The Museum of Contemporary Art’s immense new exhibition, Howardena Pindell: What Remains to be Seen, is hard to describe in several paragraphs. The exhibition, which opened last Saturday, is the first major survey of Howardena Pindell’s career and spans over 50 years of work by the black artist who is too frequently overlooked in the annals of art history.

While artists like Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein investigated the depths of flatness during the Pop Art craze of the 1960s, Pindell had already advanced to explorations of color, form, and structure in her works, testing the boundaries of rectangle-on-wall art. Born in Philadelphia in 1943, Pindell’s work brings together a variety of media into what has been called “figurative abstract expressionism.” Though her undergraduate training at Boston University had focused on figurative painting, she turned towards abstraction during graduate school at Yale University, and it was not until after 1979 that both forms would fuse.

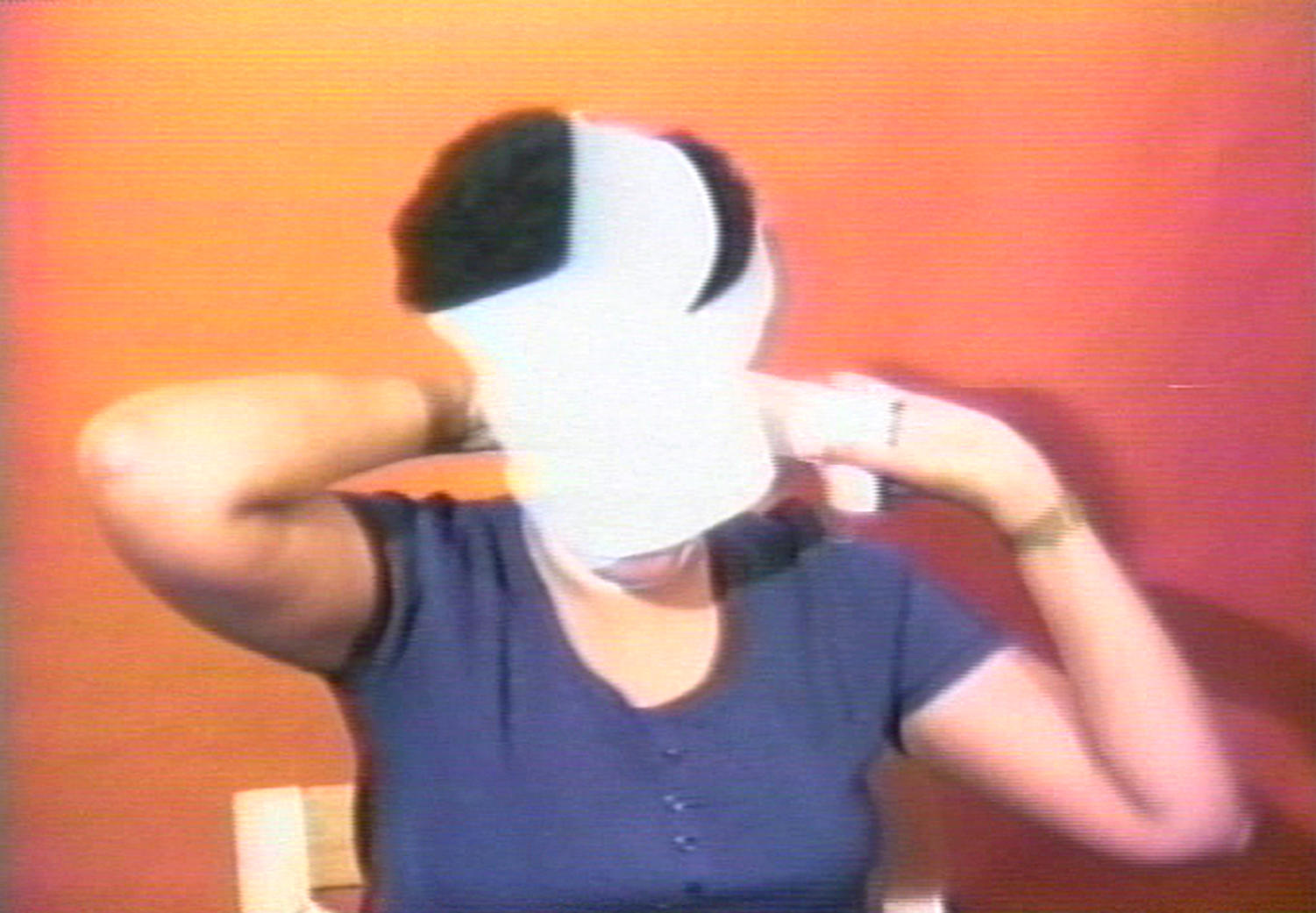

For a number of reasons, 1979 was a major inflection point in Pindell’s life and career, which the exhibition meticulously reflects. First, Pindell—a black woman—publicly opposed a show at Artists Space in New York entitled, “The N****R Drawings,” which featured charcoal drawings by a young, white, male artist named Donald Newman. Second, she made the major decision to leave her curatorial position at the Museum of Modern Art and begin teaching at Stony Brook University, where she still teaches today. Third, and perhaps most importantly, Pindell was severely injured in a traumatic car accident. She was trapped in front of numerous onlookers, who dared not approach her for fear that the gas tank of her car would explode. After the incident, Pindell suffered from severe short-term memory loss. Though she never abandoned her propensity for experimentation, she began reincorporating figuration into her previously developed techniques to probe topics like memory, culture, and social justice.

Appropriately, curators Naomi Beckwith of the MCA and Valerie Cassel Oliver of the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts have organized What Remains to be Seen into two sections, the first of which exhibits Pindell’s experimentation prior to 1979, and the second of which arranges Pindell’s work after 1979 based on her multidisciplinary approach as memoirist, activist, traveler, and scientist.

