At the center of Maryland’s historic capital, Annapolis, lies St. John’s College. Described by The New York Times as “the most contrarian college in America,” St. John’s has attracted attention for its moves against the grain of the higher education scene of today. Notably, St. John’s has used donor dollars to lower tuition costs and for a long time held out against reporting data to the controversial—and increasingly influential—college rankings by U.S. News and World Report. As both the price of the education and the size of the endowment at the University of Chicago soar, and as its admissions rates decline, it may come as a surprise that, following a reorganization in 1937, St. John’s was once called “the college where the ideals of this University [UChicago] come closest to being realized in actual practice” by The Maroon (then The Daily Maroon). In fact, the general education curriculum at St. John’s has its roots firmly planted in the Great Books movement cultivated at UChicago in the 1930s, and the ethos of its curriculum, unlike at UChicago, remains largely unchanged to this day.

The New Plan

According to John Boyer’s A Twentieth-Century Cosmos: The New Plan and the Origins of General Education at Chicago, the beginnings of UChicago’s history of general education can be traced back to the New Plan of the 1930s. Often misattributed to former University president Robert Maynard Hutchins, it was Dean of the College Chauncey Boucher who, frustrated with the University’s heavy bent towards graduate education, formulated the University’s first core curriculum in the late 1920s.

Boucher sought to revolutionize undergraduate education through the creation of a cohesive general education curriculum that would take advantage of the University’s impressive roster of research faculty. He created four different year-long, interdisciplinary, and interdepartmental survey courses in the natural sciences, the biological sciences, the humanities, and the social sciences. Constructed in a lecture-discussion format, these courses relied on the collaboration of a number of the University’s senior faculty and, particularly in the sciences, intended to demonstrate to students the interdependence of disciplines across various fields of study.

The New Plan was constructed—both in its structure and in its content—to emphasize students’ individuality. Notably, the social science course made use of an array of primary sources and sought to place the burden of deriving social principles on the students themselves. On a structural level, the New Plan maintained its focus on individuality through its means of assessment. Attendance at lectures was optional, and instructors had no control over students’ grades. Instead, students were encouraged to work through the curriculum at their own pace. When the material was mastered, students were given grades through five different six-hour general education competency exams overseen by an independent Office of the Examiner.

President Hutchins and The Great Books

Hutchins, though initially an ally of Boucher when he was appointed president in 1929, eventually became one of the greatest challengers of the New Plan. Hutchins’s push against the New Plan started in 1930 after he became acquainted with Mortimer Adler, an instructor at Columbia University who would go on to become one of the leaders of the Great Books movement.

According to a 2009 dissertation by William Scott Rule, Seventy Years of Changing Great Books at St. John’s College, which details the history of Great Books at St. John’s and beyond, Adler himself first encountered the idea of a Great Books education at Columbia University as a student in John Erskine’s General Honors course, a course which Adler would eventually go on to help teach. The seminar-discussion course would go on to form the mold for Columbia’s core curriculum and lay the foundation for how a Great Books education might be implemented. Erskine saw the defining characteristic of a great book to be its timelessness.

“The Great Books are those which are capable of reinterpretations, which surprise us by remaining true even when our point of view changes,” Erskine wrote in his 1928 book, The Delight of Great Books. “If a book no longer reflects our life, it will cease to be generally read, no matter what its importance for antiquarian purposes.”

Hutchins had taken a liking to Adler when the two met several years before. So when Hutchins became president in 1929, he used his position of power to entice the aspiring philosopher to Chicago three years later with a philosophy professorship, a position Adler had failed to land at Columbia. Having admitted, according to Rule, to not giving much thought about what education should be prior to accepting the presidency, Hutchins was quickly converted by Adler into a staunch proponent of the Great Books. Soon enough, Hutchins resolved to replace the New Plan with a Great Books curriculum.

Hutchins constructed a curriculum committee and tasked Adler with formulating four lists of great books to replace the curricula in the four existing divisions of the New Plan. However, the lists were met with intense opposition from the faculty on the committee, and Hutchins’s first attempt at a Great Books curriculum ultimately failed.

