On Wednesday, February 12, a group of Chinese graduate students organized a memorial service to honor the late Li Wenliang, a whistleblower for the COVID-19 outbreak in Wuhan, China, who died of complications from the virus on February 7. The vigil took place at Bond Chapel, and over 100 people in the University and Hyde Park community attended.

Li, an ophthalmologist at Wuhan Central Hospital, was among the first to spread the word online of the SARS–like virus spreading in Wuhan before the Chinese government released any information. In early January, he was disciplined at work and by local police for promoting “untrue speech.” On February 7, Li died of COVID-19, which he contracted while treating a patient who was later diagnosed as positive. By then, Wuhan had been locked down for two weeks. The death of Li triggered widespread mourning among Chinese communities around the globe.

The group of students organized the vigil for Li on February 12, five days after Li’s death. In traditional Chinese belief, this day, called “Tou Qi,” is thought to be the day when the spirit of the deceased revisits its home.

“I was inspired to organize this after I saw the news about a vigil at Central Park in New York City,” explained a Ph.D. student of comparative literature who wished to remain anonymous. “I was angry and sad when I received the news of doctor Li’s death, so I wanted to do something.”

She posted about the idea of holding a vigil in Chicago on Douban, a Chinese social networking site; the post was soon censored and removed. She then decided to organize a vigil on campus with several other students.

During her introduction of Li, another student who hosted the event commended his courage to continue speaking to the public after being forced to sign a police document admitting that he had committed an “illegal act.”

“Doctor Li told us that a healthy society should not only have one voice,” she said.

