Quotes and attributions in this article, unless otherwise noted, are taken from minutes of the Council. The Council’s discussions are paraphrased in the minutes, and Council members vote at each meeting on whether to approve the previous meeting’s minutes. Speakers therefore have a chance to contest or revise the way their comments are paraphrased. Still, the minutes should not be read as direct quotes, or as perfect reproductions of conversations that took place. More information about the minutes and Council can be found here.

In 2011, a committee of faculty members was charged with studying master’s programs in the Humanities and Social Sciences Divisions (MAPH/MAPSS). The Wellbery Report, as it came to be called, was unequivocal in its findings: “in terms of both size and the quality of students, these programs had become a source of considerable and unacceptable strain.”

In response to the rapid growth, the committee unanimously recommended the University shrink the size of these programs.

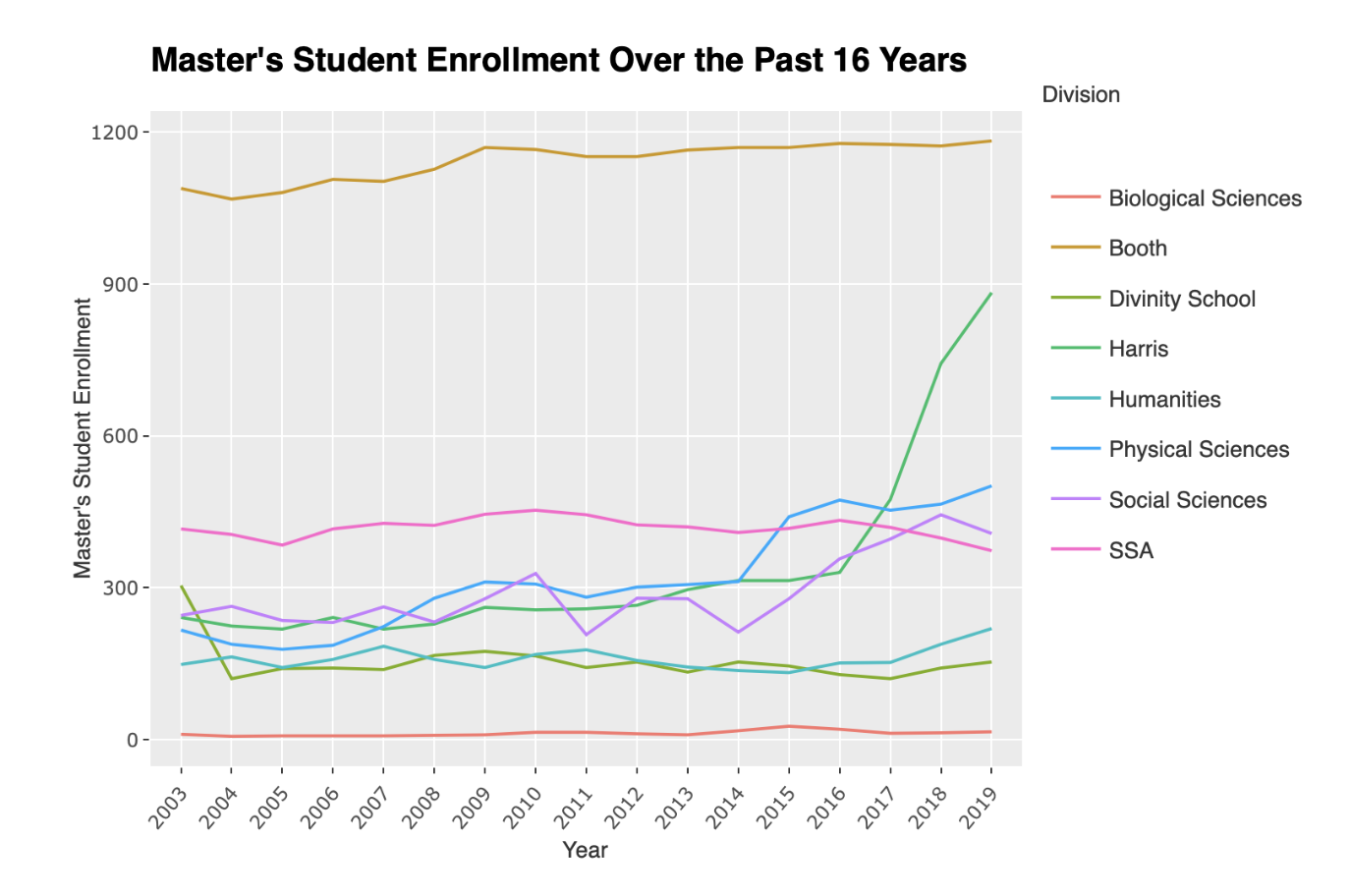

Nearly a decade later, the University has done the opposite. Since 2015, reports from the Office of the University Registrar show, master’s programs in the Social Sciences Division (SSD) have grown by 146 percent and those in the Humanities Division have grown by 165 percent.

