For students with disabilities, the transition to self-isolating or quarantining under the current circumstances is not unfamiliar, but still presents challenges. With the University’s switch to remote learning, accommodations that students with disabilities have requested in the past are now commonplace in the virtual classroom.

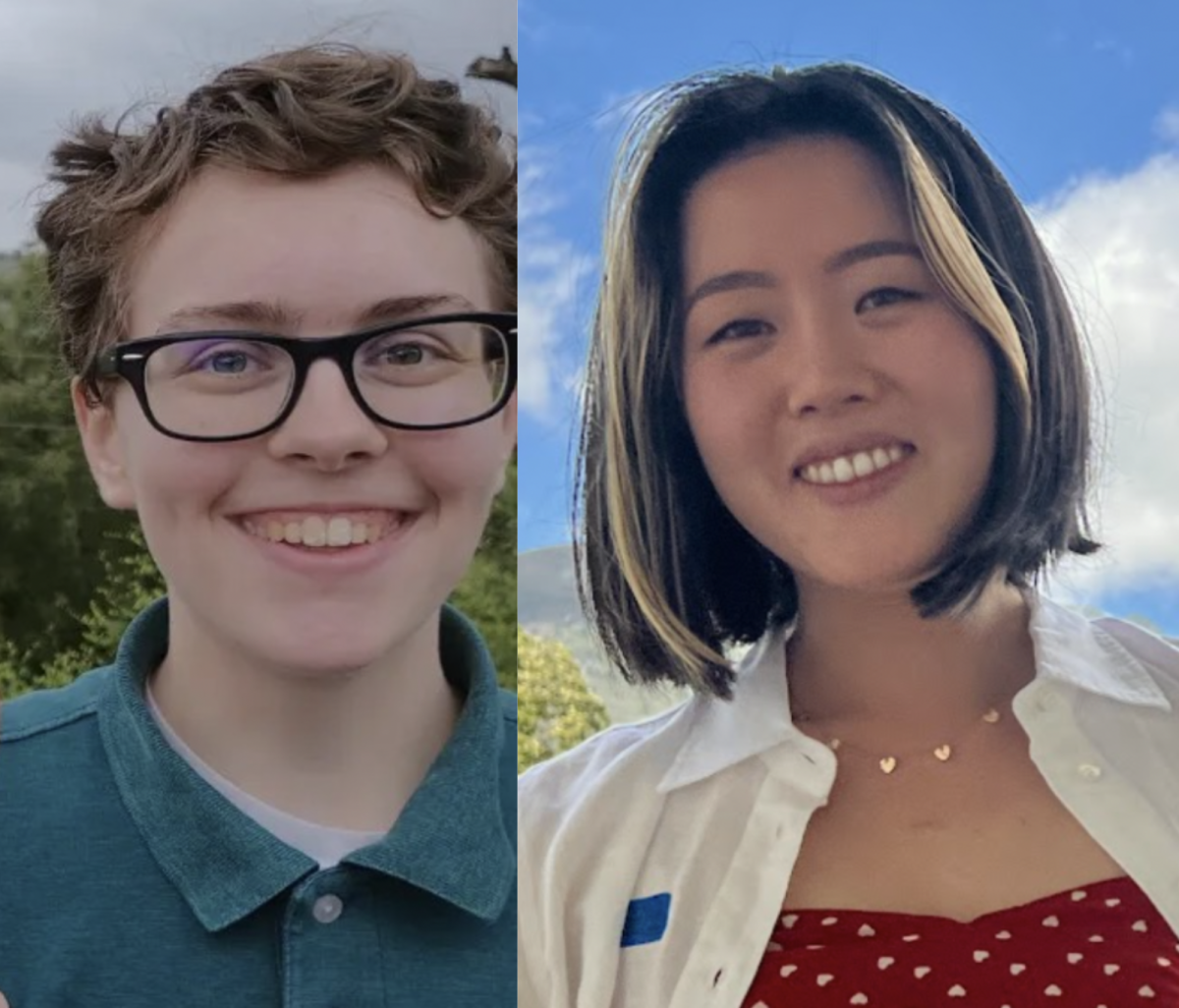

Brittney Dorton, a fourth-year undergraduate, and Beth Karp, a fourth-year at the Harris School of Public Policy and the Law School, serve on the University’s accessibility advisory board. Dorton is also an organizer of the Organization for Students with Disabilities (OSD). According to them, remote learning offers relief from the inaccessibility of campus and normalizes the physical and emotional isolation that being disabled often brings.

