When Anna Katz received her letter of acceptance to the University of Chicago in December 2019, the term COVID-19 did not exist.

“I definitely was thinking ‘Oh, I’ll be on campus, things will be normal’ when I first got in,” she said.

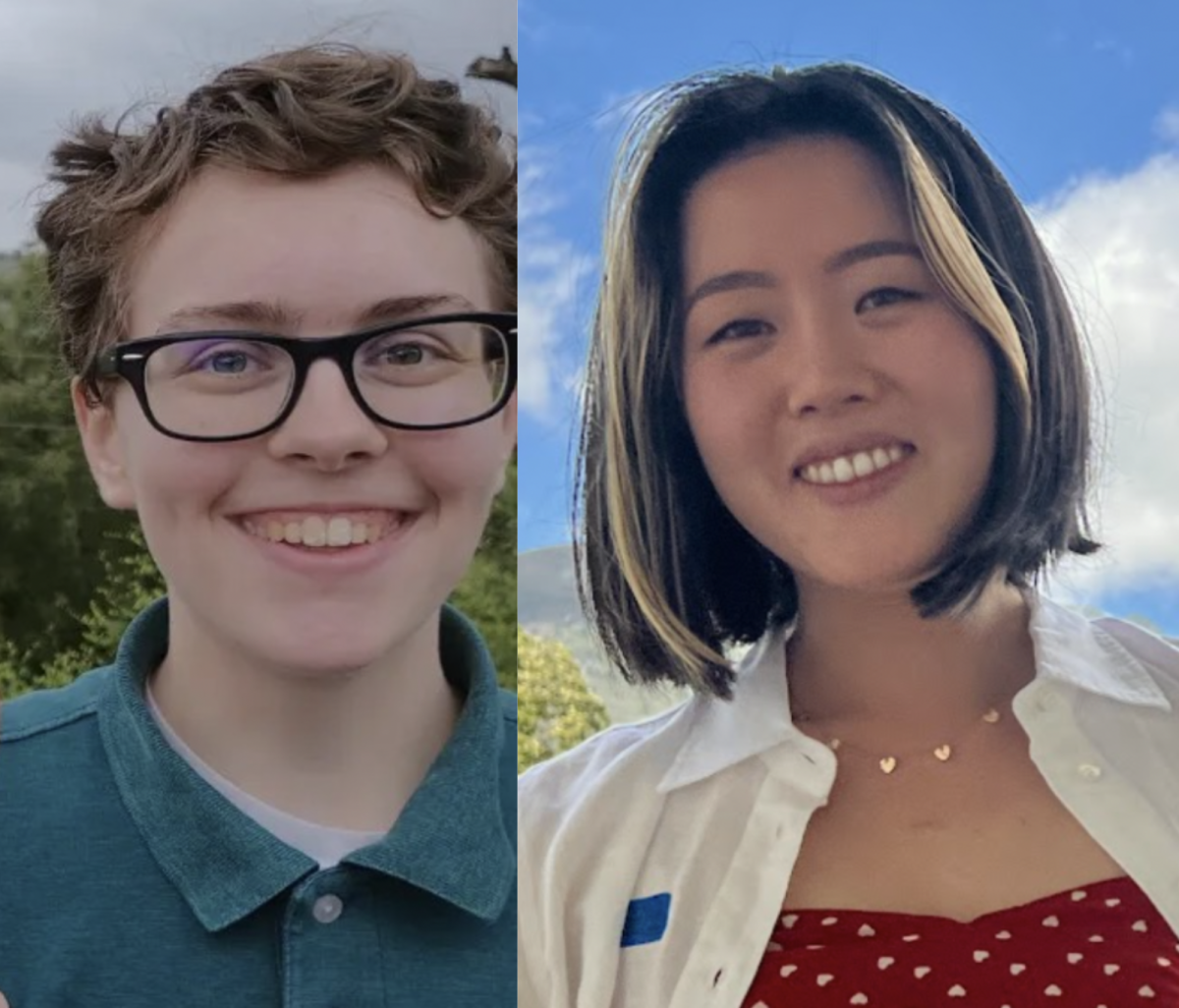

But those expectations of life as a first year have since been shattered as the COVID-19 pandemic has changed the way the University operates. While students of all class years have been allowed to return to campus, the majority of traditional offerings, including classes, Registered Student Organization (RSO) meetings, and O-Week programming, have gone virtual. “Most of it, like 99 percent, has been online,” said Evan Cholerton, a member of Rickert House in Max Palevsky Residential Commons.

