Law professor Geoffrey Stone had been saying a racial epithet in his First Amendment class for over 40 years to explain the “fighting words” doctrine. After a spontaneous and emotional conversation with several Black Law students in the Law School’s main lounge last week, he has decided to stop.

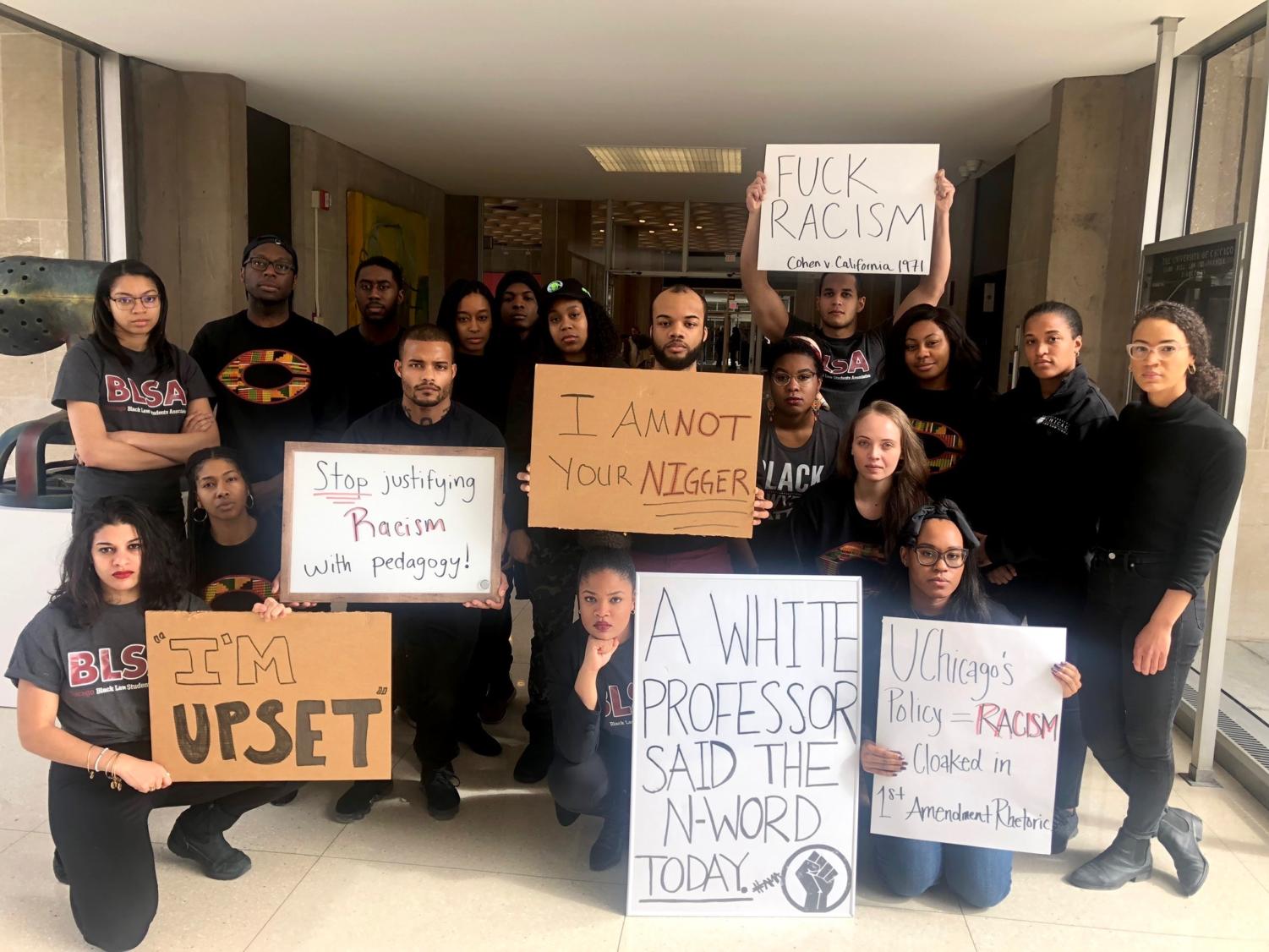

Following heated discussions about a recent op-ed sharply critical of Stone’s use of the slur, several members of the Black Law Students Association (BLSA) decided to demonstrate in the main lounge last Wednesday. In addition to protesting Stone’s use of the racial epithet, BLSA members wanted to share their frustration after years of trying to push forward various diversity initiatives through the Law School administration.

