“YERKES BREAKS INTO SOCIETY—Street-Car Boss Uses Telescope as a Key to the Temple Door—AND IT FITS PERFECTLY,” the Chicago Evening Journal exclaimed when Charles Yerkes financed UChicago’s Yerkes Observatory in 1892. More than 125 years later, the University plans on withdrawing from the observatory—and the observatory, once the site of experimentation and innovation, could be closing its doors. But for many years, the “key” fit perfectly.

The Maroon looks back on Yerkes’s long history, from its storied past to its uncertain present.

A Star-Studded Beginning

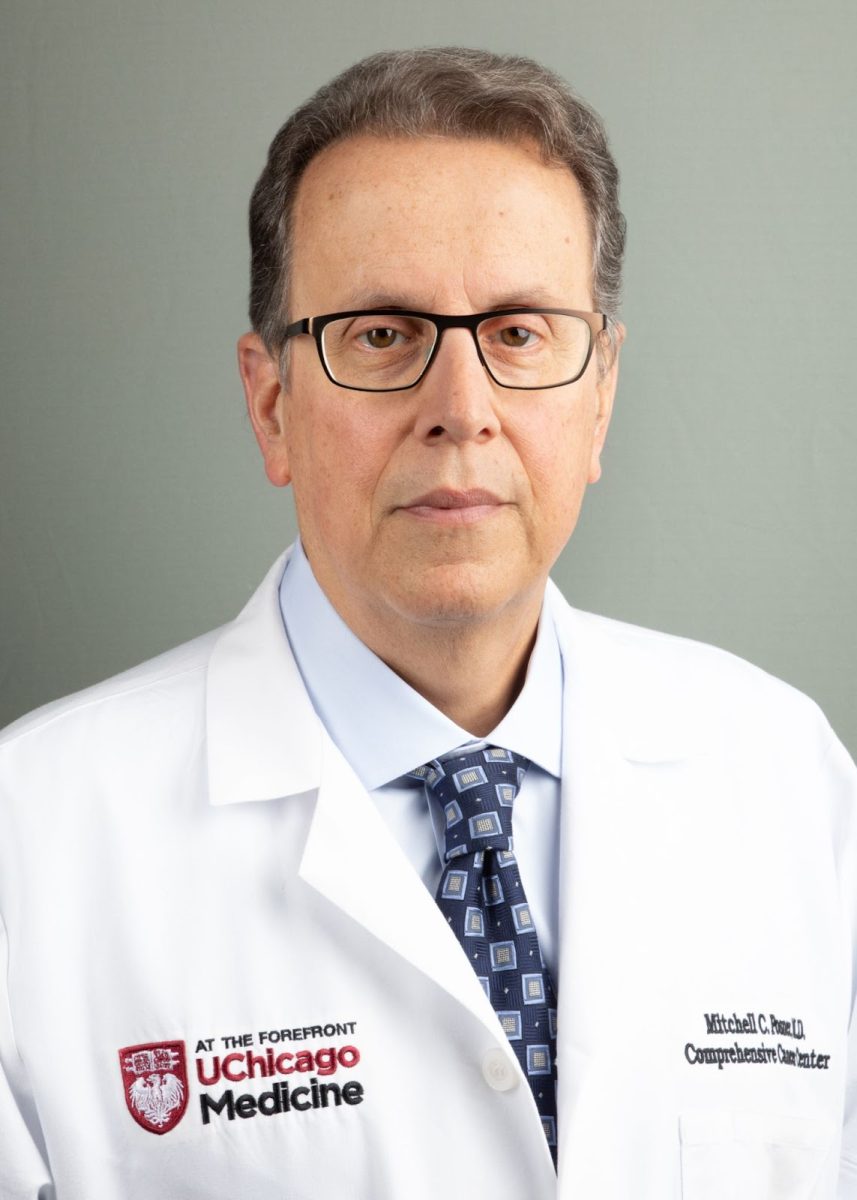

The observatory’s story begins in July 1892, when William Rainey Harper, the University’s first president, hired George Ellery Hale as an associate professor in astrophysics. At the time, Hale’s family owned their own observatory in Kenwood, which then became part of the University.

