A jury has sided with a former University of Chicago Police Department (UCPD) commander, Milton Owens, who filed suit in 2015, alleging he was wrongly fired. The University is now contesting the jury’s decision.

Owens claims he was made a “scapegoat” by the University following a high-profile incident in February 2013 when a plainclothes officer under his command disguised herself as a protester to get intel on the activists who were pushing for a trauma center.

Detective Janelle Marcellis, who is still employed by the UCPD, carried a protest sign and marched alongside activists. Owens, as commander, was found responsible for UCPD’s conduct; Marcellis was let off with a warning for exercising “poor judgment.” She was instructed to be in plain clothes, but she took it upon herself to carry a sign and wear a sticker.

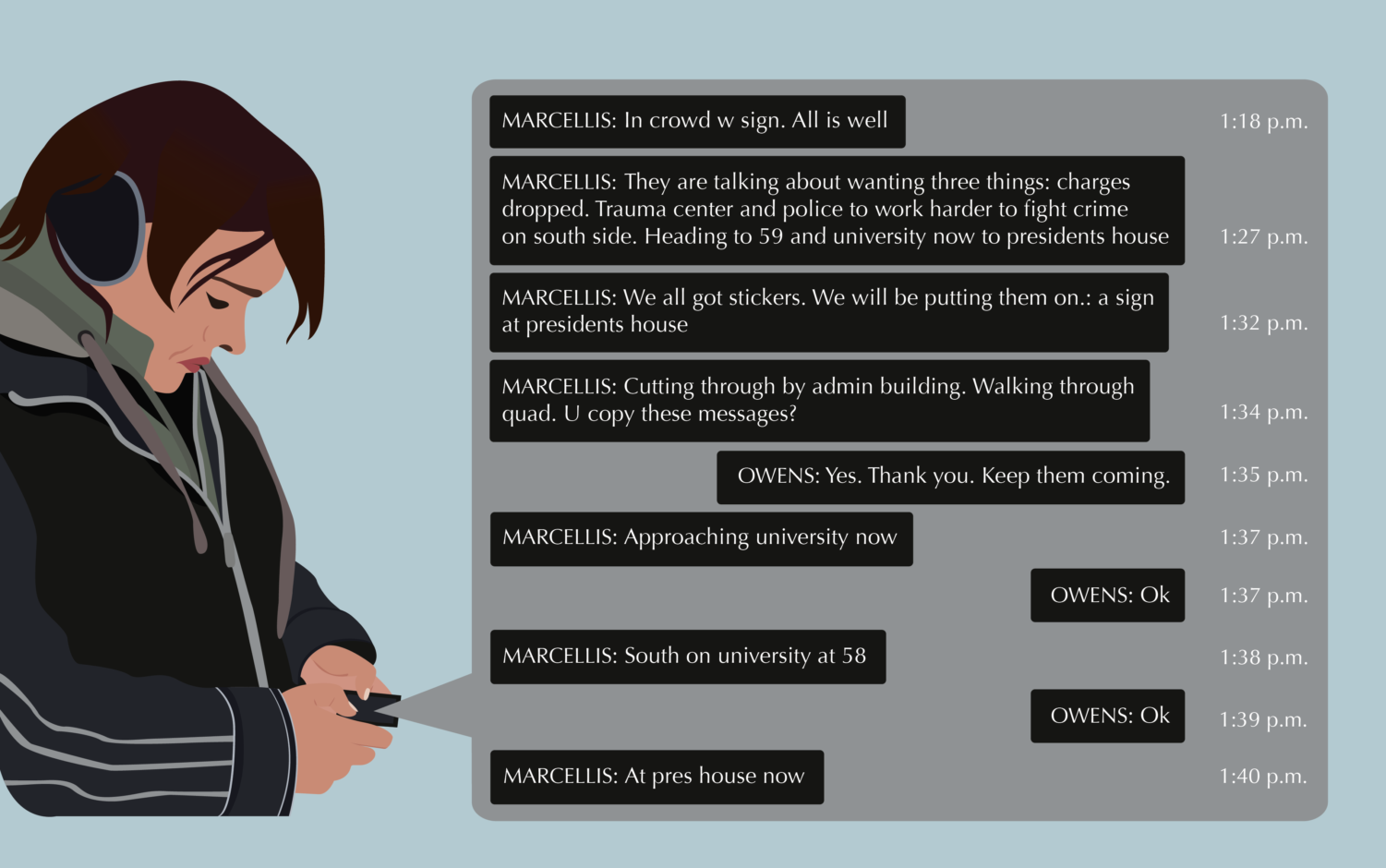

Shortly after the UCPD infiltrated the protest, a source provided photos of Marcellis to The Maroon, including incriminating pictures of her cell phone that showed texts to Owens: “In crowd w[ith] sign. All is well,” one read.