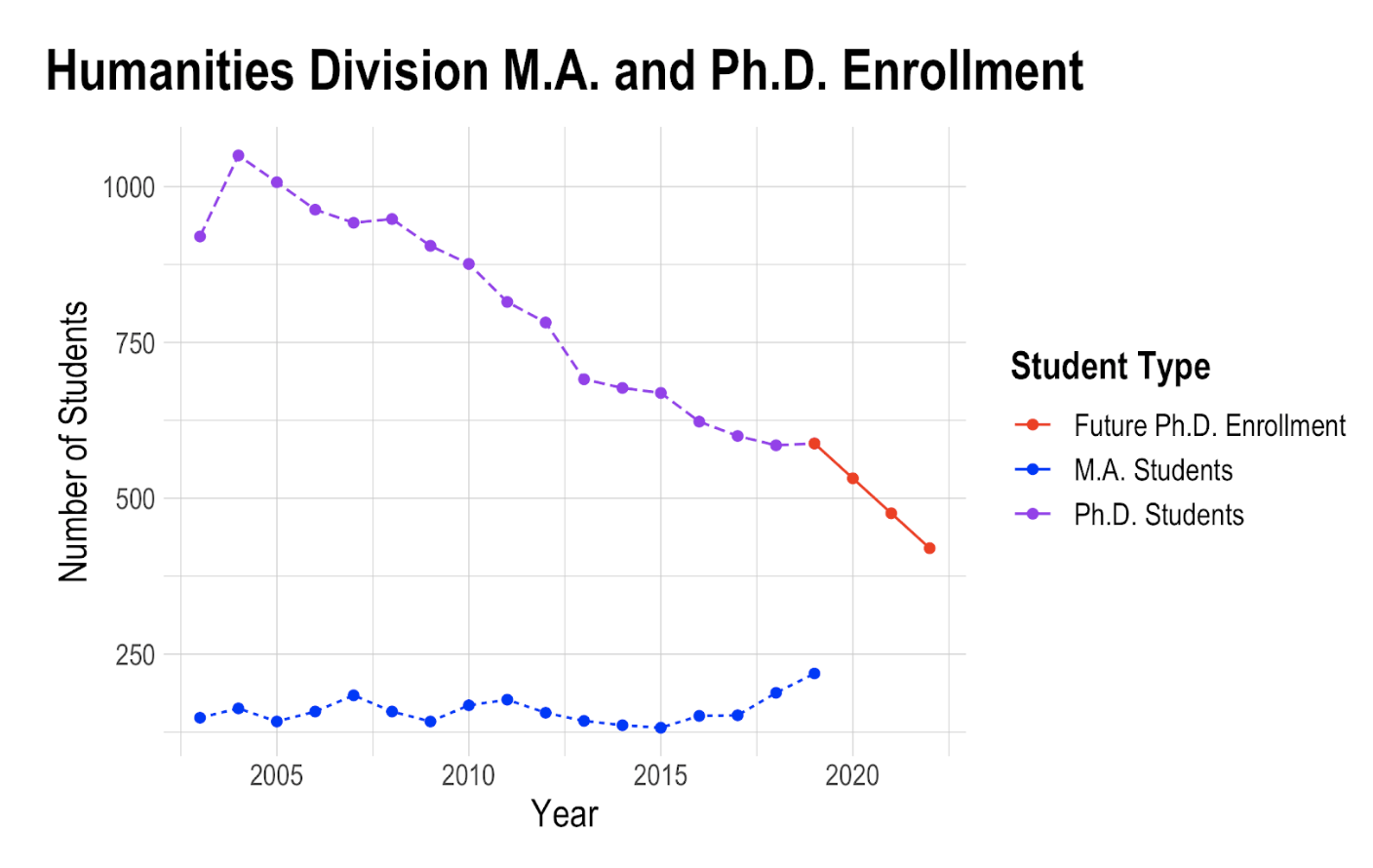

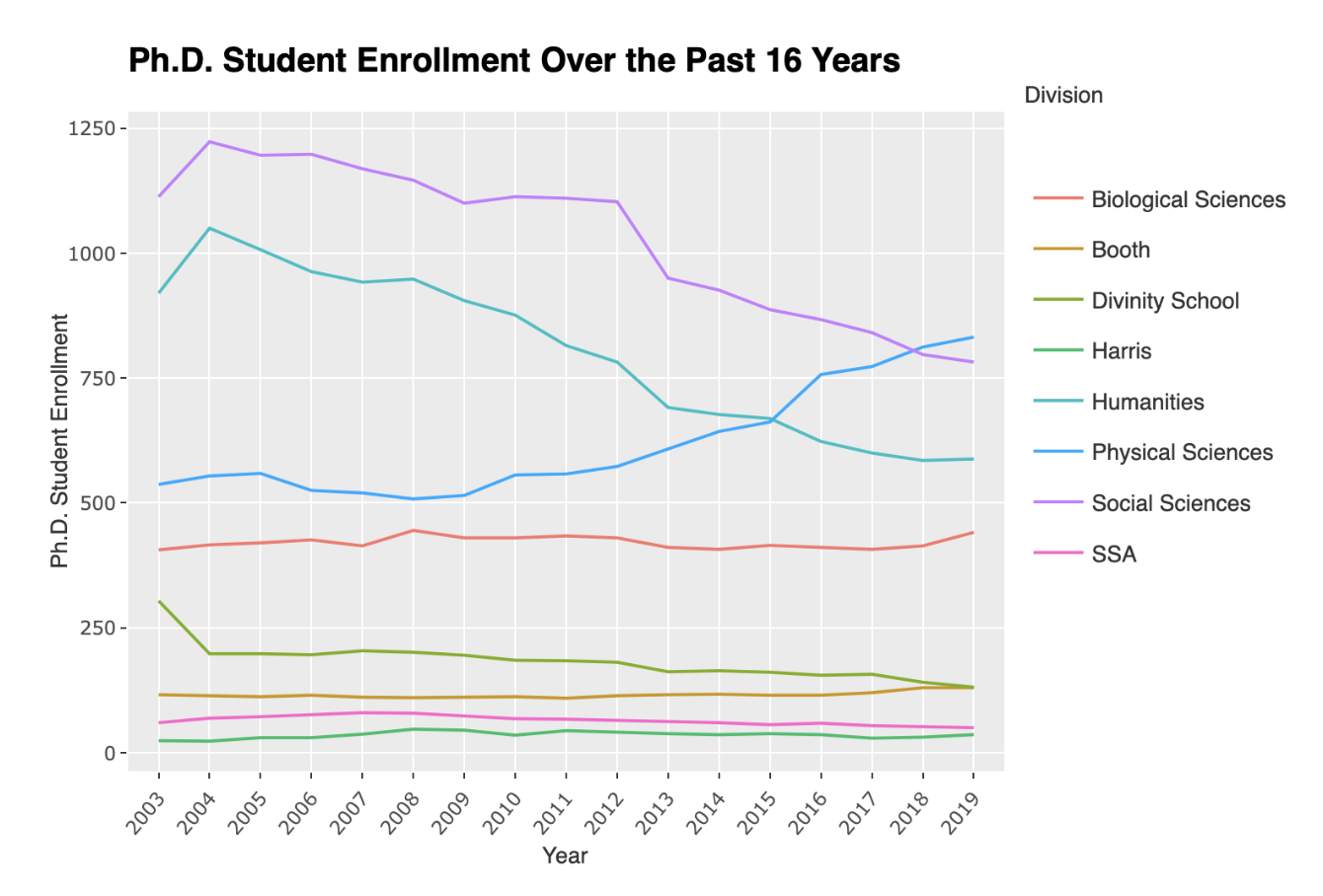

At the same time, doctoral programs in the two divisions have shrunk, with enrollment declining 12 percent in each—a trend that will continue with the University’s recent announcement that it will cap program sizes. In an internally circulated email among faculty, it was discussed that the administration planned to reduce the number of Ph.D. students to 420 by 2023. The opposite has been true in the Physical Sciences Division (PSD), where doctoral programs have grown by 145 percent.

These changes have occurred despite faculty members’ pushback. Last month, more than 100 professors signed a letter to administrators expressing concerns over the administration’s “top-down” decision to shrink the size of doctoral programs. Details from recently obtained faculty senate meetings and interviews with professors show that faculty members have also long been resisting the concurrent expansion of master’s programs.

Provost Daniel Diermeier has urged that master’s programs are one way the University can benefit from its improved national standing, and turn its “increased eminence into additional resources.”

But many faculty members argue the master’s programs have been pushed to expand at the expense of their quality.

“The real problem is that we are told that we have to admit a certain number of students,” English professor Elaine Hadley told The Maroon, referring to master’s programs. “We have to admit so many that we are often in a position where we take students who aren’t very well prepared.”