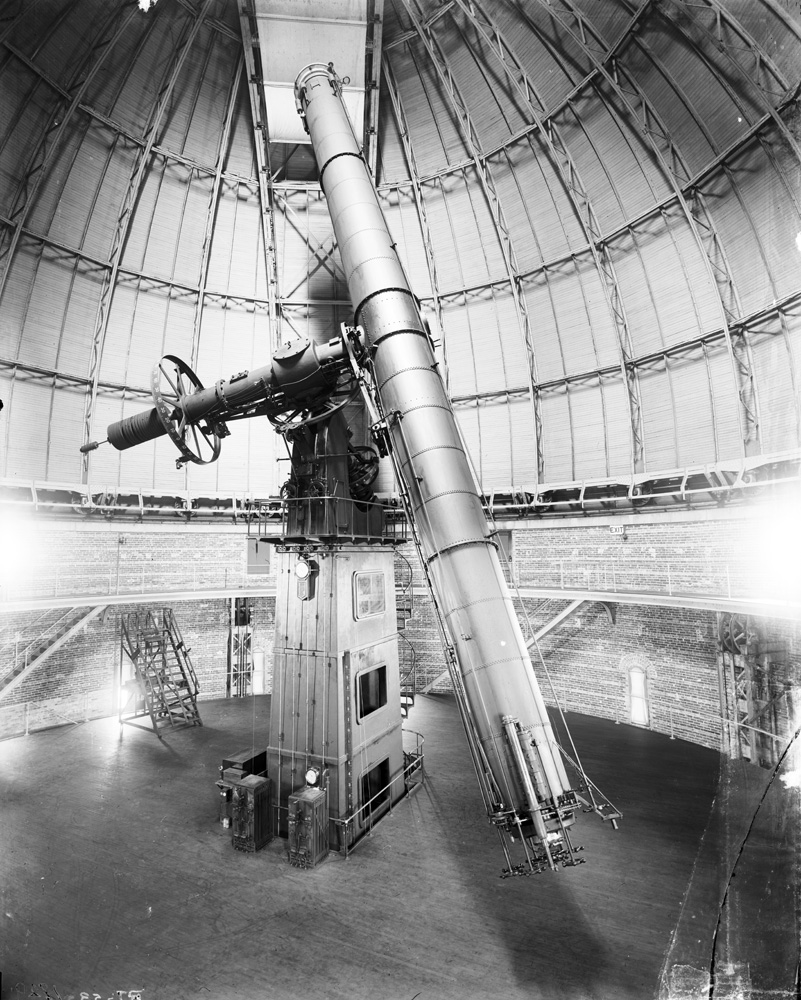

During a scientific conference that September, Hale heard from another researcher about a set of glass optical disks for telescopes—40 inches each in diameter—that had been recently crafted for the University of Southern California. The lenses’ diameter and thinness allowed them to take in more light than other telescopes and to give astronomers a sharper, more vivid look at the cosmos.

But USC was unable to finance the lenses, so they remained on the market.

At the time the largest refracting telescope in the world was only 36 inches in diameter, so Hale and Harper became intrigued with the prospect of buying the 40-inch diameter lenses. The next month they set up a meeting with Charles Yerkes, a financier who helped fund Chicago’s mass transit.

Yerkes agreed to provide $500,000 for the telescope and a new observatory, according to a New York Times article announcing the gift. The observatory was set to be built by New York–based construction firm Warner and Swasey of New York City, and would bear Yerkes’s name.

The telescope itself came into the public eye the very next year, when parts of it were displayed at the World’s Columbian Exhibition in Chicago in May 1893.

In an 1897 book he authored about the observatory, Hale explained why Yerkes Observatory could not be located in Chicago.

“Some of the other researches demand a dark sky and great transparency of the atmosphere, while for still others the principal requisite is complete protection of the instruments from vibrations of any kind,” he wrote.

According to Hale, the University’s trustees understood that the research intended to be done at Yerkes could not be done on campus, or even in Chicago. Hale wrote that several towns in Illinois, Wisconsin, and even California had expressed interest in hosting Yerkes as soon as word got out about the observatory.

After reviewing the sites, Hale and other researchers decided on a site next to Lake Geneva, Wisconsin, near the town of Williams Bay.

“The region is one where the mean annual cloudiness is low for this part of the United States, there is but little dust, and the nights of the best observing months are usually calm,” Hale wrote of the decision.

Construction on the site began in April 1885 and concluded in May 1887, according to Yerkes’s first annual director’s report, which was written by Hale in 1898.

The observatory was designed by Henry Ives Cobb. Frederick Law Olmsted, whose other notable projects include Midway Plaisance, Jackson Park, and Botany Pond on campus, designed the grounds.

Equipment from the Kenwood observatory was brought over to Yerkes as well.

Hale described the classes and research taking place at Yerkes during its first year, including classes on astronomical spectroscopy (measuring radiation from stars) and celestial photometry (measuring the brightness of stellar radiation).

