Former president of the American Civil Liberties Union Nadine Strossen has said she was motivated by recent debates over the role of free speech on campuses to write her 2018 book HATE: Why We Should Resist It With Free Speech, Not Censorship.

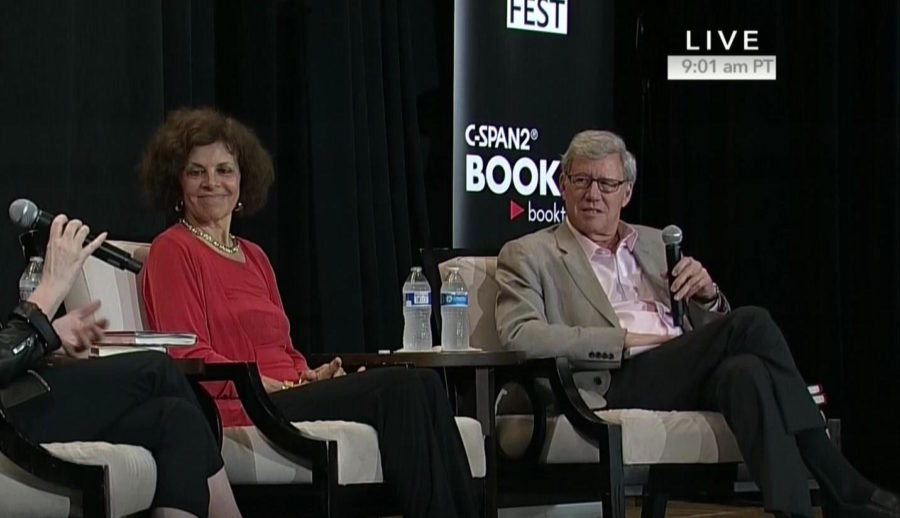

On Tuesday—several weeks after the Law School’s racial and ethnic affinity groups challenged the University's application of its Chicago Principles on free speech—Strossen came to the Law School to discuss her book with law professor Geoffrey Stone.

Stone edited Strossen’s book and chaired the University committee that drafted the Chicago Principles. He was also the subject of the recent controversy involving the affinity groups: For many years, he had been saying a racial epithet in class to illustrate a legal doctrine. Last month, affinity groups expressed their disapproval that the University had not condemned Stone’s use of the epithet.

