The Maroon sat down with Rian Johnson in October to discuss his new film Knives Out, an “unabashedly fun” whodunit, as a recent review in the Maroon put it. Also conducting the interview were reporters from DePaul Radio and the Loyola Phoenix.

DePaul Radio: To start out, I’m wondering how you made the decision to go from making smaller non-franchise films, then to Star Wars: The Last Jedi, and now back to your own films.

Rian Johnson: Well, I had a pretty blessed experience with Star Wars. In a lot of ways, it didn’t feel less personal than my other movies; it didn’t feel like I was “doing one for them” or whatever. I was very lucky in that respect. Besides that, if you look at it in ascending sizes, once you hit a Star Wars movie, there’s nowhere to go but smaller [laughs].

The truth is, this was just kind of the next big thing I had in my head that I wanted to do. It wasn’t a calculation or anything. I had the idea about 10 years ago, and it’s just kind of been in the back of my head. I actually wrote it very quickly, too; I sat down to write it last January and we had wrapped the movie by Christmas.

Chicago Maroon: Did you find that you bonded with some of the actors in the movie over similar experiences with moving from large-budget blockbusters to a smaller film?

RJ: It’s funny, we were all just enjoying the process so much. You’re right, most of us on set had been in huge movies in one form or another and also done small stuff. It’s like you’ve been through a war, like grandpa sharing war stories or something…. It kind of felt like summer camp and no one really wanted to bring up those outside things, so we didn’t really sit down too much to reminisce or anything. We did talk about it a little bit, though. Like, I talked with Michael Shannon, and he had a great experience in Man of Steel, and it was interesting to hear an actor’s perspective, especially a great actor like Michael, about what the challenges are working in an effects-heavy movie….

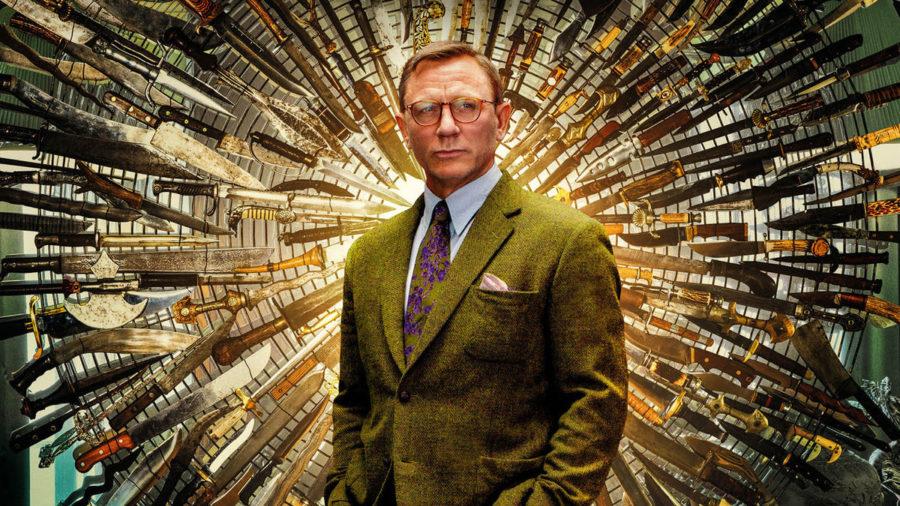

Loyola Phoenix: So, I grew up idolizing James Bond, so Daniel Craig has been one of my favorite actors. Between Logan Lucky and Knives Out, I’m starting to wonder whether James Bond robbed us of a really exceptional comedic actor…. His performance in a scene involving donut holes is probably one of the funniest things I’ve seen all year. So, where does the detective character Benoit Blanc that you wrote stop, and Daniel Craig’s Benoit Blanc begin?

RJ: That’s a really good question. It’s complex, and always hard to untangle after the fact. So much of what you see on the screen is Daniel. Not in terms of improv or anything, he’s still reading from the script. But what I wanted for the part is to find someone who would be a collaborator and create something on the screen that I could not have even imagined on the page. Obviously, I knew Daniel from Bond, and if you only know him from that you might imagine he’s kind of an intense, serious dude. But he’s not, he’s a blast. He’s not like Blanc either [laughs], but having met him a few times over the years I knew he had a sense of humor.

Again, it wasn’t so much improvising, but he really created this character in other ways. Once we found the accent and got on set, I just got to be along for the ride and enjoy his instincts and his performance.

DR: So, you’re saying during scenes, you would sit back and enjoy the show. That said, shooting in a very Gothic, old house, how do you control for all these big A-List actors within such a confined environment?

RJ: First, in terms of having all these big personalities on set, that was very easy. I was actually nervous about that at the beginning because I didn’t know what that would be like. The truth is that having all those people together in a concentrated space, everyone just showed up ready to have fun. Everyone checked their egos at the door, there was no movie star nonsense. I think the fact that we were in this house in the middle of Massachusetts probably actually helped. No one would go back to their trailers, everyone would just go down to the basement and hang out between scenes. It was really this summer camp environment.

Speaking technically, from a filmmaking standpoint the thing that was a challenge was actually blocking scenes for eight people: covering them, figuring out the best angles, figuring out the best ways to get everyone their moment without spending all day doing coverage. That was kind of my biggest challenge making the movie, and the first time I’ve had to do that with so many people in a room.

CM: Last night at the Chicago International Film Festival Q&A, you mentioned that you wanted to make this movie a “real” whodunnit, not a parody of the genre. That said, there is a lot of over-the-top comedic performances in the film. How did you tread the line of having cartoonish comedic elements and also an earnest approach to making a film in such a specific genre?

