Graduate Students United (GSU) announced Wednesday that they are holding a strike authorization vote, a move that represents a major escalation of GSU’s ongoing efforts to bargain with University of Chicago’s administration.

Members began voting on Wednesday and will cast their ballots through the weekend to decide whether the union should go on its first strike.

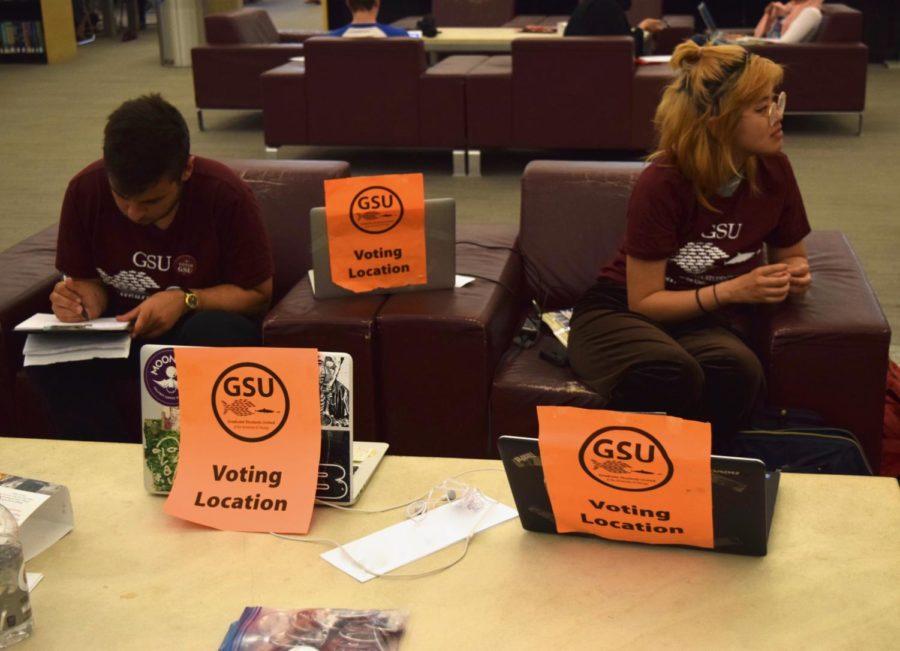

In-person polling locations at the Regenstein Library, Quantum Café, and the School of Social Service Administration are open through Friday afternoon. Online voting closes Sunday. GSU will release the results of the vote next week, GSU co-president Claudio Gonzáles told The Maroon.

The specifics of a strike—including when it would take place and what it would entail—would be decided only after the polls close, in the event of the strike authorization vote’s passing. In conversations with The Maroon, GSU members have individually voiced support for strategies such as not leading classes, leaving papers ungraded, and encouraging support from undergraduates. A strike would likely be held before the end of this academic year.

Though graduate students voted to unionize 19 months ago, the administration has not recognized the union. Last February, GSU withdrew its certificate of representation from the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB), fearing that a Republican-controlled NLRB would use their case to revoke the ability of graduate student labor to unionize nationwide. The organization continues to seek voluntary recognition from the University of Chicago.

GSU has used a variety of demonstrations and tactics, including a walk-out last October, “work-ins” or events designed to make graduate student labor visible, and, most recently, a May Day demonstration with the University of Chicago Labor Council to push the University to recognize it. The walk-out was the largest escalation of GSU’s efforts for recognition to date and drew hundreds of graduate students and GSU supporters.

For Gonzáles, the decision to hold a strike vote reflects the union’s ongoing frustration with the University administration.

“We’ve sent countless letters, we’ve asked nicely many times to be recognized; the University has stonewalled us,” González said. “We’ve walked out; we’ve worked in; we’ve taken part in a solidarity demonstration with other unions on campus, and it’s abundantly clear that the University of Chicago will not recognize our union.”

Gonzáles said that a strike would demonstrate to the administration the value of graduate student labor. “We don’t want to go out on strike,” Gonzáles said, “but it’s become very clear that the way that this institution is going to recognize us is by us making them recognize how integral we are to making this place run.”