“Most people [with disabilities] have had a period in their life where they have had to either be isolated or quarantined for a month if not longer,” Dorton said. “So, for a lot of people, this is better [than usual] because they’re not the only ones doing it…. When you’re disabled and you’re isolated by yourself, it’s really lonely.”

However, COVID-19 also poses a unique health risk for disabled and chronically ill people. Not only are they possibly at a higher risk for contracting the disease, but the pandemic has also overwhelmed hospitals, limiting their access to the ICU should their condition bring about a medical emergency.

The barrier to accessing therapeutic services, including physical, educational, and behavioral therapy, has also posed a challenge for people with disabilities.

Dorton uses Student Counseling Services and receives physical therapy regularly for her disability. Both have transitioned to teleservices. Dorton’s physical therapy provider offers video sessions, where a therapist coaches her through home exercises, but she says the quality is diminished without hands-on coaching.

More concerning, Dorton said, is the lack of access to technology and procedures that physical therapy offices and medical centers typically provide. Dorton receives a spinal injection every three months to manage chronic pain, but since health services have been overwhelmed, her procedures have been indefinitely canceled.

“For me, it’s more of a quality of life thing, but there’s definitely people who have a treatment they need in order to survive, and it’s a scary time not knowing if you’re going to get it or not,” Dorton said.

As many health challenges as COVID-19 has posed, Dorton and Karp both highlighted the academic benefits it has brought for students with disabilities. Virtual learning has provided the flexibility of recorded classes, either to make up a class missed due to illness or to playback a class more than once for those with learning disabilities. It also lifts the burden of having to physically navigate an inaccessible campus.

However, “disability is funny because it’s a really big tent…. One person’s accommodation can be a disadvantage to another disabled person,” Karp said. She mentioned the challenges of looking at a screen for certain disabilities, and how virtual classes might make it more difficult for students with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) to focus during class.

For other students with disabilities challenged by remote learning, including deaf and blind students, technology has in some ways aided the transition, according to UChicago’s Student Disabilities Services (SDS).

In an emailed statement to The Maroon, SDS wrote that “Students with approved academic accommodations are able to access resources such as note-taking support, recordings of course content, alternative text and document conversion services, and interpreting and captioning services as appropriate. A number of these accommodations are integrated directly into the Zoom platform. Exam accommodations have been incorporated into Canvas and typically take the form of additional examination time.”

The University has also recommended certain accommodations and considerations for teaching students with disabilities. However, it is at the discretion of individual instructors to grant them to students, unless mandated by a student’s personal accommodation letter. These considerations include closed captioning lectures, audio descriptions of visual displays, and keyboard accessibility functions.

Dorton and Karp recognized the resources the University has provided students. However, according to them, this also highlights that the University’s past resistance to accommodate students with disabilities in these ways seemed to be not a matter of resources but discrimination. “Having [these resources] now is nice, but it’s also a feeling of, why couldn’t this happen before?” Dorton said.

“There are a lot of people with disabilities who have asked for these kinds of things in the past as accommodations…. For years we’ve been told, ‘No, that’s not possible. You just can’t learn that way. It’s not the same.’ And, now, suddenly, it is possible for everybody to do it and everything is moving to this. We had that capability all along; people just didn’t want to make those accommodations,” Karp said.

According to Karp, some students have previously been granted the accommodation of recorded lectures, while others have been told lectures will not be recorded as an accommodation under any circumstances. In the past, Karp has also been denied a dial-in option from student groups.

When Karp received her updated accommodation letter from the University a few weeks ago, it included two sections: one for virtual learning and one for normal classes. Both Karp and Dorton want the accommodations that have been granted for remote learning to continue when the University returns to campus.

Karp and Dorton additionally wish that, as the University becomes comfortable with the remote technologies that students with disabilities have previously requested, it will be more likely to offer them as accommodation in the future.

“I just hope that, at the end of all this, people will keep in mind that we all benefit from a more accessible world. There’s literally no downside to having classes that can be Skyped into or being able to record lectures,” Dorton said. “Having all those measures in place benefits disabled students and benefits a student who needs to go out on a job interview for a day, or a student who loses a parent, or a student who’s sick with the flu.”

“And I hope that more people will come out of this with more empathy for what disabled students and disabled people go through because our lives, all the time, revolve around periods of isolation…. So, everything that people are living through now is kind of the norm for disabled and chronically ill people,” Dorton added.