Heinrich von Kleist’s The Broken Jug is a dark comedy that follows the stories of “Adam,” “Eve,” and a trial for a beloved and mysteriously broken jug belonging to Eve’s mother, Frau Marthe. Frau Marthe blames Ruprecht, Eve’s fiancé, but it soon becomes clear that the real culprit was Adam, the village judge.

Last weekend, TAPS and UChicago Arts presented a production of the play, directed by graduate student Pirachula Chulanon, based on a translation by Chulanon, Ella Wilhelm, Ena Gojak, and Stephen Cunniff. The original play was first performed in 1808, but this edition was anything but old-fashioned. The fascinating yet unnerving show featured puppetry, singing, and lots of food.

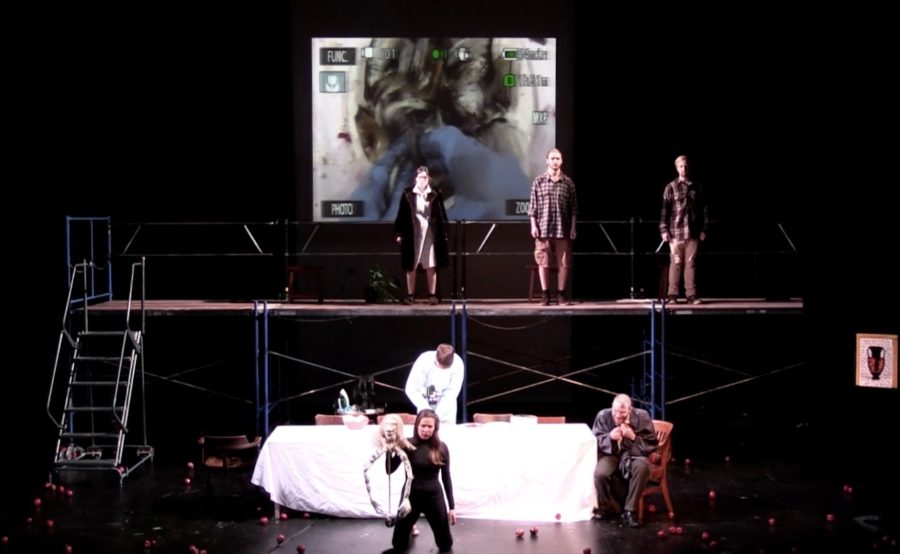

Typical of black box theater (in which a play is performed in a square space with a flat floor and black walls), this version of The Broken Jug featured a minimal set and costumes. Notably, the set was littered with apples, no doubt a reference to the Garden of Eden. Indeed, there were many set and costume choices designed to create a surreal, disconcerting atmosphere. Eve was played by a simple, colorless puppet made of rope, muslin, masking tape, and twine, giving her the appearance of a strange, primitive ghost. Judge Adam’s wig, an important piece of evidence in the trial, is represented by a large, shocking orange costume wig, rather than the traditional white judge’s wig.

The bleak set emphasizes the strange mannerisms of the characters and the story at hand, much of which took place in the past and is relayed through monologue. The simplicity and modernity of certain props, such as the apples and the wig, force the audience to question its purpose in the story. The result, however, is a bit of a visual assault against the simple set. Indeed, Chulanon’s use of subliminal messaging is so successful that one feels they are not comprehending everything that is taking place.

In addition to set and costume choices, ominously deadpan acting and eerily repeated phrases—sometimes spoken in unison by the whole cast—created an unnatural dissonance. The most peculiar aspect of the play, however, occurred when Adam’s assistant picks apart and “cooks” rotten food for the duration of the trial. The food and his hands are magnified, the spectacle displayed extra-large on a screen on the set’s back curtain. On the whole, the play was at times shockingly offbeat, at others dryly amusing. It was, one might say, a lot to digest.

To pull off such an ambitious interpretation of what is already a rich story, one must have a talented cast. Stephen Cunniff gave a standout performance as Adam, whom he portrayed with equal parts whimsy and hair-raising murkiness. In one scene, he begins the trial at hand under the watchful eye of Walter, the state inspector, by informally berating Frau Marthe and forcing her to introduce herself, although he already knows her. When prompted to follow regular court proceedings, he changes tune and explains that, of course, he knows how they do things in the city, and is versed in their customs. Cunniff’s ability to so clearly reveal his character’s deception is eerie but hilarious. Sharvari Sastry, who played Walter, delivered another strong performance. In the first act of the show, she is skeptical and sassy, clearly fed up with the illegitimate Judge Adam. Her dialogue with the Judge is one of the most amusing aspects of the show, due in large part to her spot-on comedic timing and delivery.

TAPS’s production of The Broken Jug is akin to a strange dream. While watching, one is never sure what plot twist or turn might come next. Leaving the dark theater and emerging into the well-lit lobby of the Logan Center felt like waking up. As I walked away from the show, its plot, which had been difficult to grasp amid the sensory overload of the many unconventional set and directorial choices, slowly surfaced. At its core, the play mocks the judicial system by revealing the transitory and fickle nature of blame and culpability—and by examining our propensity to condemn the innocent, like Eve, for the crimes of the guilty, like Adam.