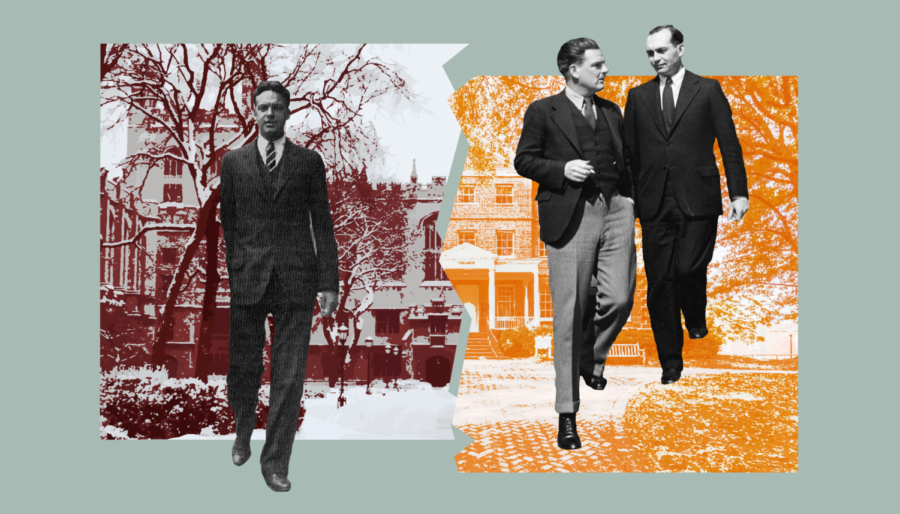

Hutchins didn’t give up on his vision, however. In 1936, he brought in several influential outside figures, including Scott Buchanan and Stringfellow Barr of the University of Virginia, and he gained a powerful ally in Dean of the Humanities Division Richard McKeon. Still, the proposal managed to inflame faculty.

“The faculty really had a great deal of anxiety about what Hutchins and Adler were trying to do in the late 1930s. Part of it was personality-driven. A lot of faculty just didn’t like Hutchins, thought he was very autocratic and telling them what to do. And it's a long tradition around here. The faculty have the right to organize the curriculum the way they want,” Boyer, dean of the College and historian of the University, told The Maroon.

Ironically, though, it was disagreements within the committee of Great Books supporters that ultimately defeated Hutchins’s second attempt. The committee simply could not agree on what books to read or how to read them, and the idea of an all-encompassing Great Books education at Chicago was put aside.

A Vision Realized: Great Books at St. John’s College

Though the Committee on the Liberal Arts failed to produce a Great Books curriculum at UChicago, according to Rule’s thesis, it did not fail to produce a Great Books curriculum altogether. More than 700 miles away in Annapolis, Maryland, a struggling St. John’s College, lacking a president and official accreditation, had heard about the committee and contacted Hutchins hoping to receive his assistance. While the opportunity to implement a Great Books program at a smaller institution intrigued the committee, Hutchins himself was uninterested in leaving his position at a large, prestigious institution like UChicago to fill the role. Realizing this, Barr and Buchanan agreed to leave the committee for St. John’s and take on the roles of president and dean, respectively.

Both experienced academic administrators, Barr and Buchanan implemented a completely new curriculum and administrative structure at St. John’s.

“The New Program implemented in 1937 redefined the college in such a way that it, aside from the physical buildings, established a new institution,” Rule wrote.

The pair instituted a Great Books curriculum that was completely compulsory and spanned all four years of undergraduate education. Most of the existing faculty, who experienced difficulty with the curricular transition, chose to leave and were replaced by new faculty members. Instructors of this new curriculum adopted the singular title of “tutor”; the terms “professor” or “teacher” were avoided because pedagogical responsibilities were to be attributed exclusively to the authors of Great Books.

Joseph Macfarland (Ph.D. ’96), dean of academic affairs at St. John’s, described this environment, which has endured into the present, in an interview with The Maroon. “At St. John’s, there are no departments. There are no ranks among the faculty. We’re all just tutors. We don’t have postdocs. And it’s a very egalitarian culture in which everyone shares as part of a single community.”

The restructuring of St. John’s was a phenomenon of great interest to the University of Chicago community. In 1937, Hutchins was added to the Board of Visitors and Governors at St. John’s, and in 1939, Barr and Buchanan, alongside two members of St. John’s new faculty, drafted a four-part series in The Daily Maroon.

The introduction to the series reads: “The educational ideas being tried out at St. John’s are of obvious interest to the University community, both for their relation to education in general, and for their relation to education in particular, to Hutchins’s educational proposals. For this reason, several members of the college’s overworked staff have written articles explaining their school to The Daily Maroon readers.”