What began as a small demonstration of 15 BLSA members grew to a crowd of almost 200 students and faculty members. When Stone happened to walk in during the demonstration, BLSA members asked him to listen as they explained in impassioned speeches the harm that hearing the slur in class can cause.

Less than an hour later in lecture, Stone announced that he would no longer say the slur in class.

The decision marks a shift in the perspective of Stone, a former dean of the Law School and provost of the University, who has written extensively about protecting free speech rights and chaired the committee that drafted the University’s Chicago Principles document on free expression in 2014. It also marks a departure from how University administrators have interpreted the University’s avowed dedication to free expression. Administrators have generally held that students’ emotions are not a sufficient reason to limit information.

In 2016, Dean of Students John “Jay” Ellison wrote in a letter to the then-incoming undergraduate Class of 2020 that as part of committing to academic freedom, administrators “do not support so-called ‘trigger warnings’” and “do not condone the creation of intellectual ‘safe spaces.’”

Stone claims that national and on-campus calls to limit the use of the slur in academic settings have grown more vocal in recent decades, but that he was not influenced by public backlash, and instead made his decision after witnessing and hearing the strong emotions of the Law students who talked to him.

Stone’s Long-Running Use of the Slur

Stone is currently best-known as one of the foremost free speech scholars nationwide. Last December, he published his most recent book on the evolution of free speech doctrine. The book was co-authored with Columbia University President Lee Bollinger, who has taken a stance on free speech similar to that of UChicago President Robert J. Zimmer.

For over 40 years, Stone has been telling the same anecdote to his First Amendment class and at guest lectures at other schools when teaching the fighting words doctrine. This doctrine holds that expressions of words that incite violence are not constitutionally protected by the First Amendment.

Stone would tell the anecdote as follows: In class over 40 years ago, a Black student said that the fighting words doctrine is outdated because words long deemed as “fighting words” no longer provoke violence. A white classmate then called the Black student the slur, saying, “That’s the stupidest thing I’ve ever heard.” This prompted the Black student to reach over and grab the white classmate by the neck. Stone believes the white student’s use of the slur and the Black student’s response in that moment precisely demonstrate the continued relevance of the fighting words doctrine.

In an interview with The Maroon late last week, Stone explained why he had been using the full epithet when telling the anecdote.

“It’s important, If you’re teaching a legal concept, to use the words that are the subject of the legal prohibition and to ask, ‘should they be [legally prohibited]?’” For Stone, an important part of discussing why certain words are prohibited is to confront the harm that they can cause by saying the words in full.

“It’s utterly inexcusable to use the word for the purpose of degrading and insulting someone, but it’s a word that exists in our history, in our society, in our law, and you need to address it,” he said. “Not addressing it is almost failing to acknowledge how ugly and how offensive it is.”

He added that limiting the use of the epithet has broader implications, saying, “Once you say you’re not going to say this word, you’re inviting endless discussions about any other words on the list, the concepts on the list, and what else offends or upsets people.”

Stone said that his past stance was consistent with the norm of other contemporary legal scholars, citing Randall Kennedy, a Black professor at Harvard Law School. Kennedy wrote an op-ed in The Chronicle of Higher Education last month criticizing the administration of Augsburg University in Minneapolis for suspending a professor who said the racial slur in class when discussing literature by James Baldwin, and has also written a book specifically about the slur.

“Until relatively recently, the word didn’t have the same inflammatory quality as it’s come to have,” Stone said. He mentioned that he had asked Black students about his use of the epithet in the past and they “thought it was a powerful example.”

Kamara Nwosu, vice president of BLSA, said in an interview with The Maroon that students are often intimidated to confront professors about their teaching.

“Almost every single professor is at the top of their field, and when you’re trying to break into these fields academically or professionally, you would be more cautious in your interactions with professors,” she said. “You’re not going to want to outright criticize them.”

In the same interview, BLSA President Amiri Lampley challenged the notion that the epithet has only grown inflammatory in recent years, saying, “Generations before us may not have felt that open to speak out about this, and had bigger problems to fight than the N-word.”

Lampley and Nwosu, who had heard from other students about Stone’s use of the epithet in January, had brought it up with Charles Todd, the dean of students in the Law School. He “said that [administrators] can’t take a stance and can’t reprimand faculty for the speech they decide to use as long as they’re not disruptive to the Law School,” Lampley said.

