Since the opening of Max Palevsky Residential Commons in 2001, the University has seen a dramatic growth in new dormitory construction, with the opening of both Granville-Grossman and Campus North Residential Commons. Yet before Max P, the University hadn’t built any undergraduate housing for 40 years.

For most of its history, the University has taken a piecemeal approach to housing, relying on off-campus apartments and rarely having dormitory capacity for more than 60 percent of undergraduates. When new housing was needed, the University preferred to buy neighborhood buildings and refurbish them, as it did with Blackstone, Maclean, the Shoreland, and many other “satellite” dorms, than to undertake new construction projects.

In 2008, Dean of the College John Boyer presented “The Kind of University We Desire to Become,” a detailed report on the history of housing at UChicago. According to details provided in the report the University has considered major expansions of on-campus housing twice in its past.

In the late 1920s, University administrators proposed a massive undergraduate housing complex along 60th Street between Ellis and Woodlawn Avenues, but ultimately only saw Burton-Judson Courts built. Forty years later, the University announced a large housing complex on the site of Stagg Field, only to see its construction prevented by budget concerns and student upheavals in the late 1960s.

1928: The South Campus Complex

For the first several decades of its history, the University provided almost no student housing. As few as 20 percent of students lived on campus, and often there were more students living in the numerous fraternity houses than in dormitories.

In fact, until at least the 1950s, the University was in large part a commuter school, with around 40 percent of students living at home while attending. Many of the dormitories that did exist, including Snell, Hitchcock, Gates-Blake, Goodspeed, Foster, and Green, were shared between undergraduates and graduate students.

When Ernest Burton became the University’s third president in 1923, he conceived an ambitious plan to change that. Inspired by his experiences touring Oxford, Burton imagined turning the entire area south of the Midway into a set of integrated “colleges” for undergraduates.

His plan also involved a restructuring of the undergraduate curriculum, somewhat similar to the Core later adopted under President Robert Maynard Hutchins in the 1930s. Under this plan, undergraduates would take a two-year general education curriculum followed by two years of more specialized learning, which would be more integrated with the University’s graduate divisions.

Burton’s plan was inspired by contemporary developments at Yale. Yale’s president, James Angell, was a University of Chicago psychology professor from 1895 to 1919 and expected to become University president after serving as acting president from 1918 to 1919. But when then-president and political science professor Harry Pratt Judson refused to step aside, Angell left and eventually moved to Yale in 1921.

Starting in 1925, Angell implemented a residential college model at Yale similar to the one that Burton proposed around the same time for UChicago. Harkness Quadrangle, the product of Angell’s effort, became a model for UChicago’s proposed college buildings.

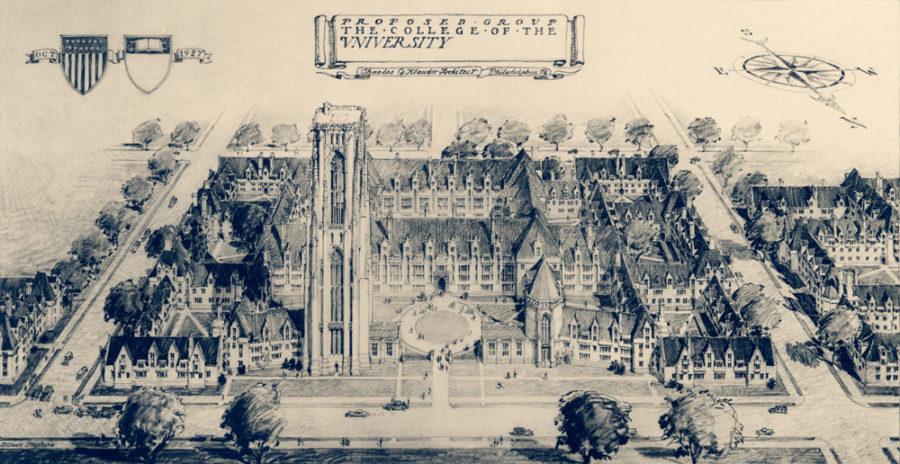

In 1925, Burton died and was succeeded as president by Max Mason, who shared a similar vision. Initially, the plan went ahead under the direction of Vice President Frederic Woodward. In 1927, architect Charles Klauder, who had built dormitories at Princeton and Cornell, was commissioned to design the South Campus complex.

Under Klauder’s plan, the entire area between Ellis and Woodlawn would have become a mixed-use undergraduate college, with a 44,000-square-foot library, classroom space, and the capacity to house 2,000 students.

