Quotes and attributions in this article, unless otherwise noted, are taken from minutes of the Council. The Council’s discussions are paraphrased in the minutes, and Council members vote at each meeting on whether to approve the previous meeting’s minutes. Speakers therefore have a chance to contest or revise the way their comments are paraphrased. Still, the minutes should not be read as direct quotes, or as perfect reproductions of conversations that took place. More information about the minutes and Council can be found here.

To Daniel Diermeier, collective bargaining is “a bad process.”

In meetings with the Council of the University Senate dating back to 2017, the University of Chicago’s outgoing provost has detailed his skepticism towards union negotiations, which he describes as an intractable mechanism leaving no room for nuanced solutions.

Diermeier frequently cites Harvard and Columbia universities, where graduate students recently unionized, as evidence that the collective bargaining process is an impenetrable snarl. At a meeting of the Council last year following a strike organized by Graduate Students United (GSU), Diermeier said that “there has been zero progress on anything that matters at Harvard and Columbia Universities.”

In arguing against graduate student unionization, Diermeier has billed himself as a defender of faculty interests—protecting the autonomy of the advisor-student relationship, and shielding heterogeneous departments against the intrusion of a union. “A collective bargaining agreement would likely create an environment of standardization without room for differentiation, changing the nature and scope of the relationships of graduate students to their advisors, other faculty, and degree programs,” he wrote in an email to the University last June.

Some faculty agree with Diermeier that a union would interject itself between professors and graduate students, creating a burdensome layer of bureaucracy. But a growing number of faculty members—including some critics of unionization—complain that the University was too aggressive in campaigns against GSU, and acted hypocritically in refusing to recognize graduate students’ election results after it had urged graduate students to vote.

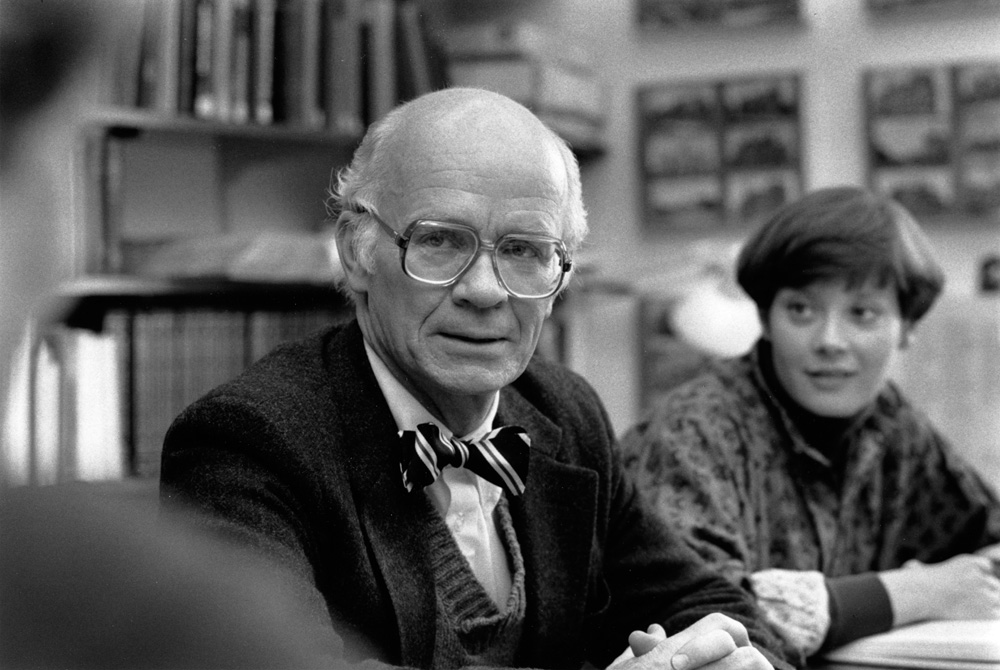

“I was not happy with the administration’s response. I remain unhappy with it,” philosophy professor Michael Kremer told The Maroon. “That’s true even though I am not a strong supporter of graduate student unionization.”

“There was a website put up by the administration to try to sway people to vote in the way the administration wanted,” Kremer said, referring to a now-defunct website called ‘Know the Facts.' “And when the vote did not go the way the administration wanted, then the administration did not recognize the results.”

Yali Amit, a statistics professor, told The Maroon that the administration’s campaign against unionization has damaged his view of University leadership.

“The graduate student unionization, for me, was kind of a breaking point where the discourse became so dishonest that I just don’t trust these people—the administration—anymore,” Amit said. “The fact that nobody among the deans, or the central administration, ever expresses any different opinion around this issue, seems to me to indicate that there’s a very strict policy—you can’t get out of line.”

Recently, other professors have raised questions about their lack of input in the broader question of unionization. The administration never sought a vote from faculty on GSU. But in a meeting last year, Council members asked whether they should have been given a say in whether the University recognizes the union.

