There are no fraternities at the University of Chicago.

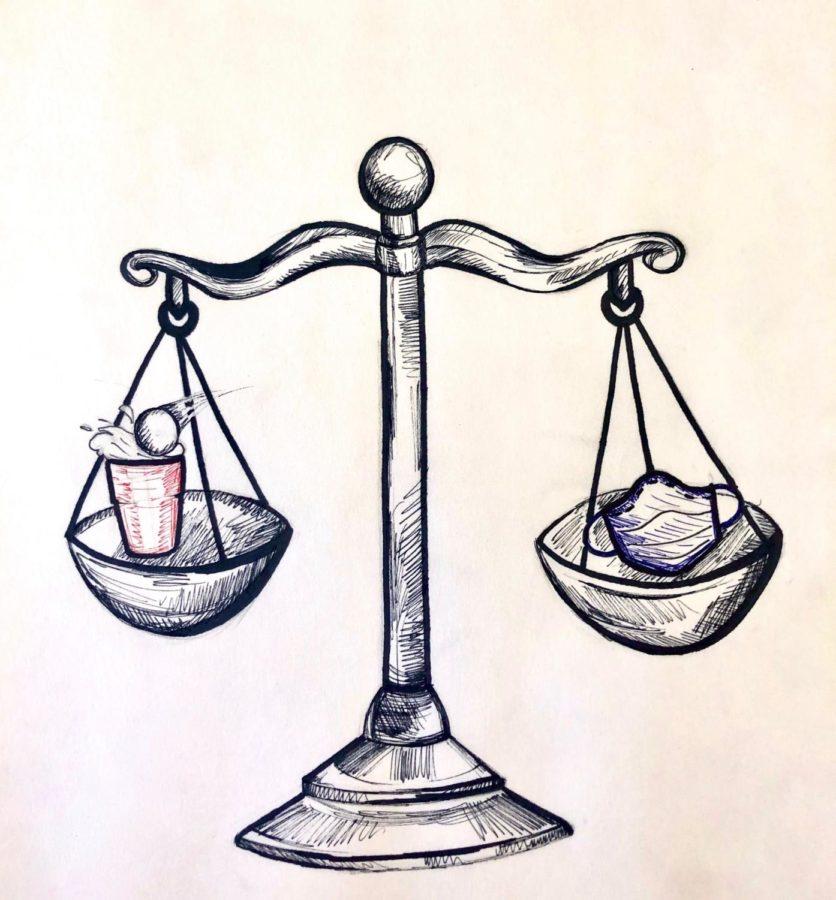

At least, that’s what one might assume from the University’s policy on Greek life. Administrators describe fraternities and sororities as “outside organizations” and “non-recognized group[s].” Oversight and accountability of Greek life has always been controversial at UChicago, and many people on campus—affiliated and non-affiliated—are tired of talking about it. The same debates about recognition have raged on UChicago Secrets every quarter I’ve been here, and it often seems that nobody changes their mind. But as students prepare to return to Hyde Park for fall quarter, we need to have this conversation again. The stakes have changed, and the University taking accountability for what happens at fraternities may now be a matter of life and death—not just for UChicago students, but for faculty, staff, and Hyde Park community members. Recognizing Greek organizations at UChicago during the coronavirus pandemic is a vital emergency measure.

The key terms “fraternity party” and “coronavirus outbreak” now regularly appear side by side in articles about universities reopening this fall. At the University of Southern California, at least 40 people tested positive for COVID-19 on the school’s frat row. At the University of Mississippi in Oxford, more than 160 cases were traced back to off-campus fraternity rush parties. At the University of Washington in Seattle, 155 fraternity members have tested positive in a summer outbreak—and school hasn’t even started yet. If such fraternity-driven spread were to occur at UChicago, can we be sure that administrators wouldn’t shrug their shoulders and ask, “What fraternities?”

