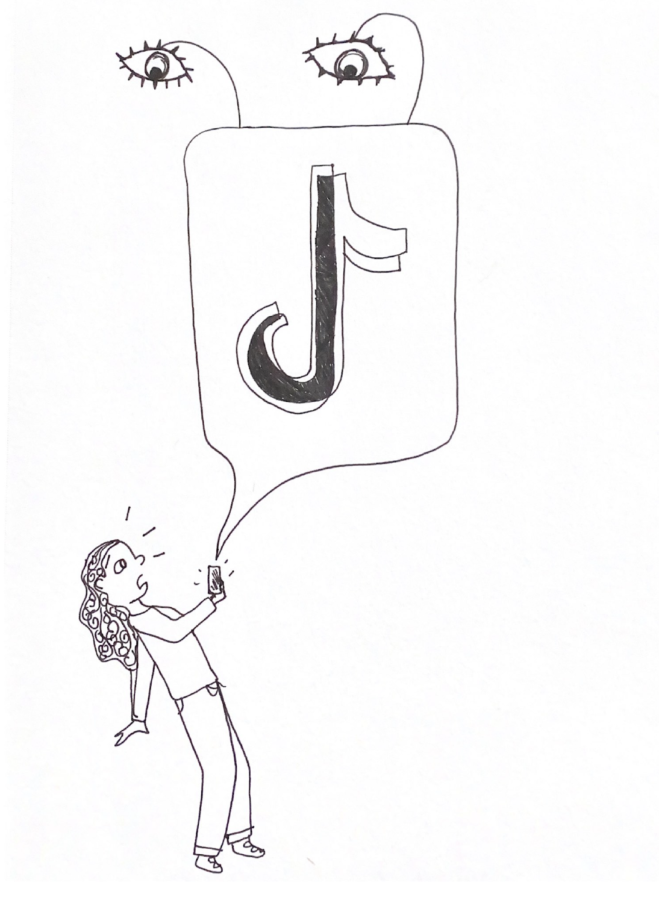

I finally caved last spring. After months of nagging from friends, COVID-19-induced boredom, and irritation at not understanding that dizzyingly complicated hand dance everyone seemed to know how to do, I downloaded TikTok. Now guides on how to cook dandelions, Dr. Doofenshmirtz cosplays, and ukulele tutorials—I don’t own a ukulele—eat up hours upon hours of my life, and I wouldn’t have it any other way. This may sound like Stockholm syndrome to the uninitiated, but the algorithm that governs one’s For You Page (FYP)—a bottomless stream of video content that identifies and adjusts to the user’s preferences over time—is well-known for its unsettling accuracy. It’s just uncanny enough to make you think, “what in the Black Mirror is going on?”

TikTok’s strength lies in the unique level of connectedness it fosters, making millions of people privy to inside jokes and building community around shared interests. Just ask UChicago’s very own @annumreport, @azulathecheezit, and @thekatamusic (love your stuff guys!). And yet, TikTok and similarly tailored media also divide, creating deeply homogeneous “bubbles” for users to inhabit. My FYP has little in common with even those of my closest friends. Instead, each of our pages supplies us with personalized jokes, music, and news carefully curated to our unique tastes, a far cry from the take-it-or-leave-it attitude of the newspapers and cable networks that comprised the bulk of American media a few decades ago. This utter personalization was once unique to TikTok, but Snapchat, Instagram, and YouTube have since stumbled into the ring, tailoring feeds and recommendations to individual users. Endless queues of highly individualized content is a reality that is here to stay—and with it, the implications it carries for our own campus community as we gradually emerge from a tech-dependent quarantine. For all its benefits, algorithmically tailored social media can undermine the value of the interpersonal and intellectual engagement UChicago prizes.

I’d wager that much of the student body finds genuine community in social media curated to identity and interests, particularly during the physical isolation that has characterized the last year and a half. I know my own understanding of the outside world, from the significant (accounts of the 2020 Black Lives Matter protests and mask distribution efforts) to the trivial (how to break a sweat whipping up dalgona coffee and attempt that inexplicable white freckle trend) was largely shaped by the information that made its way through the higher powers that preside over my FYP. It’s been an excellent way of finding faces that look like mine, voices that have me nodding along, and humor that seldom fails to make me laugh—all at my fingertips.