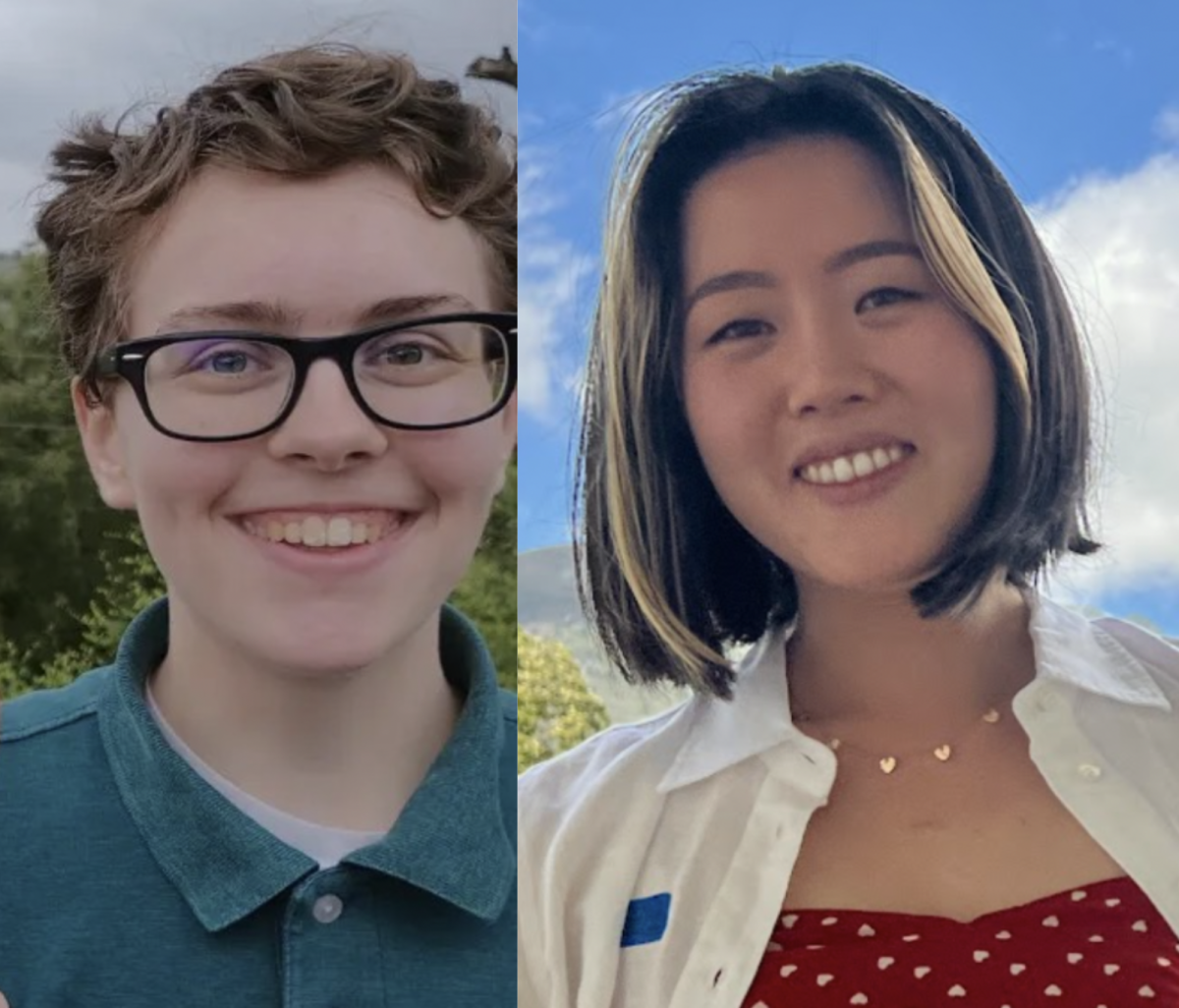

The Law School’s American Constitution Society invited Strossen to campus, and the talk was co-hosted with other student groups, including several affinity groups. Kelly Yin, co-president of the Asian Pacific American Law Students Association (APALSA), said that APALSA had discussed pulling out of the event in light of last month’s controversy, “but decided against it primarily because the issues discussed at the talk are still relevant to APALSA as an affinity group.”

“Hate speech”—defined as derogatory speech prejudiced against certain groups—was the focus of the talk. Strossen explained why she believes a policy of censoring hate speech would not be feasible and why shaping such a policy should not be in the hands of the federal government or, by extension, public universities.

Strossen told The Maroon following the talk that she believes that private universities should maintain these standards as well: “By a principle of good pedagogy, [private universities] should voluntarily follow the same First Amendment standards that public universities are required to follow.”

Tuesday’s programming at the Law School also involved real-life free speech tensions: Next door to the talk, non-student pro-Palestinian protesters interrupted a visiting professor’s lecture on the application of laws opposing the Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions movement under the First Amendment. The protestors were escorted out by UChicago police officers, and the Law School’s dean of students said in an e-mail to students that the protestors’ chanting “did violate the University’s policies” on free expression.

“It is the right of any speaker invited to our campus to be heard and for all who choose to be present to hear the speaker,” the dean of students wrote. “Protests that prevent a speaker from being heard limit the freedoms of other students to listen, engage, and learn.”

Difficulty of Defining “Hate Speech”

In the talk, Strossen said that what many people deem “hate speech” is not a category of speech defined by the Supreme Court.

“I put that term [‘hate speech’] in quotation marks throughout my book to underscore that unlike ‘obscenity,’ it’s not a constitutional law term of art,” she said.

Strossen added that while “hate speech” is not defined by the Supreme Court, there are types of speech that are currently prohibited by law when they are expressed in particular contexts, specifically speech that poses a direct threat, harassment, or incitement of immediate violence.

Strossen also questioned the feasibility of defining what a category of “hate speech” would include. She said that hate, “which after all is an emotion,” does not have “an objective definition.”

“There are many examples from around the world where one person’s hating idea is one person’s loving idea,” she said, citing different religious views on gay marriage.

In past talks about her book, Strossen had put out opens calls for people to notify her if they could create a “hate speech code that does not censor speech that nobody wants to censor,” adding that “it has been tried and tried and tried.”

Weighing Who Deals with Hateful Speech

Stone asked Strossen, “Aren’t there viewpoints that one can say are so incompatible with the fundamental values of our Constitution that they should not be protected?”

Strossen answered by weighing who within society should address hateful expressions.

“I always ask myself, ‘What is the lesser of two evils?’” she said. “Would I rather trust my fellow citizens to rebut those [hateful] ideas and to have robust counter-speech and education, or would I rather trust the government to decide that some ideas are so wrong and so dangerous that the government will punish them?”

She noted that in a majoritarian democracy, the government is “much more likely to protect ideas that are popular to the majority,” and so hate speech laws would be, and have been in other countries, “disproportionately enforced against minority groups.”

Strossen said that while she believes the government should not determine what speech should be censored, she also believes that public actors should be able to denounce hateful speech that they deem are inconsistent with values of their community: “In a [public] university setting for example…I think that universities should strongly affirm basic values, not only freedom of speech but also equality and diversity and inclusivity.”

Asked after the talk whether she believes her views apply to private universities, Strossen told The Maroon that they do, as she believes that private universities should “educate [students] and prepare them for the democratic public.”

As American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) president, Strossen previously supported a 1991 bill sponsored by Illinois Representative Henry Hyde that would have held private universities that receive federal funding to the same First Amendment standards as public universities. However, when asked whether she supports the recent executive order signed by President Donald Trump that would pull federal funding from private universities if they don’t “promote free inquiry,” Strossen told The Maroon that she doesn’t.

She explained that the bill sponsored by Hyde aimed to bind private universities to First Amendment standards in court, unlike the executive order which prescribes a standard determined by the president's office: “The Constitution would have been the standard [under the 1991 bill], rather than some bureaucracy.”

Countering “Hate Speech” with "Counter-Speech"

In past talks, Strossen has repeatedly emphasized that while she believes hateful speech should not be censored, she doesn’t believe people should passively accept it. Rather, she believes people should oppose it with “counter-speech.”

On Tuesday, Strossen aimed to focus her discussion of counter-speech around last month’s controversy at the Law School by addressing the use of racial epithets.

In a paper handed out before the talk, Strossen argued that if people restrain themselves from expressing certain words, they can more effectively challenge others’ opinions and persuade others of their own opinion in “counter-speech.” She explained that she tried to do this in her book when she used the term “N-word” in place of the full word. She did not want to provoke negative reactions from readers that would distract them from her main argument.

When asked to comment on Stone’s decision to stop saying the racial epithet in class, Strossen told The Maroon that she found it “interesting” to see Stone express in interviews the same mindset she had when writing the book—which is that “you have to balance what is the educational benefit versus what is the detriment.”