Researchers also took solar and star photos at the observatory with the help of the telescope, “in spite of the fact that the forty-inch telescope is not intended for photographic work,” Hale wrote in the report.

Hale remained at Yerkes until 1904, when he left for the Mount Wilson Solar Observatory he had founded in California.

A Stellar Site

Edwin Frost, Yerkes’ second director, described some of Yerkes’ early accomplishments in a retrospective published in 1923.

For example, the article notes that astronomer Sherburne Burnham studied double stars, or star pairs that seem to be near each other when viewed, and published related research in 1904.

Just four years earlier, the observatory successfully photographed stars using the telescope. Astronomer Frank Schlesinger used this to measure the distance of stars from Earth.

Other significant explorations included the measuring of heat from the stars in 1898 and 1900, and an experiment about the earth’s rigidity in 1913. (A Journal of Geology article explains that the experiment explored the question of whether what lies beneath the surface of the earth is rigid or fluid.)

“During the past twenty years, the average number of hours per year during which the 40-inch telescope could be used at night has been nearly 1,700,” Frost wrote.

Frost also expressed his wish that the observatory had done more since its founding, even as he spoke of its experiments, equipment acquisitions (including another telescope in 1906), and published papers.

“We frankly admit that we have accomplished in these twenty-five years far less than we could wish…. The observatory has no spectacular achievements to record, but it has been the policy to carry on a program of observations which would be certain to be useful, rather than to spend much time in attempting to make discoveries which might not be realized,” he wrote.

During Frost’s tenure, Edwin Hubble, who went on to discover galaxies beyond the Milky Way, and Otto Struve, who discovered the existence of hydrogen in space, both conducted research at Yerkes.

Struve took over as director of Yerkes in 1932, and led Yerkes through a deal with the University of Texas to open the McDonald Observatory that year in western Texas. Yerkes and the University would run operations at McDonald until 1963, when an astronomer from the University of Texas took it over.

Struve, a Russian immigrant to the United States, joined Yerkes in 1921 and spent the following years revitalizing and guiding the observatory during World War II.

One major innovation pioneered during his tenure was the Yerkes Spectral Classification. Created by researchers William Morgan, Philip Keenan, and Edith Kellman, this system categorizes stars into six groups by luminosity.

Thanks to innovations in telescoping technology, the observatory’s refracting telescope, the original raison d'être of the site, became obsolete as the 20th century continued. Newer telescopes with mirrors worked more effectively and were built in sites that had less light pollution.

In the 1960s, the astronomy department moved from Wisconsin to Hyde Park, in order to bring the department onto campus, which left Yerkes without any academic department on its premises.

The observatory continued to be used for educational, research, and outreach purposes, and in the past two decades has been a site of several astrophysics discoveries.

In the early 2000s, researchers at Yerkes began developing the High-resolution Airborne Widebandwidth Camera (HAWC), an advanced infrared camera for NASA’s Stratospheric Observatory for Infrared Astronomy (SOFIA). SOFIA is a modified airplane equipped with a telescope for making astronomical observations. This camera was built to assist with the study of star formation and the Milky Way’s magnetic fields.

The first version of HAWC was completed in 2013. Its latest iteration, HAWC+, is beginning to make observations this year, according to the Universities Space Research Association.

In June 2007, Yerkes was linked up to the University of North Carolina’s Skynet Robotic Telescope Network. This allowed researchers at Yerkes to access feeds from telescopes around the world, while sharing a feed from Yerkes’ telescopes online for the public to view.

Yerkes’ initiatives aren’t limited to adult researchers. A $2.5 million grant from the National Science Foundation in 2017 supported the launch of Innovators Developing Accessible Tools for Astronomy (IDATA).

According to the Yerkes Educational Outreach website, “IDATA is a three year project…that will engage a group high school age students, their teachers, professional astronomers, software engineers, and design experts in the user-centered design process of data analysis software for astronomy.”

The program aims to produce astronomy software and aids for the visually impaired, with design help from students from around the country.

As of earlier this month, the future of IDATA at Yerkes remained uncertain, but researchers involved have expressed hopes that the program will continue through the project’s official conclusion in October 2019.

A Cosmic Sale

The University had tried to cut ties with Yerkes at least once in the past, over a decade before its current decision to pull out.

By June 2005, the University was seriously beginning to explore the possibility of selling Yerkes and its land.

A bidding war erupted over Yerkes and its land in October 2005. Aurora University, a liberal arts college with a campus adjacent to the observatory, and development company Mirabeau both submitted proposals for the future of the site.