Black Law Students’ Exercise of Speech

Members of BLSA have long been frustrated with the Law School administration’s lack of commitment to fostering more supportive cultures and practices at the school. Lampley cited the University’s inaction toward a campus debate group’s publication of a whip sheet that said immigrants bring “disease” into the body politic. Nwosu noted that the administration has held listening tours to develop diversity recommendations, but “none of them have been truly implemented in the classroom, in class offerings.”

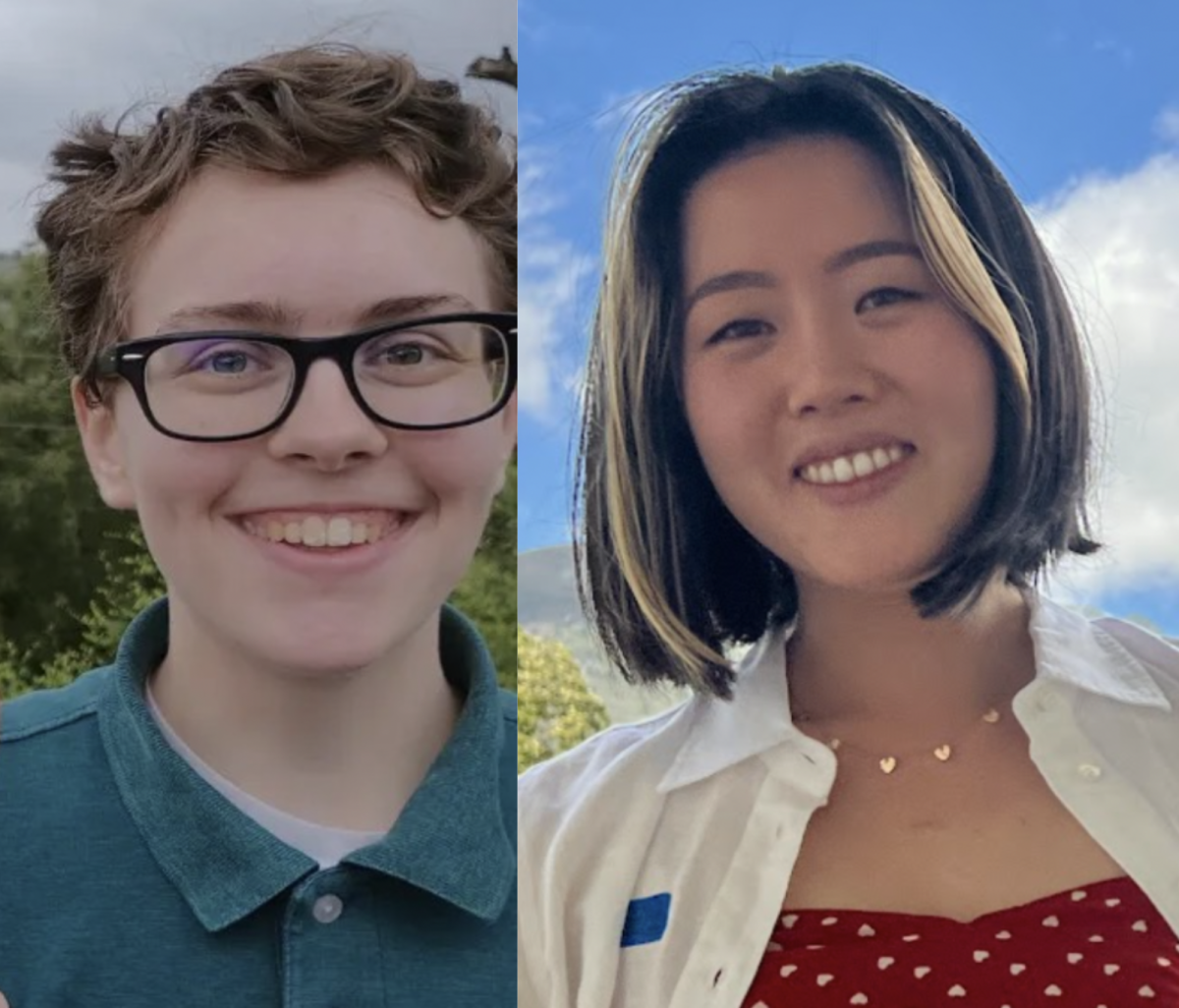

BLSA members ultimately decided to demonstrate last week after seeing reactions to an op-ed in The Maroon criticizing Stone’s use of the slur. After the op-ed was published last Tuesday, the author—second-year Law student and third-year Harris student David Raban—sent it to a GroupMe chat of Law School students. A debate erupted in the chat on why discussion of Stone’s use of the slur was necessary. Lampley said the debate showed her that among some students there is “insensitivity and ignorance surrounding…the history of the N-word, how its use has been used to segregate and denigrate people for years.”

