An open-source software program "Fawkes," developed by a UChicago research group, can modify images in ways largely imperceptible to the human eye while still rendering faces in the image undetectable to facial recognition systems.

Facial recognition software is often trained by matching names to faces in images scraped from websites and social media. The aim is to develop software that can correctly identify pictures of people’s faces it has not previously encountered. This allows people to be easily identifiable when an image of their face is captured in public spaces, such as at a political protest.

By changing some of your features to resemble another person’s, the Fawkes “mask” prevents facial recognition software from training their model. A facial recognition model is successfully trained when it associates your name with a distinct set of features and can accurately recognize you in future pictures. The Fawkes mask decreases the difference between your set of facial features and other people’s, thus preventing facial recognition software from training. The Fawkes mask is largely imperceptible to the human eye but deceiving to machine learning models.

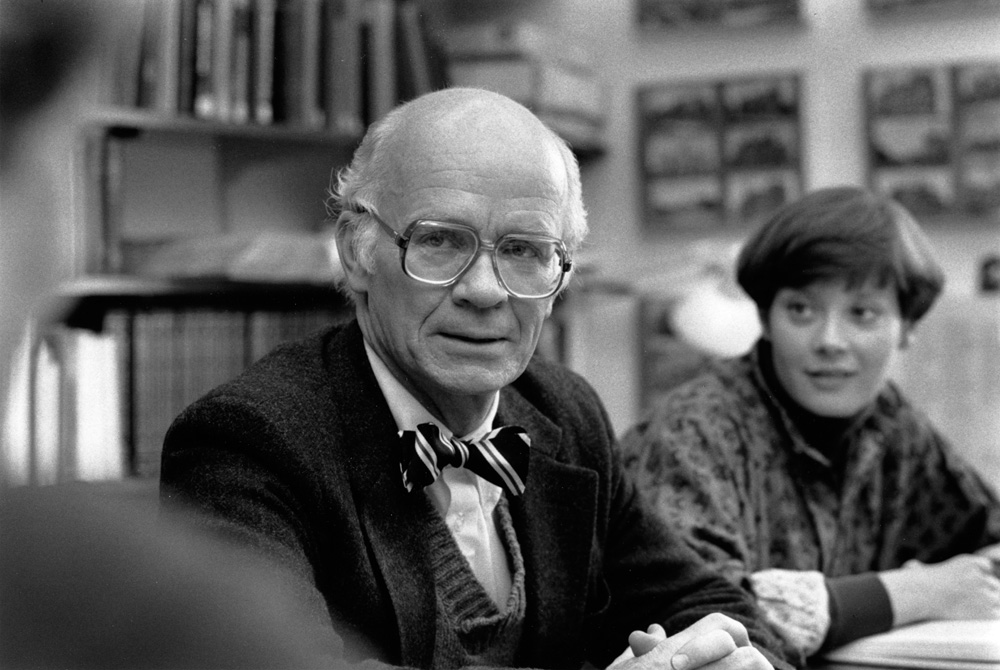

The Fawkes project is led by two computer science Ph.D. students at Security, Algorithms, Networking and Data (SAND) Lab, Emily Wenger and Shawn Shan, who work with UChicago Ph.D. student Huiying Li and UC San Diego Ph.D. student Jiayun Zhang. They are advised by the codirectors of the SAND Lab, professors Ben Zhao and Heather Zheng, in the Department of Computer Science.

Fawkes was inspired by the concept of model poisoning, a type of attack in which a machine learning algorithm is intentionally fed misleading data in order to prevent it from making accurate predictions. Usually, poisoning attacks take the form of malicious virus used by computer hackers. Shan asked, “What if we could use poisoning attacks for good?”

Crafting an algorithm that tweaks photos in ways that will confuse detecting systems but remain unrecognized by humans requires striking a delicate balance. “It’s always a tradeoff between what the computer can detect and what bothers the human eye.”

Wenger and Shan hope that, in the future, people will not be identifiable by governments or private actors based purely on images taken of them out in the world.

Since the lab published a paper on their program in Proceedings of USENIX Security Symposium 2020, their work has received lots of media coverage. Wenger says that some of the coverage has made Fawkes seem like a more potent shield against facial recognition software than it actually is. “A lot of the media attention overinflates people’s expectations of [Fawkes], which leads to people emailing us… ‘why doesn’t this solve all our problems?’” Wenger said.

Florian Tramèr, a fifth-year Ph.D. student in computer science at Stanford University, has written that data poisoning software like Fawkes gives users a “false sense of security.”

Tramèr has two main concerns: Fawkes and similar algorithms do not account for unaltered images people have already posted on the internet, and facial recognition software developed after Fawkes can be trained to detect faces in images with the distortions applied.

In their paper, Wenger and Shan address the first problem by suggesting users create a social media account with masked images under a different name. These profiles, called “Sybil accounts” in the computer science world, mislead a training algorithm by leading it to associate a face with more than one name.

But Tramèr told The Maroon that flooding the internet with masked images under a different name isn’t going to help. “If Clearview [a facial recognition system] has access to the attack (Fawkes) then [it] can easily train a model that is immune to the Fawkes attack.”

Tramèr is unconvinced that Fawkes could provide them a strong enough shield against recognition software that will be developed in the future. There is “no guarantee of how strong this perturbation is going to be in a year,” he said. Attempts to render one’s face undetectable in images could be thwarted by training next year’s algorithm on a set of photos masked by an old version of Fawkes.

However, Tramèr does believe that wearing a mask in a public space could evade detection, because the advantage always goes to the party playing defense. “If there is a facial recognition at the airport, and you know it’s there, then every year you show up at the airport, you can come with a new mask that is better than the year before.”

However, Tramèr believes that the use of facial recognition software can only be limited via policy changes. He seemed moderately hopeful and cited companies like Microsoft, Amazon, and IBM, which have said they will not sell the facial recognition software to law enforcement agencies. Among these companies’ concerns is the fact that these models have demonstrated less accurate recognition of darker-skinned faces than lighter-skinned faces, which could enable police brutality towards Black people. Still, other companies, like the doorbell camera company Ring, continue to collaborate with police forces.

Wenger and Shan said there would always be a new facial recognition model that could trump their latest masking attempt. Still, they think Fawkes and other software that make facial recognition more difficult are valuable. “We’re increasing the costs for an attacker. If no one proposes the idea, however imperfect, nobody ever moves forward.”