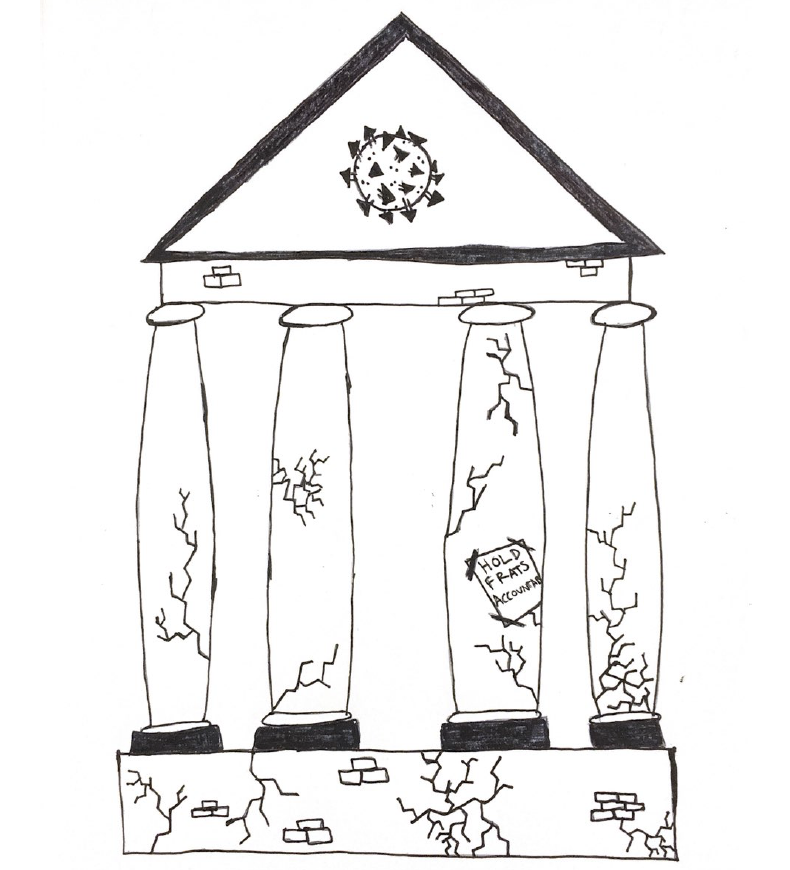

It is absolutely right to be furious right now, enraged and upset at how the careless actions of a selfish fraction of our university have stripped the whole of its freedoms. Because of “parties held by off-campus fraternities,” on-campus students must quarantine, confined to their rooms just as the breeze warms and spring flowers finally begin to bloom. And now, under the banner of a new tragedy, the student body has already begun to perform the exact same theater that has left us stuck in place and at the mercy of the exact same guilty parties: calling for the abolition of Greek life at the University of Chicago.

“Abolishing” Greek life is so popular because it seems like common sense to want to strike a problem right at its core; no more frats means no more fraternity parties and all the sexual assault, discrimination, and COVID superspreading that come with them. But true common sense points out the obvious obstacle of such a prescription: how, despite all those issues, the University still refuses to take the necessary first step towards abolition by recognizing fraternities and clearly does not take the prospect of any sort of abolition seriously. In pursuing unrealistic ends, advocates neglect what can be done in the present, with the potential to achieve, pragmatically, the same results. By utilizing a little-known University judiciary mechanism, advocates can rightfully pursue party hosts, fraternity or otherwise, under the University’s own policies on disruptive conduct.

Abolition is often the beginning and the end of the discussion of what must be done about Greek Life at the University of Chicago. This is, in part, because cooperation with fraternities has (rightfully) long been seen as a failure. In 2017, The Maroon Editorial Board called “Fraternities Committed to Safety,” a pledge organized by the Phoenix Survivors Alliance to keep fraternities in line, “a hollow solution,” bound to become “a toothless publicity exercise.” Two years later, the Phoenix Survivors Alliance themselves admitted, in a student government endorsement, that they had given up on working with frats. Though the PSA focuses on sexual violence, the message they delivered was clear: simply put, following the advice of the PSA, looking for a solution that cooperates with fraternities would not be an “effective use of our time.”