After The Maroon published an article detailing Marcellis’s actions, President Robert Zimmer issued a statement condemning the infiltration of the protest. The University hired a law firm, Schiff Hardin, to review the events. Meanwhile, the UCPD launched its own investigation, led by department official Eric Heath, who is now the University’s Associate Vice President for Safety & Security.

Owens was dismissed from his job in March 2013 under a rule forbidding any action that “brings discredit upon the department.”

Owens sued the University alleging he was wrongfully terminated, claiming higher leadership was actually responsible for the protest infiltration. Owens thinks the blame fell on him because he was not part of an “old boys’ club” of UCPD officials from elite universities, who all knew each other.

Heath’s report and the report published by Schiff Hardin said that Owens defied the UCPD leadership’s plan by giving Marcellis orders to “blend in” with the protesters. His instructions to Marcellis are referred to as a “counter-order.”

Yet, court documents obtained by The Maroon suggest that, rather than acting unilaterally to defy leadership, Owens was following orders of which he was initially skeptical. Before the protest, Owens had questioned why they were using plainclothes officers at all, voicing his doubts to then-Chief of Police Marlon Lynch.

The defense claims that such extreme police measures were taken in part because they had intelligence that gang-affiliated groups who wanted to target Chicago Police Department (CPD) officers might join the protest, which proved not to be true. The UCPD was also on edge because the trauma center protests had brought a new intensity of activism to campus.

Owens’s lawsuit brought charges against the University, Lynch, Zimmer, Assistant Chief Gloria Graham, and Deputy Chief Kevin Booker, with allegations of fraud, breach of contract, intentional and reckless infliction of emotional distress, and intentional and reckless spoliation of evidence.

The suit went to trial in January. In March, the jury found in favor of Owens on his claim of infliction of emotional distress. Following this finding, the University and Booker, who is now Chief of Police at the University of Illinois at Chicago Police Department, jointly owe $150,000 in damages to Owens. The University has filed a motion for judgment notwithstanding the verdict, asking Cook County Circuit Court Judge Joan Powell to overrule the jury’s finding in favor of Owens.

In a statement, a University spokesperson said the administration respects the jury’s verdict, but believes it was unsupported by the facts and the law. The University will challenge the outcome via post-trial motions, and the spokesperson said they could potentially appeal the case.

UCPD’s protest plan: 35 cops

A month before the infiltration incident, the UCPD had come under fire for its handling of another trauma center protest, where four protesters were arrested. A video showed officers forcefully restraining protesters and bringing them to the ground.

There was no investigation of the officers involved, the University said, because it saw no misconduct and there were no complaints.

Owens was off duty during the January 27 protest, but was called in as the situation escalated. Owens would later describe being shocked at the chaotic scene and at officers’ violations of protocols, including neglecting evidence collection standards such as photographing injuries and interviewing witnesses.

“When I arrived there, what I discovered is that there were people under arrest that had not been Mirandized, that juveniles hadn't been processed properly, that [officers] who had arrested people were gone and [we] did not know who arrested this person under arrest,” he told The Maroon.

According to Owens, when he was brought on in 2009, the UCPD was acting more like a “security agency” than a full-fledged police department. Owens was originally recruited from the CPD when the UCPD was making a broad push to develop more consistent standards, including a set of General Orders (the rules governing a police department), as it strived for Commission on Accreditation for Law Enforcement Agencies (CALEA) accreditation, which it got in 2014. He said it felt good, at the time, to be at the “ground floor,” building a robust operation.

This was part of the backdrop to the department’s decision, when command staff learned of another trauma center protest scheduled for February 23, to draw up a comprehensive plan to monitor, videotape, and “gather intelligence” from protesters.

Owens stressed that the UCPD developed its plan for the February 23 protest as a direct response to the negative press in January. Normally, Incident Command System (ICS) plans are reserved for dignitaries’ visits and other high-profile events. But when activists posted flyers advertising the march, command staff decided to use ICS protocols to plan for the event.

Although he was part of senior department leadership, Owens said he was not included in talks about the development of the ICS plan. At the time, Owens was deputy chief of Investigative Services, and he was scheduled for promotion March 1.