Master’s programs grow, against committee recommendation

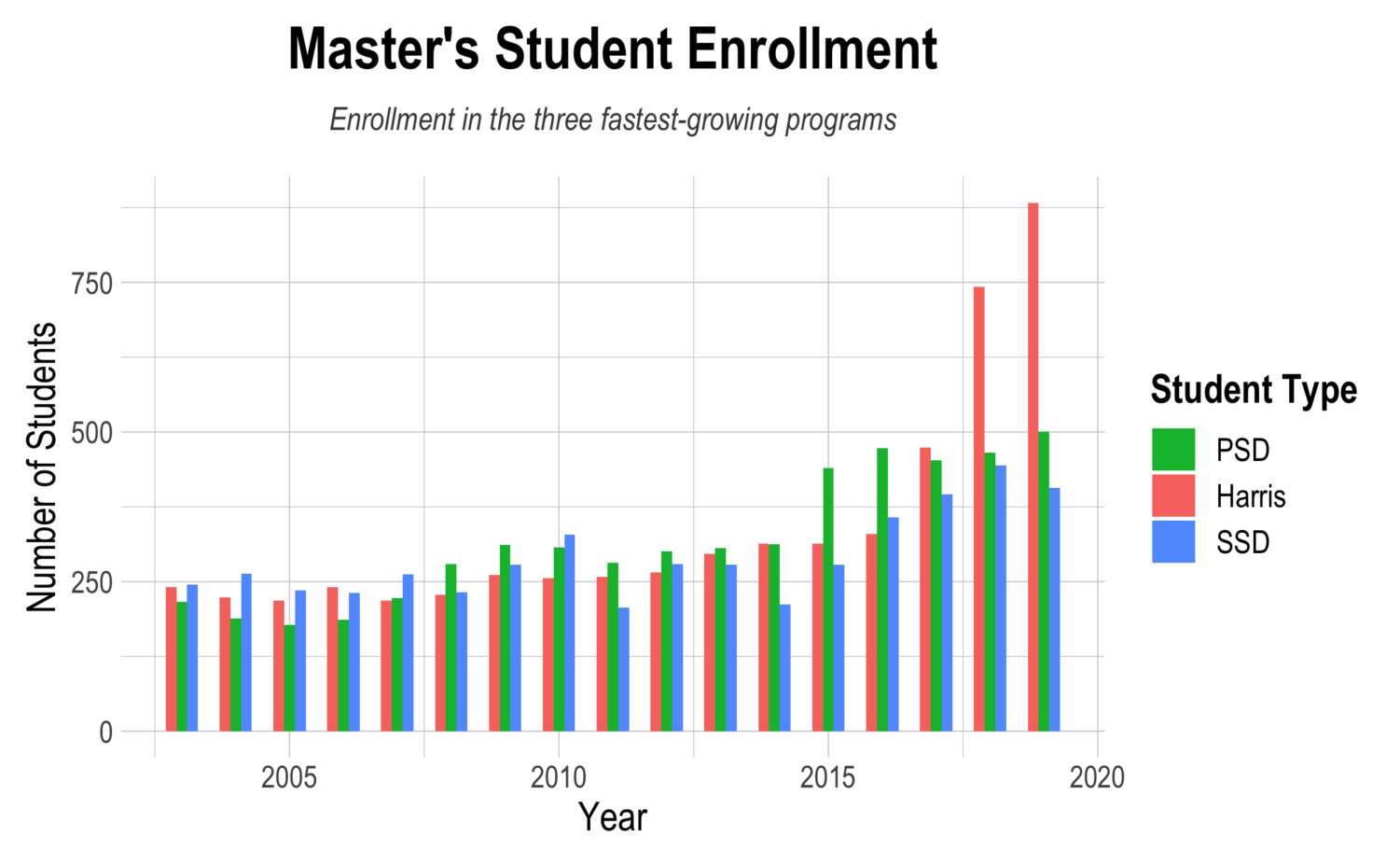

The Harris School of Public Policy has seen some of the most dramatic growth in master’s student enrollment—an increase from 330 to 883 students in five years, or a 168 percent increase.

According to Katherine Baicker, the dean of Harris, the school invested heavily in student recruitment efforts to maintain selectivity and facilitate its growth.

Baicker said in January 2019 at a faculty senate meeting that Harris had begun using strategies employed by College admissions dean James Nondorf. Baicker said Harris wants “to grow the pipeline, identify those students who would be a good fit for the Harris School’s program, and strategically deploy scholarship resources in order to attract the most desirable candidates and generate the most impact.”

The growth that Harris has experienced wasn’t something the authors of the Wellbery Report could have predicted in 2011.

Authors of the report, charged by then-provost Thomas Rosenbaum, found that the humanities and social sciences master’s programs “play[ed] an absolutely essential role in the culture and graduate life of the University,” but ultimately had “caused serious stress among the faculty serving those programs,” according to the minutes of a faculty senate meeting in October 2011 discussing the Wellbery Report’s findings.

Beyond the difficulties caused by a growing student to faculty ratio, the committee said, “a consistent leitmotif was the difficulty felt by faculty in reconciling the conflicting pressures forged by an ill-prepared subset of M.A. students with the normal expectations of graduate level programs at the University of Chicago. This kind of tension or frustration has also been replicated on a more individual level in the context of thesis advising.”

Germanic studies professor David Wellbery, chair of the committee that authored the 2011 report, said in a subsequent faculty senate meeting that the committee had found “faculty dissatisfaction with the admissions process [for master’s programs], which [had] led some to adopt a skeptical view of [the program’s] intellectual legitimacy.”

He added that there had been “a tendency for some M.A. students to avoid courses that required special linguistic or other forms of deep preparation, and to gravitate towards offerings that were topically familiar or were more local in nature.”

In response, one faculty member asked whether the committee had considered a separate faculty for teaching master’s students. Wellbery explained that the MAPH/MAPSS program “was rooted in providing opportunities for student involvement with the University’s faculty, rather than with specialized instructors.”

Previous directors of MAPH had recommended that the optimal size for the program would be 75–100 students, Wellbery said. The size is currently 219 students.

Stipulating that “the committee did not consider it their task to solve the financial problem,” Wellbery said the committee acknowledged financial loss would result from shrinking master’s programs in the Humanities and Social Sciences Divisions.

At the Council meeting, professors discussed growing the College as a potential alternative source of funds.

The increased revenue from the College was attractive, they said, since “the impact associated with a small increase in the number of undergraduates would be less onerous than the current situation.”