Because of course, there are fraternities and sororities in Hyde Park. They recruit incoming UChicago students each autumn, throw weekly parties, and often get in trouble. The University’s failure to recognize frats and the risk they hold, and to be transparent about this calculus, is a major hole in its risk assessment for the fall. During an unprecedented crisis in which large indoor gatherings can quickly evolve into super-spreader events, fraternity parties pose a unique threat relative to smaller gatherings between members of a limited social circle. Events like Bar Night bring together people from every year, social group, and dorm in one sweaty basement. In normal times, that can be a wonderful thing, but this fall it means that isolated coronavirus cases could spread to every corner of the campus community after just one party. What’s more, it’s hard to imagine a “coronavirus-safe” version of Bar Night; you can’t drink beer, hook up with a new partner, or make small talk over blaring music while wearing a mask. Despite these dangers, reports from students on social media suggest that fraternities are hosting parties even now, as University students return to Hyde Park for the summer months. Implementing institutional oversight over Greek life this fall would demand that the University incorporate into its coronavirus planning the risks posed by Greek events and gatherings.

The concern with fraternities and sororities is not just that infections at parties will spread far beyond Greek organizations—members of these groups are themselves the individuals most at risk from an unregulated Greek scene this fall. Obviously, mixers and fraternity parties disproportionately include members of the Greek scene and thus carry a disproportionate infection threat for those groups. But even without parties, fraternity and sorority members who committed to living in houses with their brothers or sisters this fall are particularly vulnerable, because such group housing will not have the institutional support of on-campus dorms or the limited occupancy of the two-, three-, or four-person apartments occupied by most off-campus students.

Because of the particular risks borne by participants in Greek life during a pandemic, a temporary recognition measure would directly benefit members of fraternities and sororities during the autumn quarter. It would also allow Greek organizations to coordinate more easily with administrators and contact tracers to track virus cases that do arise. If someone in a fraternity did get sick, precoordinated collaboration between Greek leaders and contact tracers would allow for effective case tracking even if the school opts not to pursue further off-campus contact tracing. That’s not the only benefit to Greek students themselves. With a measure of recognition, the University could help find housing options for students who committed to living with their fraternity brothers or sorority sisters before the pandemic made such living circumstances particularly dangerous.

Members of Greek life have the potential to become campus villains this fall. If fraternities and sororities were to be the source of a major outbreak on campus, the organizations themselves would suffer—in part, of course, due to the harm endured by their members from the virus, but also if the connection was revealed by contact tracing or campus gossip. Were this to occur, the students responsible for the ground-zero gathering would likely face public condemnation—that, at least, has been the case elsewhere. Through conscious, public partnership with the University, Greek organizations ensure that they will not be scapegoated for institutional failures to protect students. Even more than that, they would have the chance to be heroes—not villains—of our plague quarter. Greek students could consult with administrators, RSOs, and student leaders to coordinate events to welcome both incoming and returning students. One thing that Greek organizations excel at is having fun and creating fun for the rest of campus. It may no longer be safe to host a weekly Bar Night, but fraternities and sororities will have unique insight into making this quarter at UChicago a joyful one despite our circumstances. Ultimately, such efforts will be essential to maintaining a sense of community and social connection during what will likely be an exceptionally difficult quarter for student mental health.

Of course, the way in which this recognition is carried out matters. With an emergency measure of fraternity and sorority recognition, members of Greek organizations will be able to partner with the University to plan for epidemiologically safe Greek life at UChicago this term. It is essential that recognition be done in partnership with the Greek organizations involved and that they contribute to the regulatory plans formed by the University. For instance, under no circumstances should armed UCPD officers be sent to shut down a social gathering held by UChicago students out of coronavirus concerns.

In 2016, this paper published a quote by Dean John Boyer: “I’m not an enemy of the Greeks. I’m not any enemy of any student organizations. My view has always been that of Hutchins: As long as people don’t violate the criminal laws of the state of Illinois, I don’t care what they do. It’s a free country and a free university.” Whether or not we should take Boyer at his word here is unclear. After all, underage drinking is a misdemeanor in Illinois, and sexual assault is a felony. Although both have occurred at UChicago fraternities in the past, neither has served as an impetus for administrative recognition of Greek Life. But Boyer’s words take on new significance during the pandemic. It may not have jail time attached, but the state’s stay-at-home order last May was a legal mandate. If such an order were to return, can students expect that Greek organizations will be accountable to that mandate? Without recognition, we can’t be sure.

Ruby Rorty is a third-year in the College and editor of Viewpoints.