At a February 18 command staff meeting, Booker delivered a PowerPoint presentation of the ICS plan. It was at this meeting that Owens first learned the department intended to use plainclothes officers. Owens was assigned to monitor 32–35 people on the day of the trauma center protest. Of those officers, a unit of three detectives—Janelle Marcellis, Eric James, and Carlton Hughes — were instructed to wear plainclothes.

Their tasks were to “gather intelligence” and videotape the protest.

Owens never wanted Marcellis in plainclothes

Court documents from both the plaintiff and defendants agree that when Booker presented the plan at the February 18 meeting, Owens suggested that Marcellis, James, and Hughes be in uniform and act as an “arrest processing team.” However, Graham insisted that the detectives be in plainclothes.

Owens was concerned because, at the time, the UCPD had no policies and procedures regarding the use of undercover operations.

The assignment raised “red flags” for Owens because the detectives had less than two or three years on the job and had never been trained in dealing with protests or demonstrations, Owens testified.

At the conclusion of the meeting, Owens restated his concerns to Booker, in the presence of Lynch, again asking if he could have his officers in uniform rather than in plainclothes.

According to documents, including the defendants’ motion for summary judgment, Booker told Owens to stick with the ICS plan for plainclothes officers, saying, “Gloria [Graham] wants it that way.”

In the same conversation, for which Chief Lynch and Commander Celeste D’Addabbo were also present, Owens asked Booker to clarify what was meant by the vague instruction in the ICS plan to “gather intelligence.” Booker told Owens his officers should “mingle and join in” with the protesters, according to Owens and to the University and Booker’s motion for judgment notwithstanding verdict.

In his statement for the UCPD investigation, Booker told Heath uniformed officers can agitate protesters, whereas “a plainclothes officer doesn’t make the crowd as hyper or aggressive.”

Owens communicated the plainclothes instructions to Marcellis, but she took it a step further by actively participating in the protest with the sign and the tape.

“Based on [Owens’] instruction, Det. Marcellis stated as she entered the protest group, she voluntarily took a sign and stickers in an effort to either “blend in” or “be a protestor” [sic]. Det. Marcellis’ voluntary decision to actively engage in the protest by taking a sign and stickers ultimately resulted in the embarrassment and discredit of the University of Chicago and its Police Department,” Heath’s report reads.

Lynch met personally with protest group leaders on the day before the event to coordinate plans and identify liaisons, but did not inform the activists that there would be plainclothes officers.

In court proceedings, officers cited intelligence that gang-affiliated groups might join the protest as one reason why UCPD took the unusual measure of developing an ICS plan for the protest. In testimony, the defendants said they had thought the date of the protest was selected because it was the anniversary of a CPD shooting of a civilian.

“There was intel out there that they wanted retaliation on CPD,” Booker told Heath in his statement for the internal investigation.

Owens’s attorney, Alexander Vroustouris, doesn’t buy that explanation.

“Booker, when the shit hit the fan, had to justify why they had an ICS plan. The real reason is, they didn’t want to screw up like they did on January 27. But they can’t say that because that sounds terrible. So one of the ways around it is to say ‘we got some intelligence that there might be some violence,’” Owens told The Maroon.

They all thought it was funny

On the day of the protest, which was organized by local activist groups including Fearless Leading by the Youth (FLY) and Students for Health Equity (SHE), Marcellis entered the crowd and marched alongside activists, carrying a sign and wearing a sticker over her mouth that read “TRAUMA CENTER NOW.” Both were handed to her by an activist who was distributing protest materials.

In Heath’s initial investigation—and while testifying on the stand—Marcellis admitted that she took the sign and sticker on her own accord, but she insisted that she did so because Owens had instructed her to “be with the protesters.” Owens did not dispute that he directed Marcellis to gather intelligence by blending in, but testified that he was merely relaying the ICS plan as it was communicated to him by Booker.

During the protest, Owens texted Marcellis that he copied her updates, and he told her to “keep them coming” in a message sent 17 minutes after she said she was holding a sign.

In testimony, however, Owens claimed that he did not know Marcellis had taken the sign and stickers until after the protest was over. He said he kept his phone in his pocket for most of the time, to keep his battery charged in the extreme cold, and he said he did not read all of Marcellis’s messages due to the weather.

Either way, it appears that Owens was comfortable with the protest infiltration once he had clarity that it was what leadership wanted. In her statement to Heath, Marcellis said that Owens had directed her to participate in the demonstration “as a protester.”