RJ: Well, I think you have to have an internal compass for it, so that you can recognize “This is what feels right to me,” and you kind of just have to trust that. I mean, some of the whodunnits that I grew up watching—like Death on the Nile and Evil Under the Sun, which had the great Peter Ustinov playing Poirot—had actors going very big with their performances. Maybe that’s something that made me feel comfortable with the over-the-top elements of the genre. Even Agatha Christie, at least how I read her books, always draws her characters just to the edge of caricature. They’re always blown up. They’re not subtle and nuanced character studies; her characters are big, splashy caricatures of British society. At the same time, they still have a recognizable humanity to them. So, all of those were kind of the targets I was aiming for. At the end of the day, it’s also just supposed to be a fun movie!

LP: So, we’ve been talking about all these different pieces of Knives Out: it’s a whodunnit, it’s a comedy, it’s got all these meta things, and it’s also a social commentary on our times. And that’s true of all your movies. Can you talk a little about how you being a movie fan has influenced your goals with what you want to convey in your movies?

RJ: Thank you, I consider that a big compliment. When I was a kid, I started out being a fan of E.T. and Raiders of the Lost Ark and Star Wars, that was kind of the bedrock. And when I got to film school, I started getting into European art films. And I guess I continue to love big Hollywood stuff and smaller weird stuff—I love them equally. I love movies that feel like they give you nourishment, not in terms of a lesson or any finger-wagging moral, but really give you something to chew on. A lot of times you associate that with smaller art house movies, but I guess my goal is to make the Venn diagram of art house and blockbuster one single circle. I think entertainment is not incompatible with substance, and a lot of movies that are released every year prove that to be the case. I want to make things that are really entertaining rides, but also give you things to chew on, absorb, and be satisfied by on a few levels. To me, something is not truly entertaining unless it’s all of those things.

DR: When did you know that you wanted to make the social commentary a part of the story?

RJ: Very early. For me, I can’t start writing until I have two elements: I need some kind of conceptual plot or genre element I’m excited about, and I also need something that I care about. Whether you call it theme or whatever, I need something that I’m angry or excited about or want to explore. And it’s only when these two elements lock together like gears—not one on top of the other, or one hidden in the other, but genuinely work together as a single piece—that I can feel happy about a script. What I’m aiming for is that what I’m trying to express thematically is in the bones of the story, as opposed to something you can hang on it like ornaments. And that’s when this film got really exciting for me, the idea that these issues we all have on our minds could be explored by using this type of story. That’s always the goal, not hiding a message, but using the story to explore something really interesting.

CM: And I think the centerpiece of the movie, and the center point of a lot of the social commentary, in a lot of ways is Ana de Armas’s character. How did you decide to make this inversion of the “the butler did it” trope by essentially centering the movie around a character that would usually be in the background of a whodunnit?

RJ: I think in most detective stories, you’re never seeing the story through the eyes of the detective. There’s always a secondary character who is one step behind the detective who you’re seeing the story through. That’s why you have Watson to Sherlock Holmes…. And that’s critical because the detective has to be an enigma to the audience. And first and foremost, that’s what the character of Marta is to me. It is interesting to think about “the butler did it,” I wasn’t really thinking about that. Her character mostly gave me an opportunity to play with how the mechanics of a whodunnit are perceived by the audience.

LP: With the fact that you wrote it, produced it, and directed it in such a short time frame, can you talk about how your sense of urgency in filmmaking changed with you as a producer?

RJ: Well, I have an amazing producer called Ram Bergman who I’ve been working with since Brick, and Ram is the reason I’m still making movies today. I know lots of filmmakers who had their first films around when I did Brick who are more talented than I am, but didn’t have a Ram in their lives. So, I’m very grateful to have that guy. In terms of producing, he’s the man. Creatively, we’re also partners in everything we do, so I get a lot of creative input from him on the scripts and stuff. So, the process for this movie was very similar to our other movies, and since we started this production company together we just thought this time we’d both take the co-producer credit. The truth is, in terms of the split of the labor, it’s very similar to everything else we’ve done. And honestly, it’s a miracle that we were able to schedule all these actors [laughs]. It’s like juggling cats with their schedules, and Ram is really a genius at that.

DR: You’ve talked about your influences in the whodunit genre. Are there any off-kilter movies or books that influenced Knives Out? We don’t really see that many entries in the comedic murder-mystery genre these days.

RJ: I’m a whodunnit junkie. I thought the Kenneth Branagh Murder on the Orient Express was really fun, I really liked that. I dug the Adam Sandler one that came out too, but I also just love Sandler. There’s nothing like, “Oh, I actually drew from I Am Cuba,” or anything like that. But there is a weird whodunnit called The Last of Sheila that not a lot of people have heard of. It was written by Stephen Sondheim and Anthony Perkins, and it’s this weird ’70s murder-mystery. That’s one to look up.

CM: Alright, looking forward, do you have anything we can be expecting from you? Any plans to return to TV directing maybe?

RJ: I would love to do some more TV directing. I mean that’s the way to just get down to the nitty gritty of filmmaking and not getting precious about it. I feel like I got so lucky getting to do a little on that show Breaking Bad that I feel like maybe I won the lottery and should quit while I’m ahead [laughs]. But I’ll definitely go back to it someday, and that’s actually one of the things that Ram and I are working on. So, we’ll see.

Knives Out is out now. Check out the Maroon’s review of the film.