At the heart of this new curriculum was the seminar, where students were to discuss the Great Books under the supervision of two or more tutors. These seminars were discussions structured for intellectual play and rigorous argument and were meant to challenge students and tutors alike.

“Each seminar has at least two instructors to lead it, from different ‘fields.’ We wouldn’t trust one professor alone with such a group. He might start telling jokes, or indoctrinating, or bludgeoning young persons over the head with specialists’ terminology, or any one of a dozen of the things professors commonly do when they lead a student discussion without being chaperoned by a colleague,” Barr wrote in The Daily Maroon. “A good seminar is likely to make a monkey of somebody, either a student or an instructor, by pushing him into a position he can’t get out of without backing out. It is good for students to be made monkeys of, and instructors too.”

These seminars were then supplemented by lectures and, for the sciences and mathematics, tutorials and labs. Even the sciences, however, were to be taught via Great Books rather than textbooks. George Comenetz, one of the original tutors at St. John’s, described how this approach allows students to better understand the development of science and to critically examine authority in the field.

“A unique advantage of the great books is that they make great errors. Galileo deserves especial credit in this condition. The effect on a student’s attitude towards authority can only be a healthy one,” Comenetz wrote in The Daily Maroon. “There is at least a fair chance that a study of science in its development will be better for these students in training their minds and in showing them its place in knowledge as a whole, than the more efficient study of the sciences as they stand today.”

The College: Hutchins Gets His Revolution

As debate over the curricula heightened, two of Hutchins’s main opponents—Boucher and economist Harry Gideonse—left the University. Boucher resigned over frustrations with attacks on the New Plan, and Gideonse was ousted by Hutchins, who refused to grant him a tenured position despite the continued recommendation of the Department of Economics. With his main opponents out of the way, Hutchins had paved a clearer path for the kind of sweeping reform he sought to achieve in his role as president.

This trend culminated in Hutchins dismantling the College in 1942 under the New Plan, in which most of the faculty, like today, also maintained departmental positions. Instead, Hutchins recruited a new faculty—larger than three of the four divisions—appointed solely to the College and pushed dual-appointed faculty out of the College and into their respective departments. He tasked the new College faculty with the creation of a full-time, mandatory curriculum that would span four years instead of two, as in the New Plan. Instead of entering college at grade 13, this curriculum was to span grades 11 to 14 and would culminate in the awarding of a bachelor of arts degree., now controlled by the College instead of the individual departments. With departments out of the picture, this new program did away with majors altogether.

“The idea was to have early admission. The high schools are doing a terrible job,” Boyer said. “Let’s get the kids, smart students, take them out of the clutches of these mediocre high schools, bring them to a great university, and put them through a rigorous program of four years of general education training. Then they could go on to medical school…the whole idea of specialization should come when you want to get your master’s or Ph.D.”

Hutchins waged war on the faculty divisions, and he ultimately came out on top. Though he had abandoned the idea of a Great Books curriculum in its purest sense, as a board member of St. John’s who was closely following the success of the Great Books over in Annapolis, he certainly had the Great Books in mind as he fleshed out his reforms. His new curriculum, much like that of St. John’s, was structured around small seminar-style classes, and he enjoyed the fierce loyalty of the newly appointed faculty body in the College.

According to Boyer, this loyalty extended to the student body.

“As a younger person back in the 1980s, I would meet some of these alums and they were passionately, passionately in favor of this concept. I mean, they thought this was the world's best way of organizing knowledge. To use the kind of colloquial [phrase], they had drunk the Kool-Aid.”

While Hutchins was, by many accounts, an adept academic visionary, he did not share this same aptitude for fiscal management and fundraising. Hutchins’s fiscal ineptitude, coupled with the great cost of the large College faculty required for the small class sizes of the new curriculum, led to large budget deficits and stagnating endowment growth that ultimately forced Hutchins to leave his position in 1951.

“The board was holding him accountable for getting us into this very dire financial mess,” Boyer said. “After what was a long time for a president of a university, Hutchins decided to leave.”