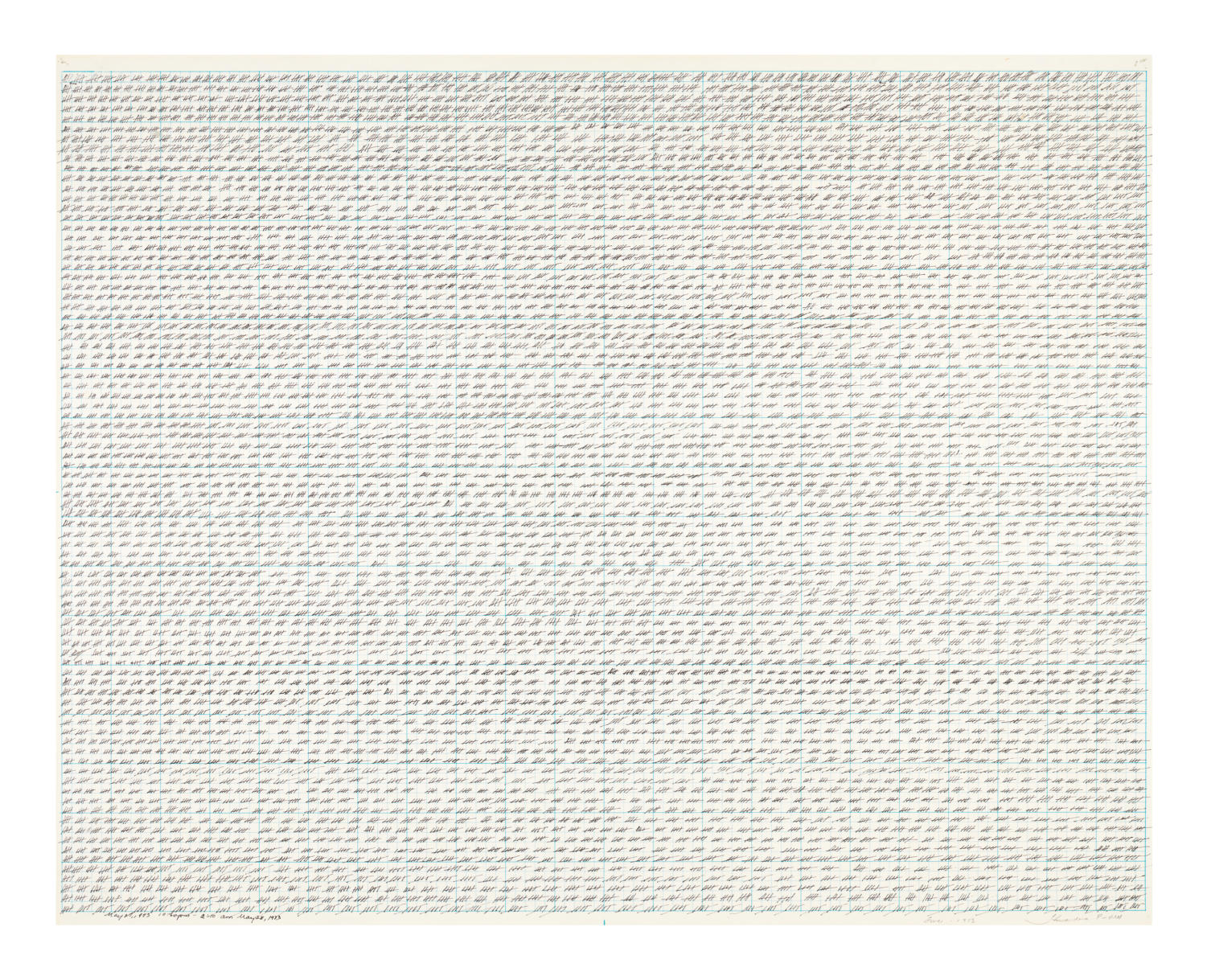

If the exhibition were limited to Pindell’s pre-1979 work, it would still be spectacular. Some of her earlier work was featured in the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Delirious: Art at the Limits of Reason 1950–1980 this fall, so it should come as no surprise that it explores themes of logic, order and chaos, and objectivity and subjectivity. In “Five” (1973), for example, Pindell writes sets of five tally marks in black ink, over and over again, on top of graph paper. The rigidity of the grid is confronted by the infinitude, obsessiveness, and vacuousness of the five black lines in endless repetition. Other works in this section feature rippling seas of colorful circles and texturally rich canvases covered in vibrantly colored chads—the perfectly circular paper detritus produced by a hole puncher.

