Annette and Alan buzz with entitlement, Michael and Veronica with righteous hurt. The play is spring-loaded from the beginning.

Sure enough, we get about five civilized minutes before the two sides have descended into a snarling guerilla warfare that elicits a potpourri of insecurities, angers, and petty pique. It is hard to say who unleashed the barbarism: maybe it was Alan, who interrupts other characters to advise a pharmaceutical company whose product leaves patients “bumping into furniture.” Maybe it was Annette, who vomits on Veronica’s prized, pretentious coffee table books (vomit courtesy of props designer, third-year Eren Ahn. Insider’s scoop: it’s a mix of mashed potatoes and fake blood, specially formulated to wash easily out of formalwear).

Really, the question of blame hardly matters. Part of the play’s joy is how easily it surrenders to its lowest instincts. Veneers of politeness peel like wrapping paper, and suddenly the stage is populated by inner lives too busy weeping, screaming, or taunting to think about how someone else feels. It is refreshing to see the teeth (and everything else!) come out—and a little frightening, too. Veronica captures the question nicely: what’s the point to civilization in the first place?

Everyone seems to have a different answer, and most of them prove the good of social decency by showing what happens when it’s gone. Aggro-lawyer Alan says he follows the “god of carnage,” a force of domination who justifies his hyper-competitive jockeying and might explain the armchair pleasure he gets from throwing wrenches in other people’s works. Aggravation is provoked by all characters, and the wear on old bonds begins to show. New alliances form between members of supposedly opposing teams: sexism pulls the women together against the men in an alliance that crumbles when an appreciation of merciless honesty brings Veronica and Alan together against their more diplomatic spouses. But there is too much insecurity, anger, and ruthless, zero-sum competition arcing through the air for any connection to last more than a few minutes. Without tact, bonds as intimate as marriage become fuel for conflict, not emotional refuge. It’s funny to watch, but like seeing a couple vent intimate arguments in public, there’s something embarrassing and a little scary about it too.

“Carnage” runs for a single 55-minute act and features four characters who never leave the stage. They share dialogue roughly evenly, meaning that whenever an actor isn’t in the spotlight, they’re still hanging around beside it. That’s a punishing show—no nooks and crannies of production to hide in, hardly a break from speaking, and a Bible’s worth of lines to memorize.

Even so, the cast is strong. Veteran performer Pasquinelli is exceptionally compelling as Veronica, an artsy, strong-willed mom who fraysin a home that’s simply too mundane for her. Lazarovits is strong as well, playing a sophisticated but frustrated Annette who provides a more muted foil to Pasquinelli’s outrage.

There were occasional slips in the acting: even when delivering what were supposed to be confrontational lines, Lee and Powell could not escape a timid physicality that didn’t quite lean in to their conflict. In addition, some lines were clearly written with a pause in mind but nonetheless came tumbling out in a gawky, unnatural hurry. But presentation was good on the whole, and UT’s quiet ambition warrants high praise.

At some point in the show, each of the characters admits that they are having the worst day of their life. Yet every time they did, I was surprised: there is no way that was true. Everyone on stage, no matter how miserable they were, was having just a little too much fun.