On February 25, 2021, the Smart Museum of Art launched a new web series called “Close Looking” with an accompanying conversation on the work of American artist, activist, and former UChicago student Erika Rothenberg. Rothenberg was kicked out of the College for participating in a student protest. Her series is meant to replicate in-depth discussions with museumgoers and museum staff that have been postponed due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

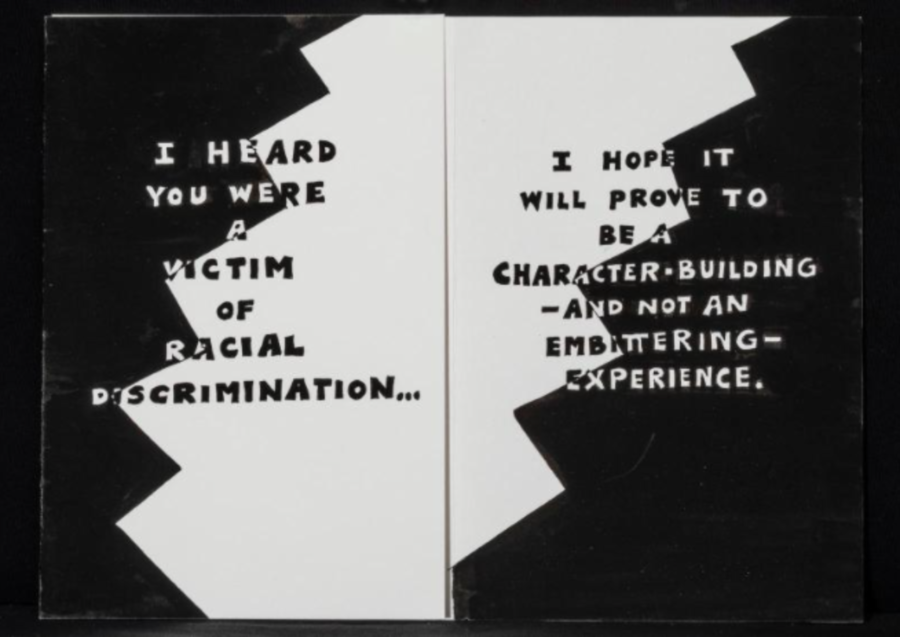

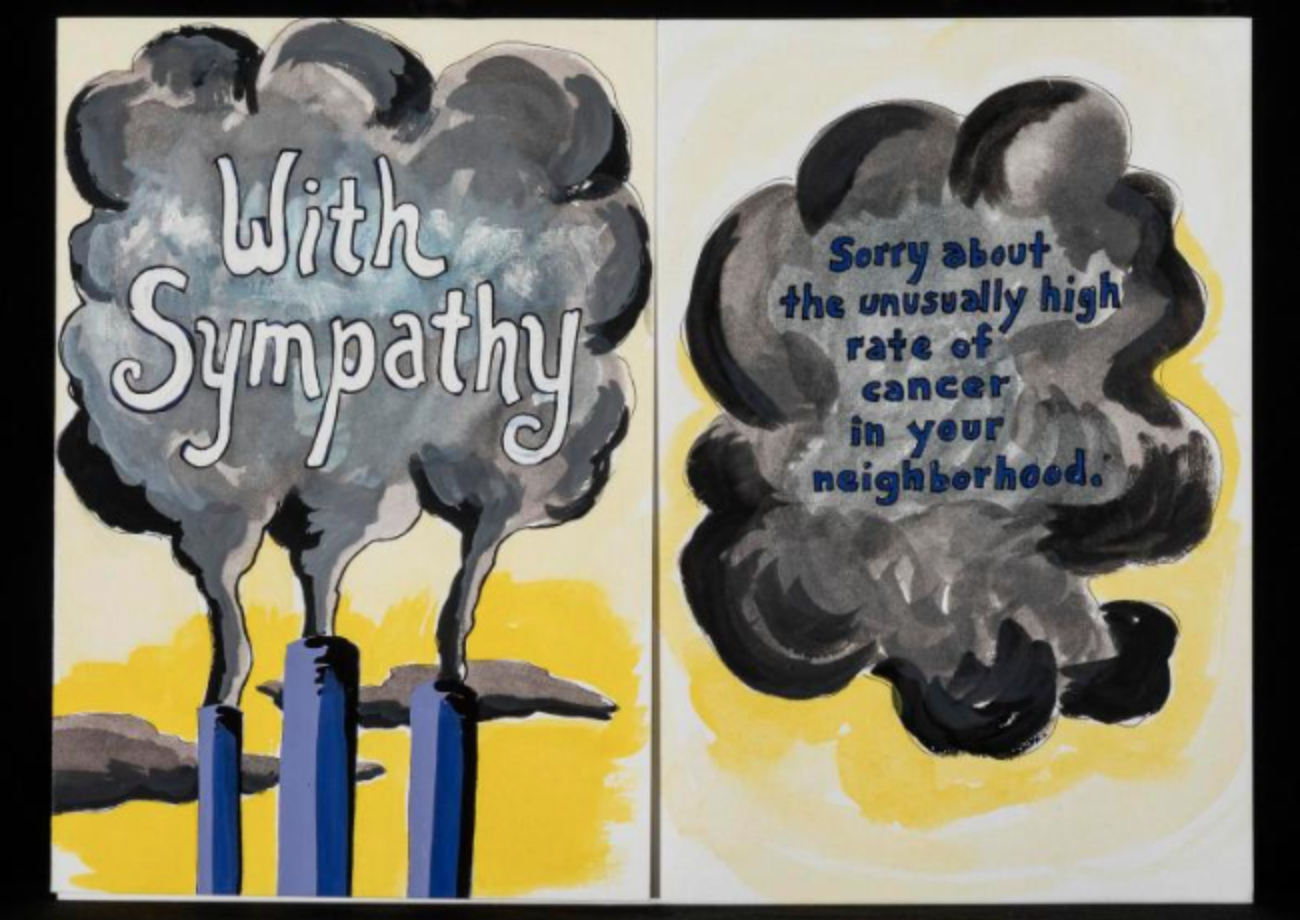

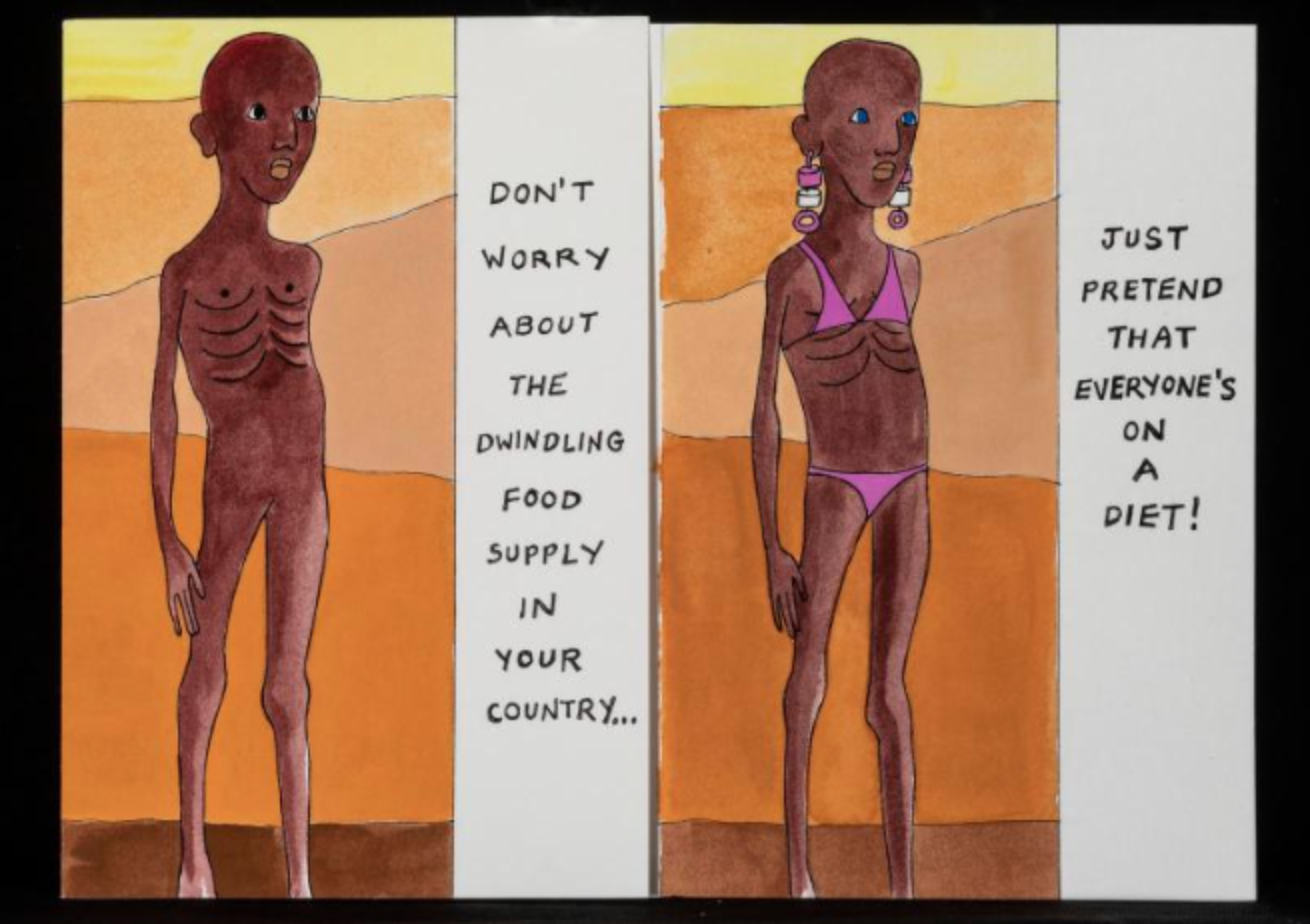

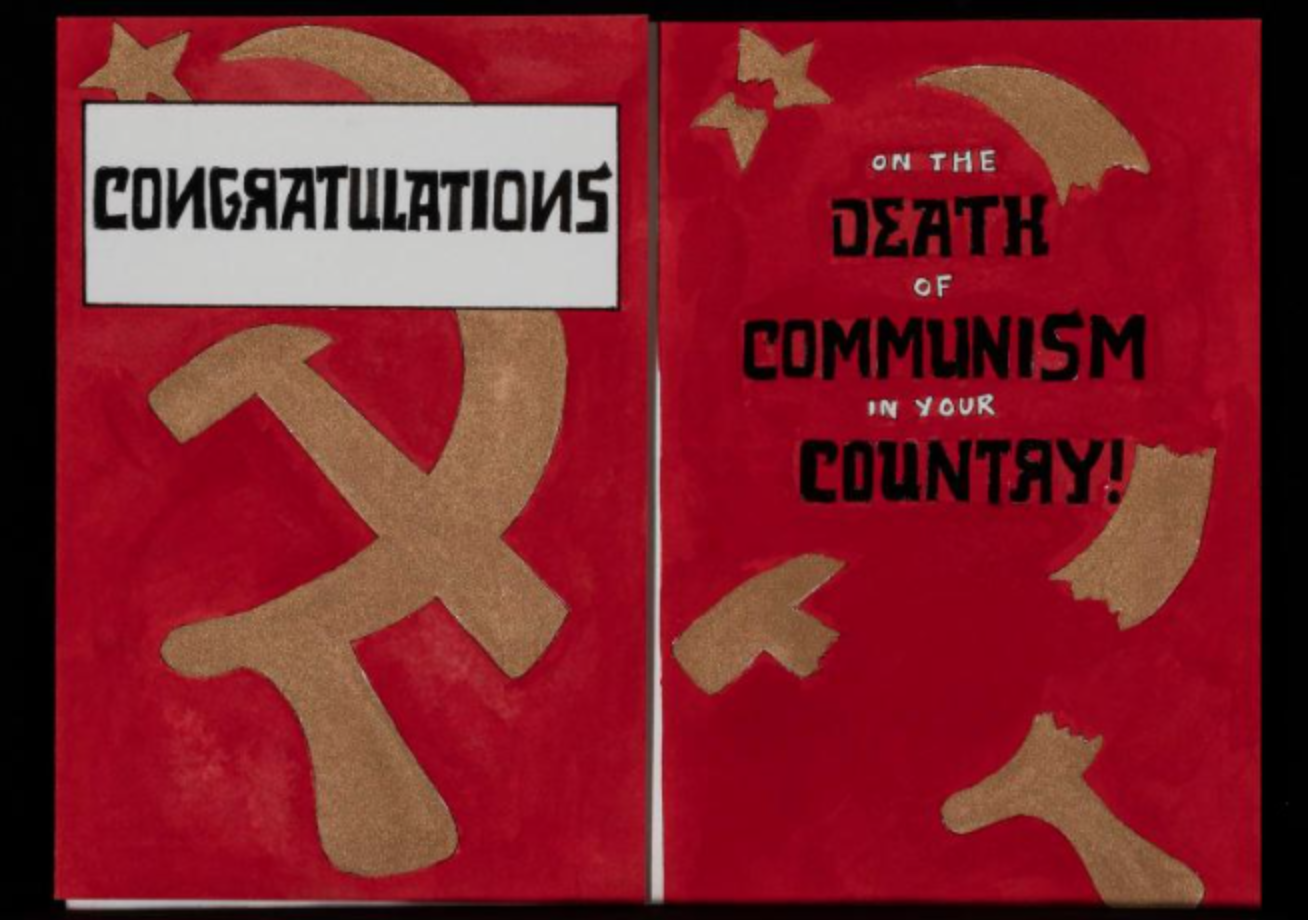

Hosted by the Smart Museum’s Academic Engagement Graduate Intern Gary Kafer, the event highlighted the museum’s collection of Rothenberg’s satirical greeting cards. These cards have been featured in the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA); they examine Rothenberg’s use of humor to express messages about taste, care, and