The other reason for the support of Greek abolition—and solely abolition—comes from a UChicago obsession with radical performatism, the manifestation of which I have written about as it appears on both the Right and the Left. People pay lip service to the idea of abolition because it requires no real commitment or effort. After all, when it comes to abolishing Greek life, it’s not the students who have to do anything, but the administration. If no action is taken, then the student can simply absolve themselves of any sort of agency by resting all of the responsibility at the feet of the administration. They can go to Bar Night with a clear conscience, convinced that they did all they could to fight against fraternities. Caught up in the theater of the word, “abolition,” the Greek “abolitionist” forgets that a radical word is meaningless unless cached in radical action.

Proposing sit-ins—where non-Greek community members occupy Greek houses—is an unwitting continuation of this radical performativity, in that the radical nature of the activity blinds the supporter to UChicago’s unique Greek context. The only time a sit-in was “successful” in removing Greek life happened at Swarthmore College, solely because the administration had already been taking steps to curtail it. A year prior, Swarthmore convened a committee that recommended that the school no longer lease on-campus houses to Greek organizations, a policy that would have effectively killed fraternities on its own. It was able to make this recommendation for two reasons. Firstly, and most importantly, the school both recognized and played an active role in fostering fraternity activity by directly leasing houses to the groups. Secondly, Greek life at Swarthmore was already on its last legs. Most coverage of the sit-in neglects to mention that, in the moments before the administration made the “bold” move to ban Greek life, the school only had two fraternities. Sit-ins didn’t kill Greek life at Swarthmore; the withering effects of time on Greek membership and an administration already set on limiting Greek life did. Suggesting sit-ins, then, isn’t radical as much as it is neglectful of UChicago’s Greek context, which is almost a direct opposite.

The fatalism that comes with failed cooperation and radical performativity combine to create a situation in which the student body is needlessly dependent on the administration. It has half as much motivation to generate a successful solution. What’s the use in trying to solve a problem that the troublemakers seem to have no motivation in fixing? What can be done if it is thought that having the administration’s support through recognition is the only way forward? The Disciplinary System for Disruptive Conduct, it would appear, is the answer to both of those questions. There is no need to work with the troublemakers if, through a disciplinary system, they can actually be punished for causing superspreader events. There is also no need for the University to take the step that it likely never will if our path of regulating Greek life is already built into its infrastructure.

The Disciplinary System for Disruptive Conduct is relatively new, introduced in 2017 in light of the University’s then-burgeoning principles of free expression. When, as was reported by The Maroon, the system was initially debated by students and faculty, concerns were raised that it would jeopardize the expression of marginalized protestors. Now, however, it is clear that the Disciplinary System for Disruptive Conduct can actually help students in obtaining righteous recourse that had not been thought of as possible.

According to the system’s page in the Student Manual, it is designed to punish instances of unprotected “expressive conduct” by a member of the University community, which, importantly and relevantly, includes types of expression that lead to the “disruption of ordinary University activities.” Also included are provisions against expression that “substantially obstructs, impairs, or interferes with…the rights and privileges of other members of the University community.” It’s also not difficult to make a complaint. So long as the evidence is compiled and specific names and actions are provided, “anyone” can submit a complaint to the associate dean of students in the University for disciplinary affairs.

I’m no lawyer, but it seems to me that a gathering organized by certain members of the University community would certainly count as a form of expression. As it happens, that expression, by shutting down in-person classes and forcing students into lockdown would most definitely fall under the disruption of ordinary University activities. All that’s needed then, to complete a complaint under the Disciplinary System for Disruptive Conduct, would be names and descriptions of activity, such as taking on a leadership role in organizing the event.

Though the Disciplinary System for Disruptive Conduct most relates to the fraternity COVID superspreader, through its protection of “the rights and privileges of other members of the University community,” its effect, if properly utilized, could be expansive. An example of protected rights and privileges, for example, includes protection against the “use or threatened use of force against any member of the University community or his or her family that substantially and directly bears upon the member's functions within the University.”

Not every complaint will be successful, of course, but the knowledge that University members have a way of securing justice might be enough to scare organizers into putting more effort into ensuring the safety of the community. Effort must also be taken on behalf of the community, though. Infractions can be reported to COVID trackers and through the disruptive conduct system, but people have to be present to witness the infractions in the first place. It would be a large commitment, but, when the campus returns to normalcy in the fall and parties come with it, perhaps it would be best for a dedicated group of third-party observers to keep a watchful eye.

Greek organizations, through their dues, infrastructure, and institutionalized secrecy, are inherently better equipped to foster the conditions that cause broad problems for the University community. By not losing sight of what can be done in the now, however, the community might be able to, for a change, actually fight back. Proving that actions have consequences go a long way for those with an unearned sense of invincibility.

Matthew Pinna is a fourth-year in the College.