Lisa Wedeen, a professor of political science, noted that “the issue of teaching burden was impacted by quality considerations as well as quantitative adjustments, and therefore might not be fully addressed through the recommendation involving the size of the College.”

Master’s expansion as an alternative to “austerity strategy”

The financial appeal of master’s programs has persisted, comments from administrators in more recent meetings show.

In a December 2018 faculty senate meeting, when presenting an update on the University’s budget, Diermeier suggested master’s programs as a means of using the University’s reputation to draw in more revenue.

“He noted that the University’s endowment was one-fourth the size of Harvard’s, and on a per student basis, it significantly trails that of Princeton and Yale. He commented that this was a challenge that the University has faced for a long time, but the situation had been moving in a much better direction over the past few years. He also observed that in terms of the ratio between eminence and resources, the University was punching above its weight. He spoke of the challenge of translating this increased eminence into additional resources, and suggested several means of accomplishing this, involving master’s degree programs and offerings for non-traditional students, along with other types of opportunities. He added that he would much rather pursue this approach, rather than embarking upon an austerity strategy.”

Faculty members aren't all convinced that master's programs are worth expanding.

Wellberry recently told The Maroon that “the recommendation [in the 2011 Wellberry report] was based on the staffing and other resources at that time.” But, English professor Elaine Hadley said in an interview, problems outlined in the report are still present today.

Many faculty members feel “there has been a kind of numbers-driven, accounting-driven decision making practice around class sizes that hasn’t taken into account the intellectual and pedagogical environment,” Hadley said. “It’s the burden of that program having to generate revenue for the Division.”

Doctoral programs that rely on University funding continue to shrink

In the October 2011 faculty senate meeting discussing the Wellbery report, Near Eastern languages and civilizations professor Holly Shissler said while “advanced graduate seminars used to contain a preponderance of Ph.D. students,” the composition of her classes had noticeably changed.

She said she noticed “the balance has shifted, due in part to the expansion of the M.A. programs but also because of the shrinkage of Ph.D. cohorts, which has resulted in profound changes to the intellectual agenda of advanced classes.”

While MAPH and MAPSS have expanded rapidly in recent years, Ph.D. programs have shrunk. Since 2015, the SSD and the Humanities Division have seen a 12 percent decrease in doctoral student enrollment, while the SSD’s master’s programs have grown by 146 percent and the Humanities Division’s have grown by 165 percent.

The doctoral programs in the PSD are an exception, where doctoral programs have grown by 145 percent and master’s programs by 178 percent.

Diermeier’s comments at a faculty senate meeting last June revealed his thoughts on the relation between the size of doctoral programs at the Division level. Diermeier “felt it was a little misleading to talk about graduate education as a single matter,” and framed graduate education as falling into three distinct categories.

The Biological Sciences Division (BSD) and PSD, comprising the first category, face fewer funding concerns due to the abundance of external grants and philanthropic donations in their fields, Diermeier said.

The second category contains the mathematics, linguistics, and economics departments, which do not receive external grants, but in which time-to-degree falls within the five- to six-year range.

In the first and second categories, Diermeier said, all or nearly all “obtain jobs that are related to their fields of study, both inside and outside of academia,” he said.

Diermeier’s third category consists of the humanities, social sciences, and Divinity School. Students in this category have the longest time-to-degree, he said, also noting that the students face fewer job prospects after graduation and their departments have fewer funding opportunities.

Changes to doctoral programs recently announced by Diermeier will contribute to further shrinking. The provost announced in October that caps would be imposed on doctoral programs in the Humanities and Social Sciences Divisions, the School of Social Service Administration, and the Divinity School.

This decision was announced to faculty at the same time as the general public, deepening the perception among faculty that the administration does not take their input into consideration.

In professors’ internally circulated letter sent to Diermeier and Zimmer last month, in response to the new caps on doctoral programs, they expressed the intent of the letter was to “simply urge that a final decision about how to meet these challenges ought to have been the product of a real conversation between administrators and faculty.”

“The way in which these changes were decided and imposed strikes us as a betrayal of one of the basic principles by which we should operate.”

The discussion of the Wellbery Report by the faculty senate can be read below.