politics. The collection of greeting cards is part of the museum’s larger exhibition Take Care, which features more than 50 works of art across media from Smart’s own collection. The exhibition seeks to unpack matters of care from the personal to the collective and aims to answer the question of how we care for ourselves and others.

The online conversation highlighted how Rothenberg explores this idea of care in her greeting cards, especially what it means to “care” about people who are suffering. Through the use of satirical and sarcastic language paired with ironic images, Rothenberg forces her audience to consider the lack of empathy in the American political landscape.

While her cards contain familiar greeting card language including “sorry,” “condolences,” and “with sympathy,” they are far from the average greeting card. Some apologize for “the unusually high rate of cancer in your neighborhood” and others for the fact that the “C.I.A. assassinated your president.” The cards satirically address political issues, such as the Cold War, the rise of consumerism, climate change, and racism by expressing false care for those who were burdened by these issues.

“Greeting cards as we use them are often used and often given and received as signs of care,” Kafer said. “But in Rothenberg’s hands, greeting cards are a medium of critique.”

For Rothenberg, that critique is primarily of American exceptionalism. “Rothenberg aims to expose the values and assumptions of American exceptionalism in didactic and humorous ways,” Kafer explained. He added that, when referring to American exceptionalism, he means the notion that America’s values, politics, and history uniquely destine the country to play a positive role on the world stage.

The conversation also focused on the relevance of Rothenberg’s work today. Are her critiques of racism, war, and anti-communism applicable 30 years later? Kafer thinks so. He said that the subjects of the cards are especially relevant in today’s climate, one plagued by inaction and a “thoughts and prayers” mentality.

“Sending a greeting card is a way of calling attention to an issue but also absolving oneself from having to take part in it because you’re kind of saying, ‘You have my sympathy and that’s about it,’” Kafer said. “It’s kind of equivalent to a lot of the conversation we have today when people say ‘thoughts and prayers’ after a natural disaster or mass shooting.”

Rothenberg’s work was, and still is, a call to action, a cry for the American public and government to actually “take care” of others beyond offering half-hearted condolences and false promises. Thirty years since she began creating them, her greeting cards continue to remind us that there is still a long way to go in terms of this care, both for our country and for other countries around the world.

For more programs and exhibitions from the Smart Museum, visit smartmuseum.uchicago.edu.