Minutes of the faculty senate obtained by The Maroon give an unprecedented look at the administration’s thinking about graduate student unionization—and faculty pushback.

Does the University's response protect faculty?

At a Council meeting in April 2019, Diermeier praised the work of the Committee on Graduate Education, tasked with reviewing the state of graduate education, as “a faculty-led process with significant student input.” By contrast, he said, “if the University were to recognize the union, that process would stop, and be replaced by the highly regulated and legalistic process of collective bargaining.”

In Diermeier’s telling, part of the problem with the legalism of collective bargaining is that it would prevent faculty voices from being heard.

If the University were to recognize the union, he said at the April meeting, “the existing deliberations that were underway, regarding funding and the organization of graduate student programs, would have to stop, and these would be replaced by a collective bargaining process. At that point, the role of the faculty would end.”

At a meeting two months later, English professor Elaine Hadley argued that the faculty had “already lost control, because they have had virtually no input into conversations regarding whether the University should recognize the union.”

In interviews, professors echoed these concerns, saying that the administration’s unilateral response to graduate student issues did not arise out of discussions with faculty members. This was felt particularly acutely following the Provost’s announcement of a new funding model that will dramatically shrink the size of UChicago's Ph.D programs, which came as a surprise to many faculty members.

“The administration's single-minded obsession with GSU has had a more negative effect on the university's intellectual climate than unionized graduate students could possibly have,” political theorist John McCormick told The Maroon in an email.

“The new graduate student model is the culmination of this. They want to maintain the university's libertarian brand by preventing unionization even if this undermines, to my mind, a much more important part of our brand: the College. Having graduate students intern in the Core, TA in lecture courses and teach their own classes benefits everyone,” McCormick wrote. “But the vitality of the College is less important to Levi Hall than opposing GSU.”

“I think there were problems with transparency and consulting in the way the new system for funding graduate students was rolled out,” philosophy professor Robert Pippin wrote to The Maroon in a recent email.

While “there were both extensive divisional and university wide faculty committee investigations of the problem; all to the good,” Pippin said, “I don’t understand how these latter enterprises came to bear on, if they did, the formulation of the former, final plan.”

Early concerns over polarization

At a Council meeting in October 2017, professors anxiously discussed the mood on campus in the wake of the graduate students’ vote to unionize.

The provost opened his comments by saying that “the University is an institution that prides itself on its commitment to graduate education, and yet over 1,100 students had, through this vote, registered their unhappiness and feelings of being disrespected.”

To Diermeier, “regardless of one’s views on the specific issue of graduate student unionization, this was an extremely troubling outcome.”

David Nirenberg, then Executive Vice Provost, described the unionization effort as an “adversarial process” in which “the faculty have been very respectful towards graduate students, and there has been no use of dehumanizing or disrespectful language,” whereas he had not “always felt similarly respected in return.”

Erin Adams, a biochemistry professor, also argued that graduate students’ treatment of administrators had been polarizing, and said she thought “the administration had taken a position that it would naturally take,” while “the faculty had been mostly left out of this process,” and it was “students against the administration.”

All present seemed to agree that the present situation was troubling. Several professors, though, felt it was troubling for reasons different from those cited by the administrators and Adams.

Some faculty at these early meetings complained of what they described as aggressive anti-unionization campaigns by the administration. One professor said she was aware of thirty students who had at first been ambivalent towards unionization, but who had been “so taken aback by the administration’s hardline positions that they had reversed their stances.”

Disavowal of the union vote

Faculty took issue not only with the University's aggressive campaigns against GSU, but also with its move to ignore results of the graduate students’ election.

At the October 2017 meeting, Council members pressed University attorney Ted Stamatakos to describe the path the University would take going forward. Stamatakos outlined a number of legal avenues, including refusal to bargain.

At a meeting the next month, Kremer said he “could not think of something that would be worse than having the University refuse to bargain with a legally certified union.”

Cliff Ando, a classicist, pushed back against others’ suggestions that the election had been a protest vote, observing that “graduate students have been agitating for unionization for over a decade, and that the election turnout had been quite high.”

At a January 2018 meeting, public health professor Harold Pollack said that although he had concerns about unanticipated effects of unionization, he doubted “that the University could oppose the union and command a widespread sense of process legitimacy at this point.”

By the time graduate students went on strike in 2019, many faculty shared concerns about how the administration could retain legitimacy while facing down a union campaign with popular support.

At a special Council meeting following the strike, English professor Kenneth Warren described an email from the administration regarding GSU’s decision to withdraw its petition from the National Labor Relations Board as giving an incomplete picture of the situation. Warren recommended that “the administration admit to its own tactical maneuvering.”

Echoing arguments made over the previous two years, several faculty members argued that central administrators had misled graduate students by refusing to bargain with them in 2017, following the vote.

Anton Ford, a philosophy professor, recalled that administrators urged graduate students to vote in the 2017 election. To Ford, this had been “a significant process of public deliberation on this campus that had been endorsed by the administration as being legitimate,” and was subsequently ignored when students voted for a union.