A Post-Hutchins College and the Core of Today

Following Hutchins’s resignation, Lawrence Kimpton, a professor of philosophy, was appointed to replace Hutchins. Kimpton quickly rolled back many of Hutchins’s reforms: He reintroduced majors into the College, took away much of the College’s curricular autonomy by allowing departmental faculty to teach undergraduates, and restructured the college to include grades 13 to 16 rather than 11 to 14.

“Kimpton was a very shrewd guy,” Boyer said. “He had a Ph.D. in philosophy. He was kind of a humanities guy. But he took one look at this and he said, ‘Look, this is not sustainable. I can’t run a college with, you know, all these [departmental] faculty, many of whom actually want to teach.’”

The College faculty, he said, needed to make room for more specialized coursework.

“It was very painful for the College faculty who were hired to teach these three or four years of humanities. They’re told shrink it down to one year,” Boyer said. “Okay, how do you shrink a three-year [course] down to one year?”

Kimpton ushered in an era of curricular disarray that lacked the unified vision of the Hutchins plan, as responsibility for general education was fragmented among the departments. In 1964, the College was restructured into five collegiate divisions (biological sciences, humanities, physical sciences, social sciences, and new collegiate), and in 1966, a compromise that sought to restore curricular unity allowed each of these new divisions to create their own versions of their Core components, with less stringent requirements.

“Over time, faculty would begin to come forward and say, ‘Okay, I like general education or I like social sciences, but I don’t like Sosc 2. I want to have a different course.’ And so what the College began to do is to allow variants,” Boyer said. “That began in the ’60s and ’70s, really, as a way of responding to the desire for more diversity and more plurality of approaches among the faculty.”

The next attempt at significant curricular reform occurred in 1982, under the leadership of Dean of the College Donald Levine. Levine sought to address the curricular disarray that characterized the post-Hutchins era up until this point, recentralizing control over undergraduate education. Under Levine’s plan, which went into effect in 1985, Core classes were to occupy 21 of the 42 classes required for the baccalaureate degree. While many Core options remained, Levine did reestablish a common curricular platform for all students.

While more organized than the curricular chaos of the ’60s and ’70s, Levine’s curriculum faced several challenges. First, the large size of the curriculum forced many students to push their Core classes into the third and fourth years of their undergraduate studies, which went contrary to a previous conception of Core classes as initiatory prerequisite courses.

By their third and fourth years, students have “already been inducted into other educational cults…. They've already learned the throes of economic or of race theory,” said Harper-Schmidt Fellow and Self, Culture, and Society Core sequence instructor Sean Dowdy, an alum of the University’s M.A. Program in the Social Sciences who received his Ph.D. from the Department of Anthropology. “And so they’re coming in with those lenses and sort of saying, ‘Okay, we’re going to rip Durkheim apart, we’re going to rip Marx apart,’ without having that shared early experience together of initiation.”

Second, the decentralized curriculum caused the feeling of loyalty among College faculty, now largely co-appointed to a department, to decrease. While these courses were previously under the control of faculty appointed solely to the College, departmentally appointed faculty wanted no part in classes over which they had no intellectual control.

University president Hugo Sonnenschein’s administration, during Boyer’s tenure, ushered in a new wave of curricular reforms in the mid-to-late 1990s. A series of intense debates began about how to address difficulties surrounding Levine’s reforms.

“Looking back on it, [the curriculum negotiations] were fun. I would never want to do it again. But it was like negotiating a nuclear arms control treaty with all of these different interests,” Boyer said. “So you try to talk through it and six months later we arrive at, I think, a reasonable compromise.… That’s what Hutchins did not have a lot of patience for. I’m not saying that my approach is better than his, except that I got the curriculum through and it’s still here. And I didn't get kicked out like Hutchins.”

The agreement that was reached in 1997 and ultimately implemented in 1998 was a Core much the same as exists today. The overall course load shifted from 21 to 18 courses, occupying one-third of undergraduate study. The structure was similar to that of Boucher’s New Plan. Year-long sequences in the biological sciences, humanities, civilizational studies, and the physical sciences were replaced by two-quarter “doublets” with the intent of allowing a greater level of experimentation within the Core and the development of new Core options. Departments were not allowed to occupy this space with increased major requirements, granting students another third of their planned coursework to experiment with electives or to add another major.

While the Sonnenschein-era reforms did address many of the issues of the 1985 plan, it was, and still is, not without controversy. Many members of the University community, including Dowdy, continue to critique the reforms as an attempt to make a “Chicago lite” experience that is more marketable to the general public and thus more profitable.