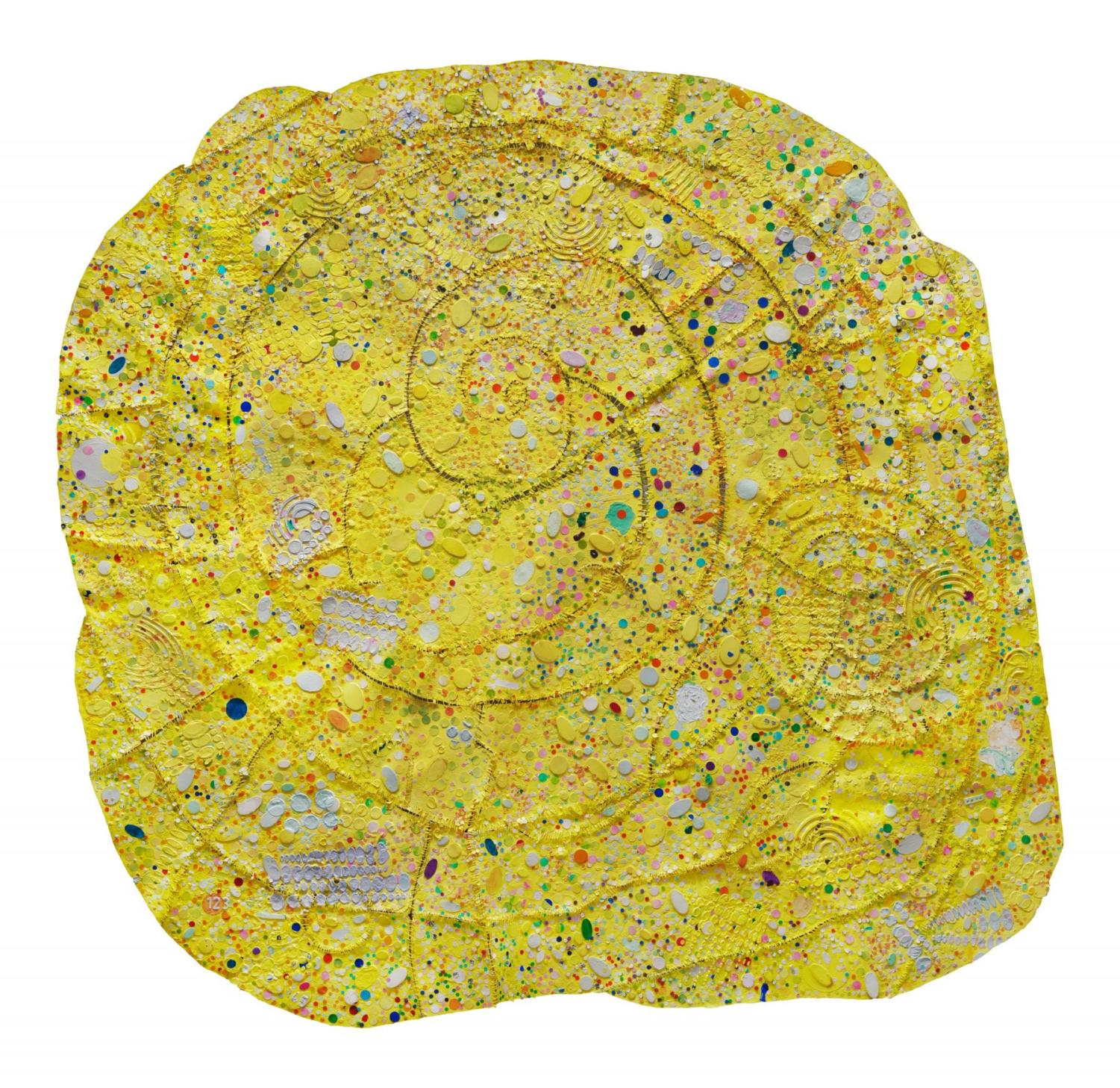

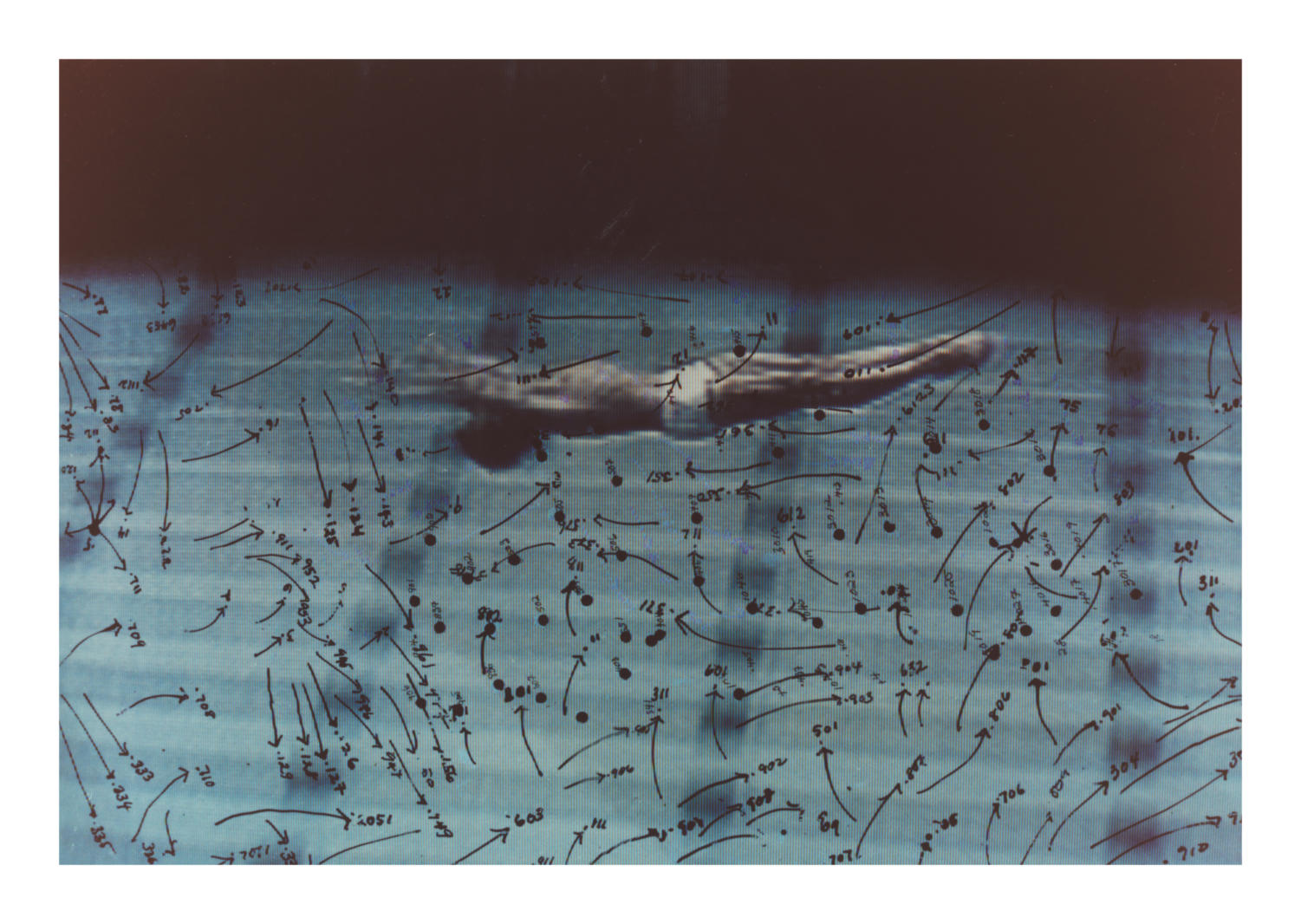

The second half of the exhibition is no less impressive. Sewing together canvases, which had previously been part of Pindell’s artistic practice, took on new meaning for her after the accident; while still making use of paint, glitter, and chads in these pieces, she also includes images of body parts, houses, and diners, as if she is stitching herself back together through canvases. In another series, Pindell cuts apart postcards of different landscapes and cultural icons and tapes them back together into one continuous, three-dimensional flow of images, all of which are fractured and ambiguous in meaning. One of the most stellar sections of the exhibition focuses on the role of activism in Pindell’s later art. She continues to apply collage to these works, sewing together ripped canvases, imitating stitch marks with parallel streaks of thick, monochromatic paint, and including words like “genocide” and “silence” floating amidst pertinent images. The exhibition concludes on a serene note by highlighting the collection of Pindell’s work that takes science as its subject matter. In “Nautilus 1” (2014–2015), Pindell rips apart a bright yellow canvas and sews it back together into a spiral. It is dotted with round, brightly colored shapes that suggest constellations. Pieces like these once again suggest the mystery and vastness of the universe, even as we know it in our everyday lives, in this case through objects like shells.

What really sets What Remains to be Seen apart is the scrupulous context included by the curators. Between the two halves of the exhibition, they have set up a “1979 room,” with magazine covers, album covers, advertisements from that year printed on the walls, and 1979 pop music playing from speakers. A timeline of Pindell’s life and of major global events is also included. Beyond this single room, the curators use wall text to carefully locate each work within its historical context. The exhibition thus takes special care to make sure it is accessible to a younger audience.

While the name “Howardena Pindell” may not immediately ring any bells, What Remains to be Seen is a promising step towards rectifying that.

“I look at my work as a kind of joyous play…a visual toy,” Pindell said in a press Q&A on Friday. What Remains to be Seen invites viewers to join Pindell in playing with her visual toys, and the invitation should not be turned down.

Howardena Pindell: What Remains to be Seen is on view at the Museum of Contemporary Art until May 20, 2018.