“When I got back into the car with Deputy Chief Owens he said, ‘great job,’” Marcellis’s statement reads. “He knew I had the sign, he knew exactly what I was doing because I told him and he even said that this was how we are going to handle protests from now on. He said, ‘I think this is excellent, this is what we did at CPD.’”

After the protest, Owens received e-mails from Booker, Lynch, and Graham telling him what a great job he did.

“Observing you and your supervisors interacting with our officers was impressive… Nothing like proving the haters wrong,” Lynch’s e-mail reads.

And for a while, no one seemed alarmed at Marcellis’s conduct. At a command staff meeting two days after the protest on February 25, Owens said officers were amused by D'Addabbo’s description of how Marcellis carried a sign and marched alongside the protesters.

That all changed after The Maroon report and Zimmer’s subsequent letter to campus. Owens says that letter caused his life to “spira[l] out of control.”

“Prior to that [letter], the command staff laughed when they were told that Marcellis had stood with a sign and had some sticky mess on her lips,” Owens testified at trial. “Nothing occurred until [Zimmer’s] letter was released.”

On March 1, The Maroon published photos and conversations with protest organizers documenting Marcellis’s actions. Zimmer testified that he first became aware of Marcellis’s conduct from the Maroon article, although he threw some shade at the credibility of The Maroon's reporting.

“I would ordinarily not view The Maroon as a dispositive source of information and consequently would certainly have discussed its veracity with people internally,” Zimmer said at trial.

Following the Maroon report, Zimmer and then-Provost Thomas Rosenbaum sent an e-mail to the University community stating that Marcellis’s conduct was “totally antithetical to our values” and that such activity would “not be tolerated.”

On March 4, the day after Zimmer and Rosenbaum’s letter, Heath initiated an investigation into the February protest, placing Owens and Marcellis on paid administrative leave. The investigation took only 10 days. On March 14, the summary report found Marcellis and Owens guilty of bringing “discredit upon the Department.”

Zimmer and Rosenbaum’s letter had also promised to appoint an independent reviewer to investigate the incident.

The University retained Chicago law firm Schiff Hardin. In May 2013, the firm published a report favorable to UCPD leadership, reviewing UCPD responses to protests on January 27 and February 23. It concluded that no officers had behaved illegally, and blamed Owens for Marcellis’s actions, repeatedly citing Owens’s order for her to “blend in and get intel.” The report said there was no evidence that specific order was sanctioned by any commanding officer besides Owens.

However, Owens sought clarification prior to the protest on the vague instruction to “gather intelligence,” confirming with Booker that the goal was indeed to have Marcellis “mingle” with the protesters, according to testimony, and, eventually, to the defendants’ own court documents.

The most recent documents submitted by the defendants—post-trial motions for judgment notwithstanding verdict by Booker and the University—do not contest that Booker told Owens to have his officers “mingle and join in” with protesters. This is a shift in narrative from the story told in Heath’s report, which characterized Owens as having unilaterally decided that Marcellis should go undercover, while glossing over the reason for Owens’s instruction—direct orders from his superiors.

The Schiff Hardin report stressed the distinction between plainclothes and undercover officers, alleging that Owens was responsible for confusing the two.

“It was the intent of the officer who originated the demonstration plan that the term ‘plain clothes’ would mean detectives in the ordinary course walking alongside the protestors [sic] for safety and concern, but with all identifiers indicating that they were police officials, as had been done with protests in the past,” it read. “However, the commanding officer [Owens] in charge of the detectives’ assignment interpreted the term ‘plain clothes’ to be synonymous with an ‘undercover’ or ‘covert’ operation wherein the detective’s true identity would not be revealed.”

The University told The Maroon that the UCPD developed a protest and demonstration policy in 2013 as a response to the incident, so there were no specific guidelines in place regarding protests at the time.

According to UCPD Records Manager Connie Tsao, the plainclothes and undercover policy falls under General Order 604, Covert Operations/Vice Drug and Organized Crime Investigations, which is not available for citizen review “as it could disclose unique or specialized investigative techniques.”

Unlike the CPD and other departments, the UCPD does not make its General Orders available online.

The “old boys’ club”

The Maroon asked Owens why he thinks his former co-workers fired him and portrayed him as uniquely responsible for Marcellis’s actions. Owens believes it’s in part because he wasn’t “part of the clique.”

“I'm not a part of the good old boys’ club. All of them know each other. All of them came from universities. Lynch and Eric Heath came from Vanderbilt together,” he said. “I didn’t know any of these guys. Gloria Graham also knew them and I truly believe that it made it very easy, because I wasn't part of that, to throw me under the bus.”