“Questions of pedagogy and questions of the philosophy of education were subordinated to economic motives,” said Dowdy. “The Sonnenschein administration and the suits that he brought in wanted to rethink not just the College, but the University as a whole, its infrastructure, its bureaucracies, on the basis of how to be profitable, with the endowment being the real bottom line.… To me, that’s disingenuous.”

The Future of General Education

With more than 100 years of core curricula under its belt, the issue of what a general education should be and what it should look like remains a contentious issue at the University. General education at UChicago has been a tumultuous journey. However, UChicago remains among the select few institutions that, among a higher education scene that has been pushed more and more into specialization, has managed to maintain a firm commitment to general education as a worthwhile endeavor.

St. John’s College remains not a relic of what was at UChicago but an example of what could have been; while St. John’s maintains a rich educational tradition with roots grounded in UChicago’s educational philosophy, UChicago has never truly had a Great Books curriculum itself. St. John’s appears, then, as one of the few remaining torchbearers of an all-encompassing general education. While the list of the hundreds Great Books on offer at St. John’s has changed over the years (for example, Macfarland highlighted that W. E. B. DuBois now plays a more prominent role in the curriculum), Rule notes that a majority of the authors on the list—including Aristotle, Dante, Hegel, and Shakespeare—have remained since day one.

One of the main criticisms of the St. John’s Great Books curriculum, which Dowdy voiced, is that it is elitist and eurocentric, representing solely the Western tradition.

“The very term ‘Great Books’ is elitist. Yes, the very term ‘canon’ is elitist because what those words do, those signs, is they automatically make you think that there is going to be a drawing line between what counts as great [or] not great or what counts as canonical or not canonical,” Dowdy said. “That being said, I hold a slightly more nuanced view on this, in that I think there are some texts that are fundamental.… There’s this idea of cultural picturability. Freud has been read in Egypt, in India and China and far-flung parts of Siberia. That we should pretend as if Freud is just a white man is a problem. Freud opened up a possibility in thinking about human subjectivity that has been consumed the world over, that has not been colonially imposed but intentionally, deliberately read.”

Macfarland does not agree with this assessment of the Great Books. While he acknowledged that the Great Books are a Western tradition, he stressed that the curriculum’s scope is limited by its four-year window.

“At St. John's, I think there’s a very strong notion that it should be for anyone, for everyone to read the books which have played a foundational role in developing the culture and the thought which we’ve inherited,” he said. “The West doesn’t have a monopoly on great thought, but the authors that are in our tradition talk to one another.… So the further you go afield, the more likely you are to bring something in as a kind of token—which I think doesn’t do either the tradition or the word justice, or it doesn’t have the same lines of communication with the series of voices that you’re bringing together.” For a Great Books education that veers off the beaten path of the Western tradition, Macfarland points to the eastern classics M.A. program at St. John’s.

St. John’s, too, has had to adapt. While the structure of the curriculum remains largely the same, it occupies a much different role in an era where U.S. academia has begun to reject the West’s supposed monopoly on “great” thought. According to Macfarland, it’s clear that St. John’s no longer sees the Great Books curriculum as general in the truest sense, but rather as one kind of specialization or version of what a general education can be.

“I think we’ve lost a little bit of that evangelical spirit, the notion that somehow the good news of St. John’s ought to be spread, has to be spread everywhere,” Macfarland said.

This illuminates for Boyer one of the biggest problems in formulating a general education: It can never be truly general or all-encompassing. “I’ve always been a little bit skeptical about being too prescriptive about what general education is beyond that it be a general introduction to knowledge and [that] there be small groups, there be a lot of writing, and there be a lot of conversation in the classroom,” Boyer said.

As for Dowdy, in his Self, Culture, and Society sequence, authors as varied as the anarchist anthropologist David Graeber and the Arab philosopher and social scientist Ibn Khaldun have been added, alongside the likes of Adam Smith and Karl Marx.

“General education should always be experimental. It should never be done right,” said Dowdy. “There’s one thing that I think should not be debated, and that’s [that] a general education, in a true liberal arts sense of the term, is necessary.… It was necessary then in the creation of this university, and it’s necessary now. Not because it’s the University’s brand, but because it works. It generates people like Bernie Sanders. And I’m willing to put money on that.”