There are few things more disorienting to a Millennial or Gen Zer than discovering that something’s not on Google. It feels like a betrayal to a generation that kind of expects to find the neighborhood cats on social media (I’m looking at you, Nestor) or catch serial killers through Ancestry.com.

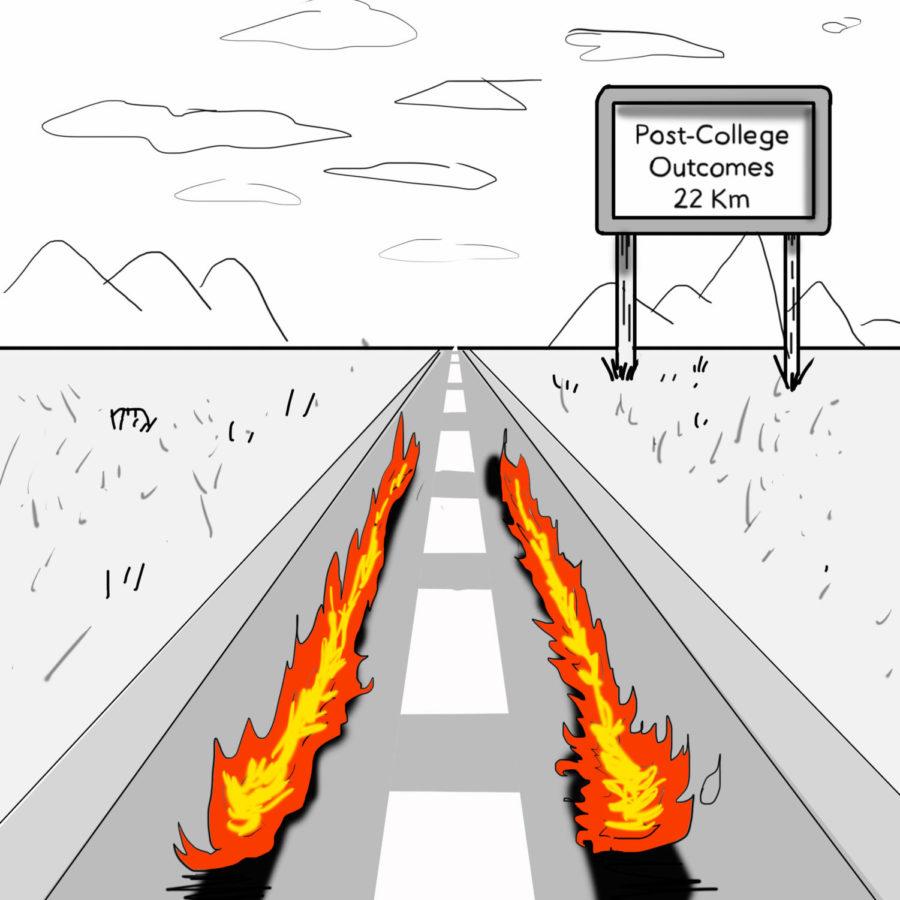

So I just assumed that, if I wanted to know about student outcomes at different colleges, the information would be out there, somewhere. And as a fourth-year, that information has become salient again: This entire year has been a stretch of whiplash, alternating between periods of quiet senioritis and job-search pandemonium. The variation in what people are doing is astonishing—from committing themselves to more school (voluntarily! On purpose!), to consulting, to even more consulting. There are also differences in students’ timelines: Some are grappling with the pressing issue of which industry they should work in, while others have moved on to those equally pressing issues of decor, like which succulent will look best in their cubicle.

It’s impossible to watch this scramble and not wonder what’s happening, and how UChicago fourth-years compare to those at different schools. Which is why I found myself trying to figure out what the average graduate from UChicago is actually up to. I didn’t think this was a very stalker-ish effort (it’s not like I’m trying to reverse engineer anyone’s starting paycheck), but apparently it’s beyond the pale.

As it turns out, there’s relatively little detailed information to be found. You can, for instance, find graduation rates, average annual costs, and median salaries on College Scorecard. For the University of Chicago, that’s a 93 percent graduation rate, an average annual cost of $19,510, and a median salary of $68,100, 10 years after entering the school. But even this isn’t very illuminating—College Scorecard has removed the national median lines it once provided for a quick comparison.

For students considering predatory institutions (think of the particularly low-quality, for-profit colleges) with abysmal graduation rates, sky-high costs, or low salaries, that missing line is a serious problem. There are plenty of people out there who might not realize that a 60 percent graduation rate is only mediocre and anything less than 30 percent is appalling, and plenty of institutions are eager to capitalize on that ignorance. Unsurprisingly, the decision to scrap the national median markers led to an immediate backlash.

But even for those of you cyber-stalking top-tier schools, you could be forgiven for concluding that College Scorecard’s pretty, graphic-filled pages are telling you nothing at all. That median salary information? It’s gathered 10 years after students enter their universities; if you’re an undergrad who graduates on time, that’s six years after you’ve left. You might think that six years post-graduation is a reasonable time to check in on salaries (and for many institutions, it probably is), but a quick look at our university’s website tells you that some 85 percent of UChicago students are attending or have gone to graduate school within five years of graduation. A large portion of the student body is back in school, or just out of school again, at College Scorecard’s 10-year mark. Reporting median salaries at this time alone might tell you a lot, or it might tell you absolutely nothing. And don’t bother trying to break down salary information or grad school attendance rates to a more granular level; that data isn’t available on College Scorecard yet, though the Department of Education has promised to introduce within-institution salary data by program at some undisclosed date. Detailed salary information by major is technically already available—but its accuracy is the subject of contention, because these measures tend to rely on small samples of self-reporting alumni. Attempts to produce detailed, actionable measures of the return on investment for different colleges have been bogged down by those issues.

When universities do release their own information (check out UChicago’s Class of 2017 outcomes report as an example), it tends to be carefully curated. Granted, some of the report is fascinating: 33 percent of the Class of 2017 went into “financial services and other business,” and another 12 percent are in consulting. But some of it is less helpful. As an example of how the most mundane facts can be spun, check out this very comforting reassurance that “during their first year, every Class of 2017 student received an assigned career adviser.” That’s right—“received.” Not “met.” That’s front and center and bolded. If you want to peer into the black box of higher education outcomes, this sort of report isn’t the place.

I’m not suggesting that a promotional brochure is the place for full transparency and extreme detail. But sites like College Scorecard are supposed to make students’ choices less opaque, not opaque-but-with-charts. Students deserve to have information they can easily access and actually use. That’s not to say that most students do or should make their choices on the basis of expected salary alone; if this were a primary motivation, we’d all be finance bros. But for students weighing their options, expected outcomes are often very relevant, and general intuition about what a degree might lead you to (which grad schools, what salaries, which companies?) just doesn’t cut it. Tons of students are weighing their options—remember those few months in your first year when you probably cycled through every major in the course catalog, and then considered a few that don’t actually exist, just for good measure? Colleges are teeming with students who have already changed their minds about what they’re doing, and are going to change their minds again. The tools students do have aren’t always sufficient to make informed choices.

They certainly aren’t enough for students who view their degree as a primarily financial investment. There’s evidence that students at less-selective institutions in particular are more likely to see college as a quick route to a relatively high-paying job. For those students who do see college primarily as a financial investment, good information on expected student outcomes is absolutely critical—but we don’t really have it yet. That’s a shame. Better information may not be a glamorous thing to rally around; nevertheless, as a key component of how students make tremendously important decisions, it’s an issue worth caring about.

Natalie Denby is a fourth-year in the College.