The Museum of Contemporary Art recently presented choreographer Ingri Fiksdal and dramaturg Jonas Corell Petersen’s STATE—a striking performance art piece that uses dance and a fluid performer-audience relationship to explore the role of rituals in shaping national identity. Despite the work’s distinctly political title, Fiksdal and Petersen’s collaboration displayed a wholly abstract and interpretive vision within which the audience could find their own realities.

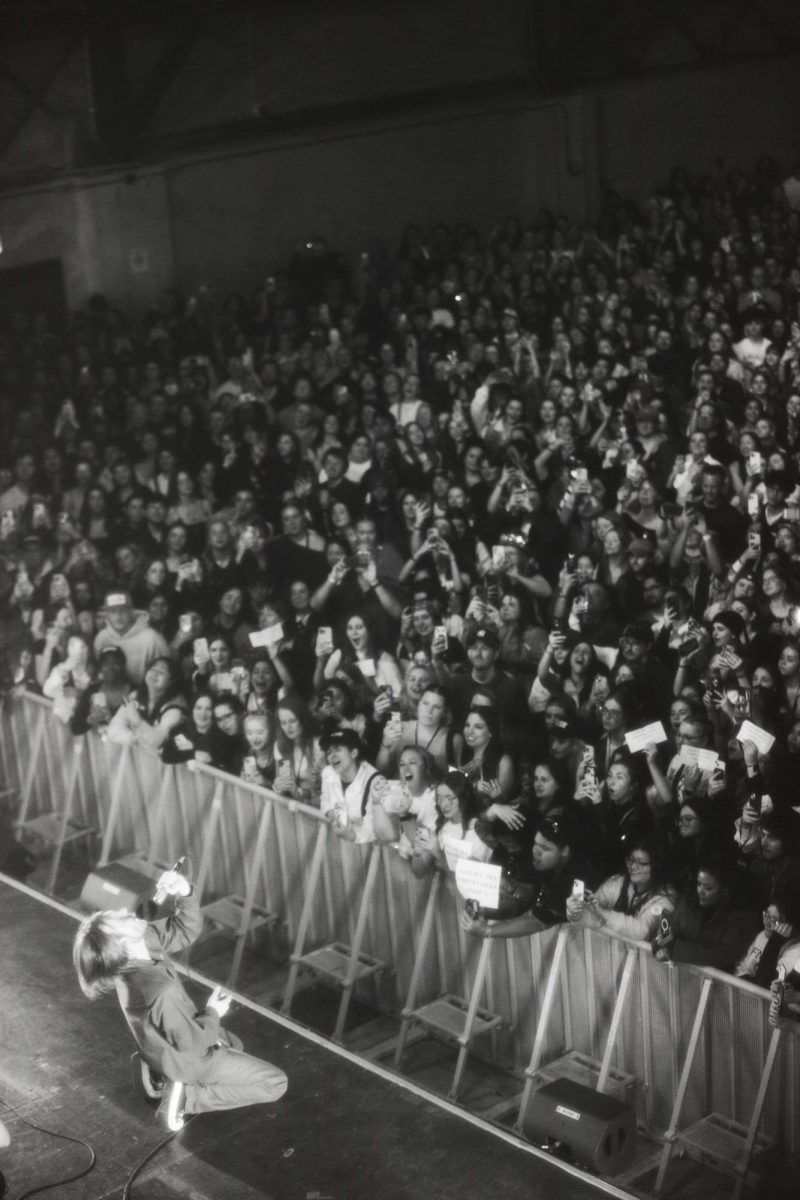

Fiksdal and Petersen’s exploration began from the moment I entered the theater. The audience was seated in a circle surrounding the stage, and members where personally welcomed by a performer serving apple ginger juice. Other performers and production team members casually walked around the stage preparing for the performance, impassive toward audience members nervously sipping on their appetizers. For a moment, the space was hospitable and normal; the performers and audience were all real people in a real world.

This rapidly changed when the dancers suddenly gathered into the middle and began putting on their costumes, as the lady who served juice sprayed smoke all around the dancers. Lasse Marhaug’s metallic soundscape saturated the air, and the hospitable theater transformed into a grave, abstract realm, where STATE’s themes were to be confronted.

Fiksdal’s choreography takes inspiration from sources as various as classical ballet, ceremonial dances, and military marches to form a uniquely comprehensible physical language about uniformity and conformity. The five dancers’ presence was intimidating as they traveled across the stage in perfect unison, performing eerie and striking movements in unsettlingly close proximity to the audience. However, at certain points of the choreography, one dancer would break off and begin a new dance sequence, contrasting with the movements of the original group. Despite these brief moments of individuality, the outlier would soon rejoin the original group, or others would join the outlier until their movement became the new norm. In doing so, Fiksdal asks whether individuality and autonomy really exist in an institutionalized environment, controlled by a centralized state. Perhaps we are always tending toward acceptance and a norm, despite our desires to be free individuals.

This tension between the individual and the masses is further heightened by Henrik Vibskov’s dynamic costumes. While all five performers wore the same costumes, the garments failed to fully conceal each dancer’s distinct skin tone, height, and size. The garments swung and sat differently according to who was wearing them, and it was difficult to ignore the inevitable, biological resistance toward the infallible uniformity that the choreography and costumes tried to embody.

The last scene was more ceremonial, even ethereal, as a solo dancer spun in a tight spotlight for around five minutes, intoxicating the audience. The silence felt unnatural as Marhaug’s harsh soundscape—which at this point had become white noise—came to an end, but the audience soon filled the gap with rapturous applause. STATE is more than a political piece; it was a performance exploring the nature of human society that transcends the boundaries and expectations of time. This multifaceted, collaborative work poses questions that allow the audience members to reflect on our own constructed identity, thereby enabling us to imagine a future where such tensions might be alleviated.