All the more jarring, then, is the transition into the bustling world of college life. Stepping back—or newly, in the case of both first- and second-years—onto campus has been enthusiastic, with everyone relishing the return to normalcy and the administration meeting us halfway with an inordinately long orientation for the Class of 2025. As a bright-eyed first-year, I’m thrilled to be soaking up everything college has to offer, particularly the amazing people and ideas I’ve encountered through my house, classes, and clubs. And yet, sometimes when I’m half checked-in to some conversation about the injustice of professor So-and-So’s heartless midterm curve, there’s a tiny corner of my brain whining for a more effortless diversion. Media that caters perfectly to my tastes dulls my interactions with others, sharpening my ears to when they twang out of tune and leaching the people around me of their hues. I might be less eager to entertain an interest I don’t share, and even less receptive to an opinion that seems to counter what I know.

At the risk of treading a well-worn path, it’s worth noting that highly individualized news is an obstacle to our community’s tradition of intellectual engagement. University President Paul Alivisatos recently reaffirmed the Chicago Principles at his recent inauguration celebration, describing the University’s longstanding commitment to the diversity of perspectives and backgrounds that draws students outside of their intellectual comfort zones. Filtered content is, in many ways, antithetical to this commitment. We see this in those who get their news from sources like TikTok—where information is boiled down into easily-digestible 60-second sound bites tailored to our convictions—or even those who exclusively seek out a specific publication, where the source’s political leaning acts as a filter.

Confirmation bias is already well documented in our tendency to actively select news sources that affirm our beliefs rather than challenge them, at the risk of blocking out a more complete picture of the issue at hand. If this principle already governs our choices, you can imagine how much the effect is magnified when we allow our brains to marinate in content that is specifically curated to block out anything that might displease us. This isn’t a Luddite’s exasperated conjecturing: a study run by the Wall Street Journal found that bots programmed with a general interest in politics eventually garner feeds populated with election conspiracy and QAnon content, among other radical views on both sides of the political spectrum.

Attention-grabbing favors uncompromising extremes, setting up and reinforcing increasingly myopic worldviews. An algorithm designed to optimize engagement has no stake in our media literacy after all and finds itself in opposition to the Chicago Principles’ commitment to putting perspectives in conversation and seeking out challenging ideas, rather than passively filtering our picture of the world.

Likewise, an algorithm that routes one exclusively into identity-based communities and interests due to factors like age, location, gender, or ethnicity can conflict with the University’s approach to engagement. “Echo-chamber” is a pejorative traditionally reserved for ideological communities, but I’d argue that it applies to culture as well. For instance, there’s a reason UChicago—almost uniquely among its peers—deliberately disallows specifying a roommate choice beyond the essentials. The school wants us to learn how to engage with people we wouldn’t otherwise choose to. TikTok drops content into your lap based on its knowledge of your identity, leaving a feed populated with people who look like you, listen to music you like, and so forth.

The experience of college inverts this. You’ve got a roommate from Taiwan with these awesome posters you don’t recognize, but would love to ask about. You complimented the girl a few doors down on her voice, and she’s happy to translate the Hindi tune for you over lunch. A tall kid in your Sosc mentions that he’s training for a 5k, and you’ve never considered why anyone would run for fun before, but maybe it’s time to lace up those sneakers.

Algorithms will assess demographics before spitting out a stream of spot-on content, but there may be unprecedented joy in engaging with media and hobbies that don’t naturally fall into our paths. There is value in being able to bridge divides of dissimilar identities, beliefs, and backgrounds, and that skill can’t be learned without settling into spaces we’re not initially primed to enter.

Pardon the grandiosity; of course, an app isn’t going to turn us into mindless zombies or render us incapable of human interaction, but we should recognize that this new form of highly personalized engagement with content alters the way we interact with our community. We ought to make up the difference by stepping outside the filter and consciously entering new spaces.

For instance, the University recently announced it’s providing of free access to the online editions of The Wall Street Journal, The New York Times, and The Washington Post for all students, faculty, and staff. Bearing in mind the center-right, center-left, and left-leaning skews of these sources, respectively, it’s a free opportunity to look into publications to which we wouldn’t initially gravitate—and as a bonus, the apps are pretty classy.

Likewise, my challenge for myself has been entering new spaces in the realm of media, like finding criminally under-budgeted indie movies to give a new filmmaker some love, trying my hand at ringing church bells (a severely underrated RSO), and mixing some of my uncle’s favorite jazz tracks into my egregiously basic Spotify playlists. Granted, these steps might look different for those with more exciting places to be on Friday nights, but the potential for variety and customizability is baked into the question “What can I do to step into a new space?” In answering it, we can round out this fall term, our return to UChicago normalcy, by self-curating our experience of the community.

Cherie Fernandes is a first-year in the College.