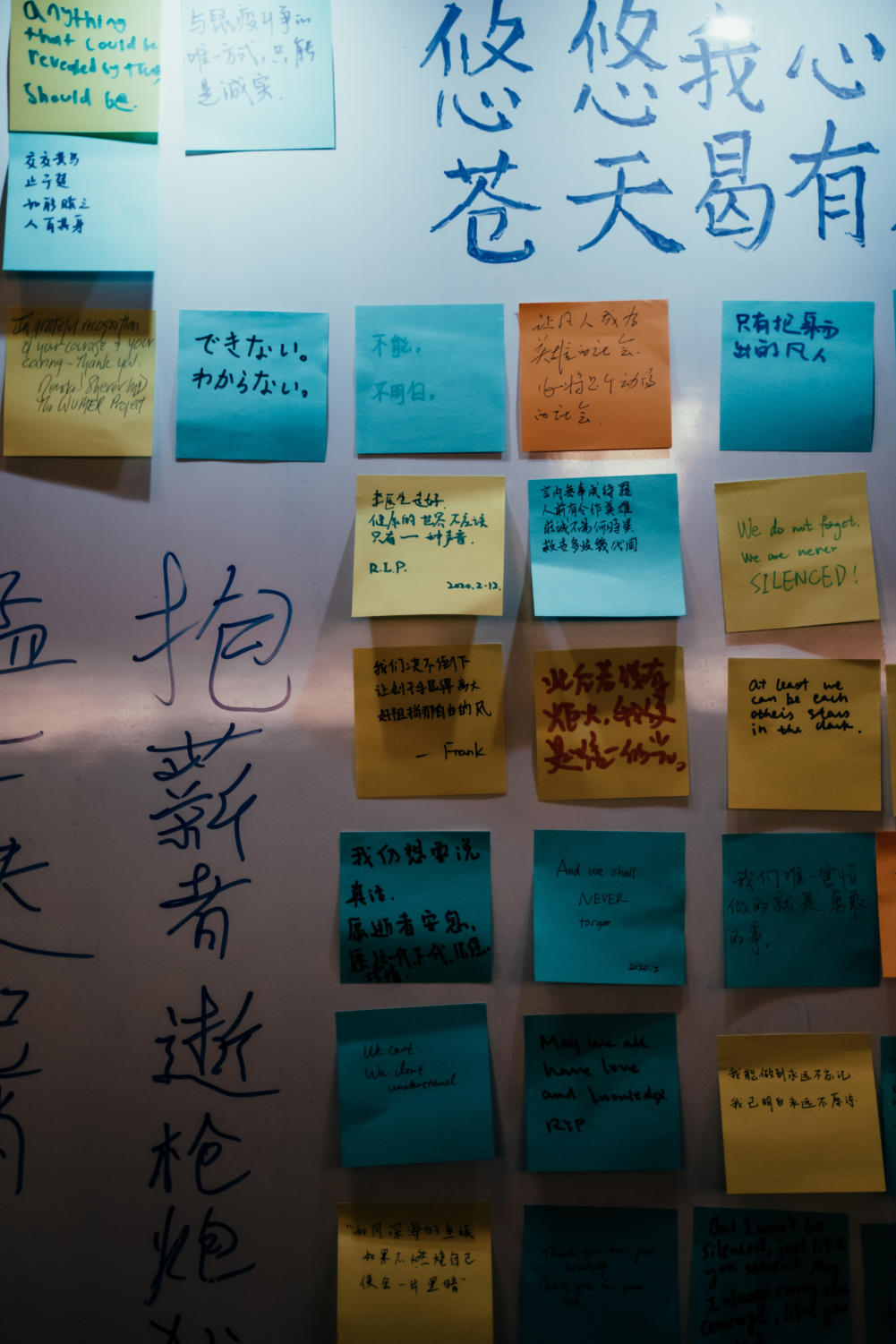

The audience read the poem “The Answer” by Bei Dao together. The poem is well-known among Chinese audiences for its defiant language against the Cultural Revolution’s civil restrictions. The group then mourned in silence for one minute.

A second-year Chinese student in the Master of Arts Program in the Humanities (MAPH), told The Maroon that her motivation for coming to the vigil was more than just about memorializing Li’s death. “I think there’s a responsibility that comes with being a citizen. If you believe that free speech is important, and if you think that the government could have done a better job during this kind of event, you would come to this vigil.”

“The outbreak of coronavirus will completely change the lives of many, including my own. I don’t want to call Li a hero, but he’s an ordinary person who we’ve seen and understood in this revolutionary period. I wanted to remember him in my own way,” another MAPH student added.

Benjamin Ross, a Ph.D. student in the sociology department, said he was interested in people’s response from a social-movement perspective. “It is an interesting historical moment, because Chinese people are very angry,” Ross said. “You can see the huge response in social media. Meanwhile, the most fruitful thing that comes out of these activities is that you connect with people who have similar beliefs with you.”

One of the organizers was a MAPH graduate who worked part-time on campus and who wished to remain anonymous. Before the vigil, he had assisted with relief efforts for the outbreak by collecting information about nonprofits, civil society, and individual donors.

“I finished doing that a week ago. This week, I felt helpless as I faced the news about the outbreak until I heard about doctor Li’s death,” the organizer said. “I felt that it was something I could do. I didn’t think too much of it; I think that most people don’t think too much when they’re responding to huge events or disasters.”

“We had originally planned to hold the vigil outside Regenstein Library,” he added. “We hoped that more people would be able to see and learn about the cause, even if they hadn’t kept up with the news.” The vigil was moved to Bond Chapel due to snowy weather.

The day after the vigil, Li’s framed picture, along with candles and flowers, was moved to an area in front of Regenstein Library.

Sociology professor Dingxin Zhao used the vigil to reflect on the tense relationship between the Chinese people and their government. In an interview with The Maroon, Zhao said, “Li was not a whistleblower. He only warned his friends in private messages. He became a hero in the minds of people because we, as a society, needed a hero amid our overwhelming fear of the coronavirus.”

Zhao pointed out that while many other significant people have died of the virus, only the death of Li has generated widespread outrage. “The sad thing that our memorial of Li has reflected is the distrust between the people and the government,” he said. “The Chinese people have never fully trusted their government, and this distrust has now reached new heights.”

Before he left the memorial service, Zhao wrote a note on the message board, which read: “A society that makes an ordinary person a hero must be an unstable society.”