What does it mean to be Asian American at UChicago? More often than not, it means that you haven’t spent much time thinking about this question.

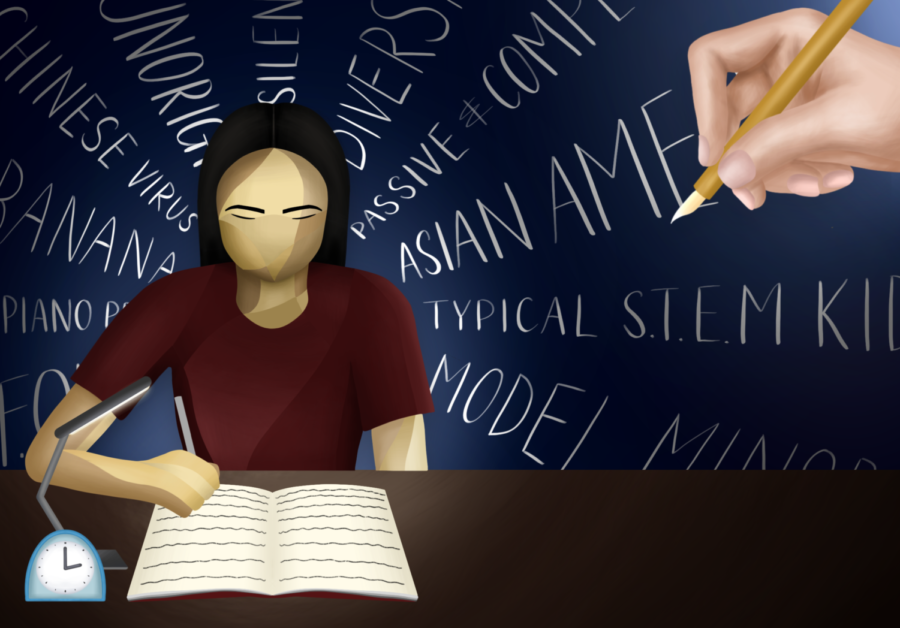

Being Asian in America often means straddling cultural boundaries, measuring yourself against the model minority standard, and having generalizations of your character be written and rewritten through narratives perpetuated by Ivy League discrimination lawsuits or headlines about high standardized test scores. It means either being tethered to or distancing yourself from stereotypes like the STEM whiz kid or the instrument-playing prodigy; it means either being complicit in silence toward racial discrimination or fighting to overturn the clichés of passivity and complacency that loom over you. There is no singular, correct answer to this question: Being Asian American at UChicago is as complex as the elusive Asian identity in America.

However, it’s become increasingly apparent that the Asian-American experience extends beyond just a demographic metric. Hate crimes against Asian Americans, specifically East Asians, have increased significantly since the beginning of the pandemic. Xenophobic sentiments have been amplified by former President Trump’s references to COVID-19 as “the China virus,” and the surge in attacks has shaken the Asian-American community; the shooting of six Asian women in massage parlors throughout Atlanta in mid-March have sparked national outcries against anti-Asian hate. This recent wave of violence is indicative of a larger problem: Despite having an extensive history of discrimination and resistance, we Asian Americans still do not feel like there is a space carved out for us. We are suspended between feeling welcome (thanks to carefully crafted performative efforts at diversity!) and the profoundly isolating sense of being othered. The message is clear: You are merely a transplant, a dangling appendage of a larger American project. Now, Asian Americans are emerging in America’s complicated political landscape after years of erasure and silence.

But have discussions surrounding this gone beyond social media activism? The high-stress academic nature of our school enables a culture where contemplating identity is secondary; we anchor ourselves in academic achievements while disregarding their dangerous effects on how we perceive our value. In my own social circles, the topic of being Asian American at UChicago rarely came up—instead, my conversations were often centered around academics, work, or college culture. Growing up, I had the luxury of not worrying about my racial identity. It merely lingered on the periphery; I was so swept up by the narratives fed to me that I internalized the idea that Asian-American history was meant to stay in the margins. It took a handful of headlines and eye-catching infographics to make me realize how little I knew about this history and how UChicago must do more to make its Asian-American students feel educated about their identities.

While there are spaces for Asian Americans at our school—namely, a handful of student-led registered student organizations (RSOs)—there isn’t the sense of an Asian-American community at UChicago. This is because we hail from a broad range of backgrounds and grow up with diverse values and experiences; the “community” is not monolithic in itself. This absence of a community lies in the lack of resources and courses to learn about this critical part of our backgrounds if we choose to do so.

The University’s curriculum is designed to encourage students to abandon conventional ways of thinking. We plunge ourselves into an entirely new intellectual environment at a faster pace, debate texts across a variety of disciplines, and build a deeper appreciation for understanding complex concepts. However, there are few opportunities at UChicago to learn about the broad range of experiences and identities for ethnic groups—an issue upon which Julia Spande expands in her recent column. Other peer institutions, such as Northwestern University, have entire programs dedicated to Asian-American studies. Of the spare courses on Asian studies currently offered by the critical race and ethnic studies major at UChicago, only two specifically focus on the Asian-American perspective, which is simply not enough. There need to be more opportunities to learn about topics such as Asian and Black relations in the U.S., Asian-American literature, the mixed-race experience, and deconstructing the normalization of “Asian” being associated with East Asians. Having this context will allow us to find a sense of equilibrium—to gain a broader perspective that escapes victimhood narratives without neglecting our colorful and nuanced history. Now, more than ever, we cannot resign ourselves to reductive notions of identity.

UChicago teaches us how to command a room, how to network, and how to challenge our mindsets, but it fails to live up to the “diversity” touted by its brochures. Creating a diverse and inclusive environment at our institution isn’t just a social initiative but an educational one as well. We must expand the number of opportunities to learn about Asian-American history; UChicago cannot just rely on a core curriculum centered on outdated perspectives of white men as a baseline for structuring its students’ viewpoints.

It is important not only to institutionalize the memory of our historical movements but also to learn how our identities have evolved and become tangled in the American social fabric. The education we seek should not be reminiscent of the abbreviated histories in our textbooks, ones that treat the experiences of people of color as an afterthought—we can only find our footing if others become more cognizant of the lack of spaces for us to learn and grow; UChicago must do the same.

Rachel Ong is a first-year in the College.