After enjoying a record-breaking box office opening for a foreign film, Bong Joon-ho’s Parasite might very well be the best film of the year. Following a unanimous Palme d’Or win at the 2019 Cannes Film Festival and a limited release in New York City and Los Angeles, Parasite is now showing in theaters across the country.

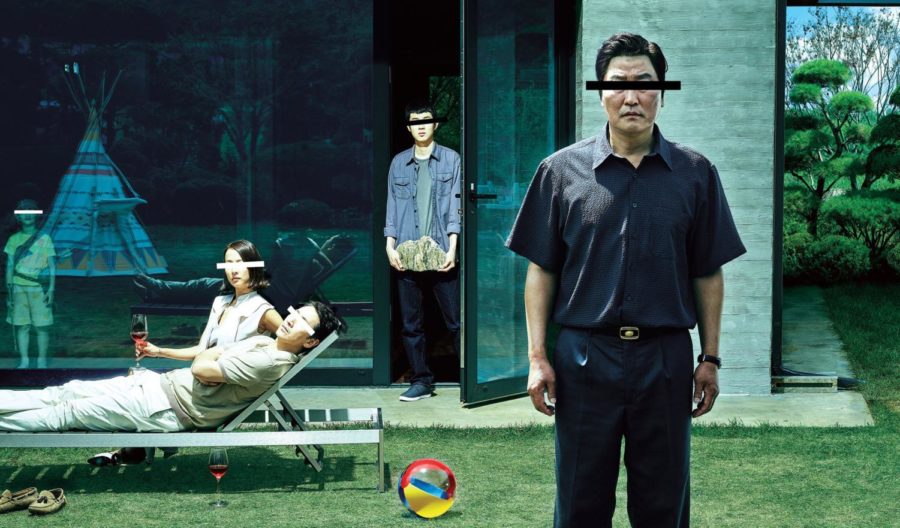

The film revolves around the relationship between the Kims, a down-and-out family of gig-economy and service-job workers, and the Parks, a wealthy family living in a former architect’s stately mansion. After falling into an English tutoring job for the Park family’s daughter, Ki-woo Kim’s (Choi Woo-shik) family finds ways for each member of their family to take on a job in the house while hiding the true nature of their familial bonds. The title Parasite seems to be a reference to the Kim family’s “leeching” of the rich Parks’ money through a series of hijinks and deception. At the same time, as the movie progresses and the Kims pull off their elaborate heist, it is increasingly clear that this is, in some ways, a codependent leeching, wherein the rich are unable to facilitate their own existence outside of the labor of the less fortunate.

Beyond this relationship and without revealing too much, the movie also questions the implications of fortune for each family. While the Parks are unscathed by economic relationships, environmental catastrophe, and personal struggles, the Kims are constantly digging their nails in, becoming more and more acutely aware of the extreme precariousness their momentary success relies on. The movie is a potent reminder of one of the fundamental conditions of contemporary capitalism––in a world of ever-widening stratification and inequality, there is always somebody below you, ready to grab your spot in the middle class.

As the movie digs into a complex web of familial and class relationships, it is simultaneously visceral and in-your-face while maintaining a hyper-neurotic attention to detail. Blood, urine, and sewage water flow freely alongside shots of perfectly manicured flora and carefully prepared fruit plates. The climax of the movie is as small as a wrinkle of the nose. This diligent attention to detail can be attributed to Joon-ho’s directing style, which includes detailed comic-like storyboarding and no coverage. The cast, while not star-studded to an American audience, includes veteran Korean actors including Joon-ho’s frequent collaborators Song Kang-ho and Choi Woo-shik.

The film has a distinctly Korean flavor––Korean cinema has a standing history of drawing attention to what some have labeled “dirt spoons” and “gold spoons,” or the visible and growing gap between the “haves” and the “have-nots.” This visible gap is driven home through an immaculate use of production design, from a tongue-in-cheek made-up Korean dish called “ramdon” to the way various lights are used throughout the movie to symbolize the resources available to a character at any given moment. The movie is at its strongest when it outlines the anatomy of these class distinctions, and at its weakest when it chooses instead to delve into individual character’s emotional or romantic obligations.

As it digs through the ever-expanding series of traumas and complexities embodied by the ensemble cast, the movie refuses neat genre categorization. Instead, it picks and chooses genre conventions from horror, comedy, and thriller movies that make even a bloody massacre seem tongue-in-cheek or cause a scene of familial solidarity to be laced with suspense. This slippage between lighthearted wry comedy and dramatic catastrophe drives home the scalar effects of poverty and exclusion. The laughter permeates the characters’ deepest traumas and hopes while they dream of escaping this twisted, parasitic system.

Parasite is currently showing at Chicago’s ArcLight Cinemas, AMC River East 21, Landmark’s Century Centre Cinema, and ShowPlace ICON Theatres at Roosevelt.