Despite their frustrations, GSU stated that any strike would be a last resort, arising only as the culmination of months of silence from the University. “The idea of not teaching my class really bothers me,” said Laura Colaneri, a GSU member and Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Romance Languages and Literatures. But, Colaneri is nevertheless convinced of the need to strike. “A strike seems to be the only way to convince University officials to recognize and bargain with GSU,” she said. “It’s the most powerful thing we can do at this point, to show them very directly how much the University relies on the work that we do and how it couldn’t operate without us.

When asked about what brought GSU to this point, many GSU members cited systematic problems in the way the University treats its graduate students.

Colaneri related a variety of concerns, from discrepancies in compensation packages among different academic departments, to payments that often arrive late or in incorrect amounts. Additionally, in her role as a workshop coordinator, Colaneri said she was not given any information about how much and how often she was to be paid for her labor, culminating in her not being paid for work that she began over the summer until the fourth or fifth week of the fall quarter.

“We can’t afford to not get paid until a month into the quarter,” Colaneri said. “When we’re doing work, we expect to be paid for it in a timely manner and at a reasonable rate.”

In response to a request for comment on the possible strike, University spokesperson Jeremy Manier did not address several of The Maroon’s specific questions, including how the University would respond to a strike and what, in the University’s view, triggered this most recent escalation. Manier’s full statement reads: “We have great appreciation for all that graduate students bring to the University’s intellectual community. The University is working directly with graduate students and faculty on many fronts to improve graduate education and quality of life.”

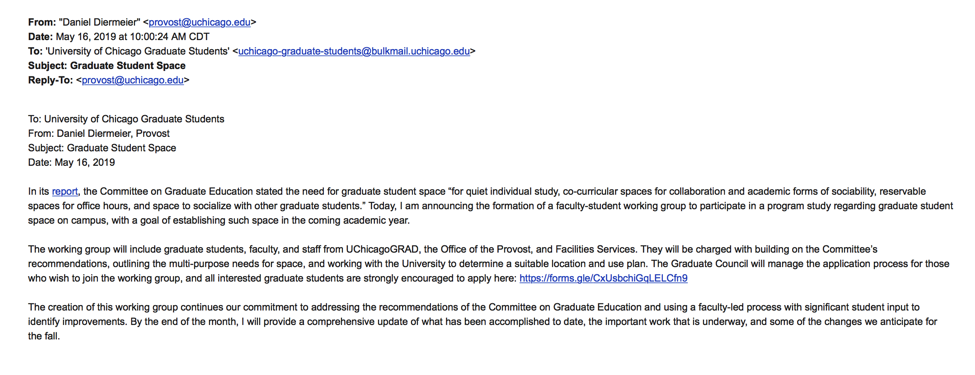

On Thursday morning, one day into voting, provost Daniel Diermeier sent graduate students an e-mail announcing that the University administration is forming a committee of faculty and students to look into creating more dedicated spaces for graduate students, citing the lack of space as a key complaint among many graduate students.

This announcement comes on the heels of Diermeier’s announcement earlier this month that the University will audit graduate student compensation this summer.

In both announcements, Diermeier referred to the recent publication of a report by the Committee on Graduate Education, a group comprised of faculty members and graduate students, that found increasing discontent among graduate students. In an April 10 response to the committee’s findings, Diermeier vowed to address several of the specific grievances cited in the report, including career support, funding, and compensation.

In interviews, GSU members said they were unswayed by the University’s recently unveiled plans. Evolutionary biology Ph.D. candidate and GSU member Natalia Piland told The Maroon, “I don’t see those committees being very effective and changing what the University actually looks like: The administration has complete power over whether to take the recommendations of committees or ignore them.”

By contrast, if the University recognized GSU, the administration “would be legally bound to implement the things that we ask for in a contract,” Piland said.

Colaneri added, “After I’ve been here for almost three years, they’ve started forming committees to say, ‘We determined that this pay thing was a problem’—and we’ve been telling them it’s a problem for years. A good solution for this is to recognize the union.”

Gonzáles concurred: “We do not want more focus groups, disempowered individual interventions, or hand-picked councils whose opinions are ignored whenever they are inconvenient.”