The GroupMe debate prompted BLSA members to stage an impromptu demonstration in the main lounge the next morning, Lampley and Nwosu said. They wanted to incite the administration to act and also show other students what Black students’ experiences at the Law School have felt like.

At lunchtime, Stone happened to pass through the main lounge to buy lunch and several BLSA members asked to speak with him about his use of the slur. They sat down, and in the ensuing 30-minute conversation, which drew nearly 200 students and faculty members, Stone listened to BLSA members explain at length the harm that hearing the slur in class can cause.

They told Stone that his use of the full slur “is not as effective as he wants it to be,” Lampley said. They stressed to him that “It actually damages and disrupts and distracts students from learning which outweighs the benefits he thinks he gains from it.”

Lampley said that in response to Stone’s claim that students need to understand the gravity of the epithet, BLSA members told him, “We totally understand the immensity that the word carries.”

“Anyone can understand the impact of the N-word without explicitly saying it.”

In an email summarizing the discussion, Lampley said that BLSA members also told Stone, “The culture that has allowed this tradition to go on without denunciating its practice, speaks to the entrenched systemic racism woven within the fabric of the University and America.”

Lampley continued in the summary, “Contrary to what Professor Stone or other proponents of the Law School’s free speech policy might believe, we actually encourage and have requested, time and time again, more opportunities for civil, public discourse, engaging with contentious topics that address sexuality, gender, and race, that recognizes America’s legal history of oppression and inequitable practices.”

By the end of the conversation, emotions were high and several students were in tears. Stone said that he would consider whether to stop saying the epithet.

Stone’s Reconsideration

After talking with the Law students, Stone had less than an hour before his First Amendment class.

He said he ultimately decided that “though there was value in using the word, this was a situation where the cost was greater than the benefit.”

“I never appreciated, before, the extent to which [hearing the slur] was disconcerting and painful,” Stone said, adding that the conversation in the lounge “gave me a very different understanding that these arguments are not just political correctness, that there’s really something powerful there, and I found that very moving.”

“It’s not essential,” he said he realized about saying the slur. “It’s the distinction between useful or important and essential. There are lots of things that you don’t do in a classroom as a teacher which might be useful, but you don’t do them for whatever reasons.”

Stone added that he considered his decision through a personal lens. He said he has two half-Black grandchildren and he realized he would not want his grandchildren “to have to face this reality and sit there and go through what these students are going through.”

Though Raban’s op-ed did raise strong criticisms against Stone, Stone maintains that he decided to stop saying the slur not in fear of public backlash, but after being persuaded by the Law students in the lounge.

“They had the opportunity to say what they had to say to me, and did it so effectively,” he said. “I listened and changed my mind. That’s what free speech is about.”

In lecture, he announced to the class that he would no longer say the full epithet and tell the anecdote in class anymore. He told The Maroon that if the epithet comes up in his class, he “will refer to it as ‘the N-word.’”

Asked for comment on Stone’s past use of the epithet and his change of mind, the University said in a statement to The Maroon, “We believe universities have an important role as places where controversial ideas can be proposed, tested, and debated by faculty and students. Faculty members have broad freedom in the choice of ideas to discuss in the classroom and in their expression of those ideas, and students are free to express their views on those subjects.”

Nwosu said she has a “mixed bag” reaction to Stone’s announcement that he would stop saying the epithet. She said she believed BLSA had “achieved something small,” but was disappointed that Stone had only announced his decision in class and had not officially communicated to BLSA his decision.

“This was a conversation with BLSA members, so I hoped he would articulate to us directly,” she said. She would have liked if Stone had “called up the dean of the Law School to have a conversation with members of BLSA, maybe also the dean of students, just to wrap up the whole situation.”

“That would have been a nice wrap up.”

Editor’s note: The Maroon avoids gratuitous use of racial slurs. We publish such words only when they are essential to understanding the story. We did not publish the epithet in question in this article because the article provides sufficient context. See the Associated Press’ policy on obscenities, profanities, and vulgarities for reference.

The Maroon quotes sources verbatim. Where we have styled the epithet as “N-word,” this is a direct quote — that is, we are quoting people who said “N-word” in interviews