Of the senior UCPD officers involved in the Owens case, only D’Addobbo and Heath remain at the University of Chicago. Booker is now Police Chief at University of Illinois at Chicago, while Lynch is Vice President of Safety at New York University.

Graham left the University of Chicago in September 2015, only a few months after Owens filed suit in May, to become assistant vice president and deputy chief of police at Northwestern. Just last week, Graham left Northwestern for University of Virginia.

On October 24, 2017, Judge Moira Johnson granted Zimmer summary judgment on all counts, and granted all defendants summary judgment on fraud, breach of contract, and promissory estoppel, which means violation of a promise enforceable by law. Summary judgment means that the judge thinks that there are no facts at issue and therefore issues a favorable ruling to the motioner, rather than having the claim go before a jury.

The court denied summary judgment to Lynch, Graham, Booker, and the University on the counts of infliction of emotional distress and spoliation of evidence. Johnson subsequently granted the defendants’ motion for directed verdict on spoliation claims, so only Owens’s claim of infliction of emotional distress was left standing for the jury to review at trial in January.

Missing videotapes and phones

In accordance with the ICS plan, officers Hughes and James captured the entire protest on a handheld video camera, filming from a UCPD squad car near the protest. However, the extensive video evidence of the protest was absent at trial.

According to the UCPD, the videotapes, along with the department-issued phones on which Marcellis and Owens communicated, were all misplaced and could not be located to be used as evidence.

Booker testified that at the end of the protest, Hughes and James returned the video camera to him. However, he maintained that he didn’t know what he did with the camera, did not know what happened with the cassette tape, and never looked at the video, inventoried it, or had anyone else watch the video.

Apparently, no video was preserved from any of the numerous security cameras posted throughout campus, either.

UCPD security camera feeds are only stored for 30 days if they are not preserved. Heath launched the internal investigation on March 4, only eight days after the video footage of the February 23 protest was recorded. This investigation alone would seem reason to preserve the tapes as evidence, but on top of that, Vroustouris sent Heath a preservation letter for all video related to the incident, among other materials. That request was sent on March 14, still within the period when the security tapes were available.

Neither the video captured by Hughes and James nor any security camera footage ever made it into the courtroom. Defendants claimed that Vroustouris should have directed his request to the University legal department, rather than directly to Heath, who was conducting the investigation.

The UCPD-issued phones over which Marcellis and Owens communicated on the day of the protest, which were confiscated when the detective and officer were put on administrative leave, also never made it to trial. Defendants testified that they were at some point returned to an evidence locker, but that they were subsequently misplaced or that the evidence locker was purged.

Owens told The Maroon he found command’s unwillingness to preserve or provide video evidence particularly egregious and considers it a violation of his right to a fair and thorough investigation, as codified in section 902 of the UCPD General Order on Complaint Investigation Procedures.

“Not only were the videotapes missing, the phones are gone. Marcellis’s phone and my phone, they're gone. At some point, even someone who just watches CSI knows something’s wrong,” Owens said.

Vroustouris told The Maroon he thinks the UCPD videotaped the protest in case protesters also took video and captured officers misbehaving, as they had in January, so that UCPD would have “their own version” of events.

The court granted the defendants’ motion for directed verdict on spoliation claims. At trial in January, the jury found in favor of Owens on his claim of reckless and intentional infliction of emotional distress.

On February 26, 2018, the defendants (the University and Booker) filed a motion for judgment notwithstanding the verdict, arguing that Owens’s claim of extreme infliction of emotional distress is insufficient as a matter of law. Such motions are rarely granted, but the University told The Maroon it intends to appeal the case, if necessary.

Owens now works in the security department at City Colleges of Chicago. He told The Maroon he regrets not staying at CPD, where he would have risen in the ranks and enjoyed union and pension benefits.

He is grateful to have the job at City Colleges, which has kept him afloat financially and mentally, he said.

Still, word of his firing has followed him, which is one reason it was so important to him to clear his name in court.

“I am not a very emotional person, but I actually lost control on the stand [and cried,] and they had to stop…after being in policing for a length of time, seeing the things that I’ve seen, you just learn to kind of separate your emotions from things,” he said. “But I was really embarrassed, to be honest. It just finally hit me—the betrayal.”

Marcellis, Heath, Booker, Lynch, the lawyers for the defense at Franczek Radelet P.C., and attorneys Patricia Brown Holmes and Kelly M. Warner, who authored the Schiff Hardin report, declined or did not respond to The Maroon’s requests for comment.