The shift to remote programming is perhaps most pronounced in student coursework. Autumn quarter classes are offered in three formats: fully virtual, fully in-person, and a mix of both. Students whose classes have in-person components have had to adapt to the new protocols of mask-wearing, sanitation, and social distancing.

Lucas Mantovani’s calculus class, which meets three times a week, is one of those fully in-person courses. “It’s interesting to be six feet apart from people in a classroom,” he said.

The additional safety measures, however, have not deterred students from taking in-person classes, according to Joseph Chasnoff, whose hybrid-format Russian course meets once a week in Rosenwald Hall. “We’re doing a really good job of making sure everyone feels safe and comfortable having an in-person class there,” he said.

Even in online classes, professors have found ways to engage those living in Hyde Park. During one class period, Katz’s Civ section took a field trip to the Fountain of Time monument, located at the western end of the Midway. “That was a pretty cool experience because in that class we’re studying heritage and how that was shaped,” she said. “It was like the only time I’ve met my professor in person or seen the class in full scale.”

But remote courses have not been trouble-free, with some students observing that the natural flow of conversation in discussion-based classes has been hindered. “Just having to press the unmute button to speak, it’s very prohibitive,” Chasnoff said. “It really stifles discussion and learning from your peers.”

Also missing are the opportunities to chat with classmates before and after class. “It’s definitely trickier to make friends through Core classes this year, especially the online ones. You can't talk to people right after class as you're walking back to your dorm or to the library,” Cholerton said.

As such, students have to find their community in alternative ways. Cholerton heard about classmates who befriended each other on the elevator rides to their dorm rooms. Katz mentioned that many friendships formed before students arrived on campus, through shared past experiences and social media group chats created over the past few months.

The restrictions have also made it difficult for new students to engage with house culture. Chasnoff, a resident of Boyer House, lamented the “one-dimensional” nature of a dorm experience without house lounges and other spaces. “That was something I was really excited for, the house tables and getting to interact with the people in the house, […] and that hasn’t really existed this year,” he said.

In the newly built Woodlawn Residential Commons, residents face the additional challenge of building house culture from the ground up. “We don’t have any traditions, we have never had any leadership, so everything is kind of being formed by this first group,” remarked Maxwell Jones, who lives in Gallo House.

With inside gatherings curtailed, students find themselves going outside to meet classmates. Mantovani, who lives in Max Palevsky, observed that friendships are often determined by residence hall location. “Most of your friends will probably be from Max P or North because when you’re grabbing something to eat, those are the people you’ll see all the time,” he said. “And when you go to South and Woodlawn and [Burton-Judson] it looks like you're meeting totally different people.”

As a result, students have formed small “bubbles” for eating together and socializing. “It’s like your ‘family’ in a sense. People you eat with, obviously, kind of becom[e] your smaller circle,” Jones said. “And I think that’s a healthy pattern. I think it should be encouraged more.”

Students have also had to adjust their studying routines, since the libraries only accommodate a limited number of people. Although he mostly studies in his dorm room, Jones managed to secure spots at both the Mansueto Library and the Harper Memorial Library. “It was great, but you can only get slots for an hour or two,” he said. “Once you actually get in the zone, it’s time to leave.”

Despite having limited access to buildings, many students still enjoy roaming around campus. Katz, a resident of International House, has walked “to every corner of campus many, many times.” But since her residence hall is located several blocks from the quad and most other University buildings, she admits she explores campus more than most. “If you live in a dorm where the dining hall is right below your room, it’s very easy to stay in that area,” she said.

Students are also exploring locations in the city of Chicago. “A lot of people go to the museums or Chinatown or Wicker Park. Those seem to be pretty popular places,” Katz said. So is Promontory Point, although Jones noted that fewer students have been going there as the weather cools.

Not everyone has ventured off campus, however; since the quarter started, Mantovani has not left the Hyde Park area. “It also depends on what your major is and what you want for your future,” he said. “Because if you’re more oriented to research or STEM, you’re probably going to do activities that basically leave you alone for longer.”

Given the circumstances, students appreciate the opportunity to live and study on campus. “I’m super grateful to be here,” Cholerton said. “A lot of people don’t have a stable life at home, they don't have the resources, and being on campus is a good way to provide that.”

The UChicago experience—and indeed the first-year college experience—may look drastically different for the Class of 2024. Yet for Katz, who could hardly have imagined a global pandemic when she opened her acceptance letter ten months ago, coming to campus remains the right decision. “I'm very glad I didn't take a gap year. I'm very glad I didn't go remote this quarter. I don’t regret this.”