The University required both groups in their proposals to preserve the observatory building itself.

Aurora bid $4.5 million, and proposed making the observatory into a facility for its own campus. Mirabeau bid $10 million and planned on creating a foundation to run the observatory which would include UChicago representatives; the company also indicated plans to build houses and a hotel on the site.

But by February 2006, the future of the site remained unclear.

The primary roadblock was environmental: both proposals included development that would include a sewer extension, which would be prohibited by the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources out of fears of compromised water quality.

In October 2006, Mirabeau won the bidding war and gained the rights to the land, with the condition that the observatory itself be given to Williams Bay Village.

A University news release lauded the deal as helping “preserve the historic astronomical observatory and 30 acres surrounding it,” along with providing more funding for research and outreach.

The village itself opposed the deal, and showed reluctance to adjust zoning laws and zoned areas to allow Mirabeau to move forward. As a result, Mirabeau withdrew its bid in June 2007, leaving the site still in the University’s hands.

A Horoscope for Yerkes

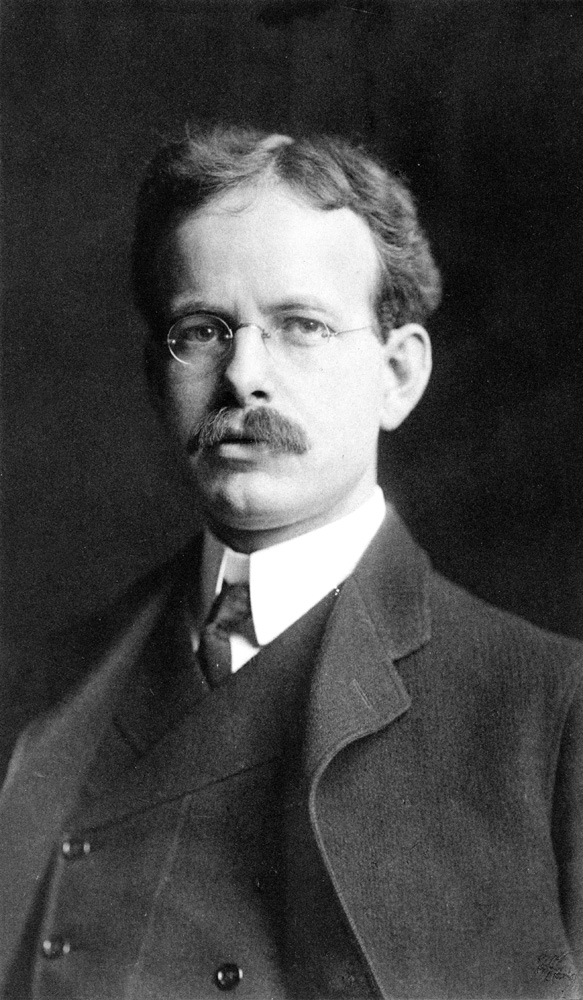

Doyal Harper, a professor in the department of astronomy and astrophysics, currently directs the observatory.

Yerkes currently hosts various summer camps and public events. The site can also be booked for special tours, corporate events, and weddings.

The observatory’s future remains in doubt as the University’s withdrawal approaches.

During a March 19 meeting, as reported by the Lake Geneva Regional News, residents of Williams Bay Village pressed University representatives on what will happen to Yerkes, and whether it will be preserved.

University executive vice president David Fithian told residents that the observatory will not be demolished, and that maintenance staff will remain at Yerkes even if no plans are made by October about the future.

Fithian and Dean of the Physical Sciences Division Edward Kolb said the University does not plan on attempting to sell the site again, or even to move the telescope and other equipment.

A March editorial in the same paper exhorted residents of the area to make their voices heard: “There will certainly be more public meetings in the future. We encourage everyone who cares about Yerkes Observatory, and the future of the land and building, to attend those meetings… The ‘ultimate disposition’ of the building and real estate will likely take some time to decide. If that’s the case, and if you care about the future of the facility, prepare to stay engaged for a long time.”

Before the university withdraws, Yerkes is reflecting back on its beginnings.

This summer, it will host the Starlight Festival, a two-day astronomy festival featuring speakers, scientific demonstrations, and tours of the facility. The festival will commemorate the 150th anniversary of Hale’s birthday.

Sophie Roth contributed reporting. Third-year Priya Lingutla, former history intern at Yerkes, and Dan Koehler, Director of Tours and Special Programs at Yerkes and Co-Chair of Starlight Festival 2018, provided information and research.