A version of the plan scaled down to focus on student housing received approval in 1928. Its total cost was $5 million, of which trustee Julius Rosenwald pledged $2 million and the University fronted the rest. In this plan, the University would build two men’s halls along Ellis, two women’s dorms to their east, and an arts building on the other side of Woodlawn. In total, the complex could house between 1,400 and 1,600 students.

However, Woodward’s plan for the Colleges met stiff resistance from faculty who felt they detracted from the University’s research-oriented mission. Led by professors William Dodd and Charles Merriam, they worried the University would end up prioritizing less academically serious undergraduates over more serious graduates, and preferred to shift focus away from the College, even to the point of abolishing it.

“Let undergraduate loafers go anywhere else, especially to Yale and Harvard where swaggy manners and curious accents can be learned easily,” Dodd would later say in 1934, according to Boyer’s report. “Real students should be appealed to and then genuine offerings be easily available. This would mean many graduate students.”

Even worse for Woodward, both Dodd and Merriam were prominent members of the search committee to find a new president. Mason had resigned in 1928 and Woodward, now acting president, was widely favored for the job, but their opposition torpedoed his chances.

Instead, the board opted for a younger man, then-dean of Yale Law School Robert Maynard Hutchins.

Hutchins, though his own plans for undergraduate education would eventually turn into the Core, had little interest in the dream of a residential college, and did little to support it. Burton-Judson Courts, the only one of four dormitories slated to be built that was actually built, was completed in 1931. The other three were delayed and eventually killed by a combination of faculty opposition and the economic strain of the Great Depression.

1964: The Blum Plan

In 1960, the University implemented a strict residency requirement in which women would have to live on campus for four years and men for two. But the plan was hampered by the perceived low quality of campus housing at the time.

Woodward Court, a women’s dormitory on the current site of the Booth School, opened in 1956, and Pierce Tower opened for men in 1960. Both had very small rooms and at one point the dean of Yale Law School wrote to complain about his son’s living conditions. In 1964, the residency requirements were effectively rescinded.

In a letter at the time, University Dean of Students Warner Wick lamented campus living conditions.

“In any case, we are not competitive [in housing] with the colleges we like to think of ourselves as competing with,” Wick said according to Boyer’s report. “Talk of our ‘residential college’ is a big laugh, and the world is hearing about it.”

In response, University Provost Edward Levi appointed a faculty committee chaired by law professor Walter Blum to deal with the issue.

Blum’s report, completed in 1965, argued for a broad expansion of on-campus housing, including possible construction on the current site of Granville-Grossman Residential Commons and an additional tower near Pierce. However, the report’s boldest proposal was for a large student village, to be built on the present site of Stagg Field, including shops and an athletic facility.

In addition, it questioned the quality of recently built dormitories, citing long-standing and widely shared concerns over their living conditions.

“Unfortunately, the last two residences built by the University—Pierce Tower and Woodward Courts—suffer badly in comparison with housing built by other schools with which the University competes for students,” the Blum Papers said.

Spurred by the report, the University announced plans for the North Quadrangle, a planned complex on the site proposed by Blum. It would cost $23.8 million, house 900 students, and include other amenities such as arts and athletics facilities.

But the plan was soon shelved in favor of other priorities. Student protests played a role: Hundreds of students occupied Levi Hall for two weeks in 1969, leading to 42 expulsions. In response, the College significantly reduced the size of its incoming class, eliminating some of the incentive to build new housing.

In addition, the University needed funding for other ambitious campus projects, including the construction of Regenstein Library, which opened in 1970. As a result, Blum’s plan, like Woodward’s, never took off.

Today

The expansion in housing since the opening of Max Palevsky has already added over 2,000 new beds for College students, as large as any of the projects considered in the past, although not limited to one location.

The College’s enrollment has grown from 4,103 students in 2003 to 6,150 students today, creating a need for much more on-campus housing. In addition, under Boyer the College has set a goal of being able to house at least 70 percent of undergraduates on campus.

In 2009, the college opened Renee Granville-Grossman Residential Commons, then known as South Campus. Pierce Tower, famous for its exploding toilets toward the end of its existence, was demolished in 2013, and students were relocated to International House and New Graduate Residence Hall. New Grad, along with three other undergraduate residence halls, were later made defunct with the construction of Campus North Residential Commons in 2016.

The College’s newly-proposed residence hall, Woodlawn Residential Commons, will house 1,200 students and is slated to break ground this summer.