“He then referenced an email from then-Executive Vice Provost David Nirenberg that had concluded with an urging for all eligible voters to vote, and had conveyed that “your voice truly matters’. He recalled that two days later, the graduate students overwhelmingly voiced their opinion. However, this was not treated as if it was an element of the decision-making process. Rather, it was regarded as a poll. He found this to be quite appalling, and he did not believe that this should be shunted aside.”

Ford suggested that the University could have responded differently, pointing to Harvard University, which agreed voluntarily in 2018 to collectively bargain with its graduate student union. Columbia University agreed to commence bargaining with its union later that year. In response,

“Mr. Diermeier observed that there has been zero progress on anything that matters at Harvard and Columbia Universities. He offered examples of the types of the issues [sic] that are front and center at those institutions, including Title IX, the use of third-party arbiters, and sanctuary campus status, and stated that these have nothing to do with improvements to graduate student life. He did not view those institutions as serving as suitable role models for what the University is seeking to accomplish.”

English professor Zachary Samalin attempted to redirect the Provost to Ford’s comments.

“Mr. Samalin noted that Mr. Diermeier’s response was not relevant to the substance of Mr. Ford’s remarks, which had been about the disavowal of a valid process that the University itself had solicited.

Mr. Diermeier replied that the University had previously made its position quite clear, in presentations to the Council and in writing, that it was contesting the legality of the election.”

Later in that discussion, Kremer described the negative consequences of continued failure to recognize the union. “His sense was that from the graduate students’ point of view, they had been lied to.”

Other professors worried that administrators had dealt lasting damage to relationships between graduate students and their advisors. The unilateral handling of the issue had soured faculty-administrative relations as well, they say, needlessly alienating professors who had been broadly sympathetic to the administration’s goals.

Citing Ford’s comments on the issue of the legitimacy, sociologist Elisabeth Clemens asked about the administration’s “alternative theory of the legitimacy of a non-union response,” noting that “what has transpired so far may have been tone-deaf to optics.”

Gabriel Lear, a professor in the philosophy department, seconded Clemens’s point, critiquing “the administration’s claim that students would be part of the decision-making process, which had not happened.”

“While [Lear’s] own view was that unionization was a bad idea, she agreed that it was problematic that this claim had been made.”

A solution to dubious “process legitimacy” – poll the faculty?

One solution, some said, would be a vote to ‘poll’ the faculty.

Neuroscientist Daniel Margoliash, who told The Maroon he believes unionization is a bad idea, felt faculty members should nonetheless be able to make their views known in the question of whether the University recognizes GSU.

Margoliash last year suggested to the faculty senate that faculty should be polled on their support for unionization. This would be “a brave step to take,” he told the Council, since it is “unknown as to how the results would turn out.”

Lear also “raised the possibility of polling the faculty, to find out whether they wish to think of their students as workers.”

Christian Wedemeyer, a historian of religion, argued that a faculty vote is not only desirable but required. He cited debates in 2012 over the legislative authority of the Council, during which the deans had concluded:

“… a fair reading of the Statutes indicates that the Council’s legislative powers involve the educational work of the University – specifically those matters that relate to the teaching activities or functions of the University and which either (1) affect more than one Ruling Body or (2) which substantially affect the general interest of the University.”

Wedemeyer “then highlighted Mr. Diermeier’s earlier statement that the graduate student unionization question was an educational matter, i.e. one relating to teaching.”

Based on the administration’s own interpretation of the University Statutes, “it seemed very clear,” Wedemeyer said, that “the final arbiter of whether the union should be recognized was the Council of the University Senate.”

Diermeier directed Wedemeyer to the report of a committee chaired by philosophy professor Robert Pippin, produced around the same time as the deans’ report Wedemeyer cited, which had argued for a narrow interpretation of the Council’s authority.

Questions of governance were “a separate conversation” from the issue of unionization, Diermeier said. He suggested that this discussion take place in the future, with Zimmer present.

Pippin, in a recent email to The Maroon, wrote that he thinks the question of graduate student funding is not the exclusive purview of the central administration.

“Financial aid to graduate students is a matter that concerns the resources of the university, its level of indebtedness, commitments already made to future capital projects and fund-raising probabilities. This would seem to make the issue primarily an administrative one,” Pippin wrote.

“But how graduate students are funded, by how much and for how long, has profound consequences for the educational mission of any graduate program,” Pippin went on. “So this is an issue that should be the subject of extensive collaboration between the ‘financial’ and the ‘educational’ representatives.”

Current members of the faculty senate who would like to see more consultation on the union question aren’t holding their breath.

“We don’t have the right to advise the administration on matters of real importance to the structure of the university,” Anton Ford told The Maroon in a recent interview. “It’s a bit absurd. It appears that the primary function of this body is to provide democratic cover for the administration to do whatever it wants.”

In the next article in this series, The Maroon looks at the Council’s discussions of GSU in more detail. Faculty senate minutes discussing unionization can be read here.