The University of Chicago Police Department (UCPD) is among the largest private university police forces in the country. Its officers have the same authority to arrest, issue citations, and carry firearms as municipal police.

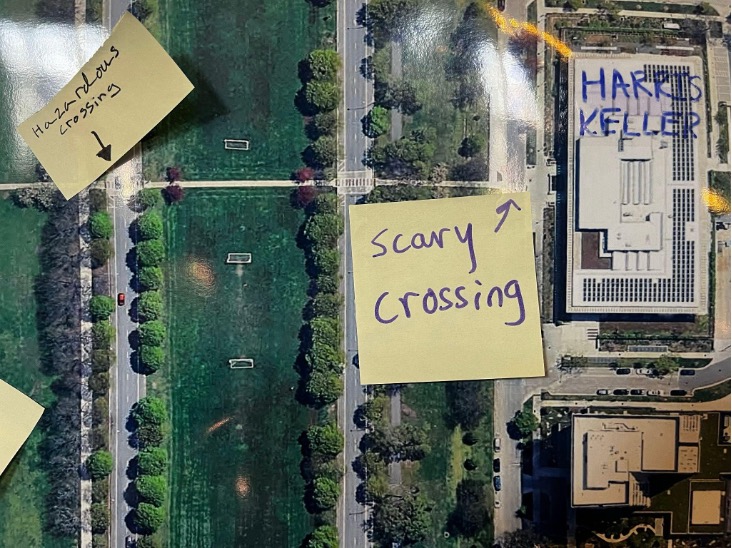

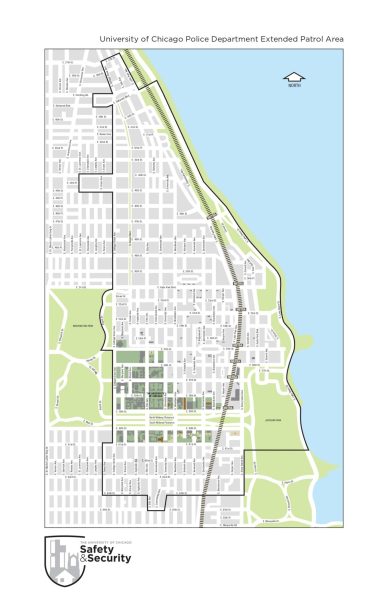

Created in the early 1960s amid fears of rising crime around campus, it now patrols 6.5 square miles across Hyde Park, Kenwood, and Woodlawn—an area nearly 20 times larger than the University’s campus itself. This area is shared with the Chicago Police Department’s (CPD) 2nd District, with UCPD serving as a primary responder for calls on campus and University property. UCPD can also respond to calls throughout its extended patrol area, though CPD acts as the primary law enforcement agency.

The department employs about 100 full-time officers certified under the same Illinois Law Enforcement Training and Standards Board requirements as municipal police.

How does UCPD’s patrol area compare to other private campus police jurisdictions?

Nearly 1,300 institutions of higher education in the U.S., both public and private, have campus police forces.

Private peer institutions of Yale University, Duke University, Wake Forest University, Tulane University, and Rice University each operate a private campus police force with state-delegated arrest authority, balancing public policing powers and private governance. Each university police force operates under its state laws, and all were created between the 1940s and 1970s—a period when many private universities sought formal policing powers in response to urban unrest and campus safety concerns.

UCPD’s patrol area, which includes tens of thousands of non-University residents and in recent decades expanded to include UChicago’s charter schools, is one of the largest patrol zones in the nation—larger than Duke’s or Rice’s and comparable to Yale’s New Haven jurisdiction, which spans roughly four square miles.

What information is UCPD obligated by law to release?

Unlike the public Chicago Police Department, UCPD is not required to follow Illinois’s Freedom of Information Act (FOIA), which grants individuals access to public records.

Instead, the University selectively publishes data about its activity, including daily crime and fire incidents, traffic stop data, field interview cards, quarterly crime trends, annual complaint summaries, timely warnings, and crime bulletins. Arrest records are “available upon request” from the department. There is no direct equivalent of a FOIA portal through which individuals may obtain public records via written request.

The University does not disclose information related to the budget allotted to UCPD activities and does not publish online use-of-force data, body camera footage, or internal investigation outcomes, which has led to criticism from some Hyde Park and Woodlawn residents who live within UCPD’s jurisdiction.

Illinois law does not clearly define transparency obligations for private universities, creating a gray area that places UCPD largely outside of statutory oversight.

Why isn’t UCPD subject to Illinois’s FOIA?

UCPD derives its authority from the Illinois Private College Campus Police Act, which grants private universities police powers without explicitly defining transparency obligations.

Illinois is an outlier in this respect. Yale, Tulane, and Rice are all subject to FOIA laws in their respective states. In 2008, Connecticut courts explicitly ruled Yale’s police a public agency for records purposes, and North Carolina’s General Assembly later codified the same principle through General Statute 74G-5.1 in 2013. The Texas Legislature likewise confirmed Rice’s duty to disclose police records. In Louisiana, Tulane remains in a legal gray zone; its police log is accessible only on site as required by the federal Clery Act, but it limits access to a physical kiosk.

In 2015, amid debate over a proposed bill that would have subjected UCPD to FOIA standards, UCPD began to include traffic stops and field contacts in the information it makes publicly available.

At the time, the University said its disclosures “go beyond the requirements of Illinois law for police departments at private institutions.”

How does UCPD differ from CPD in officer training and the ability to make arrests and exercise force?

UCPD officers, unlike UChicago’s safety ambassadors, are required to receive the same basic training that state and municipal police officers receive. As a result, officers are able to carry out many of the same responsibilities. They can arrest, cite, detain, and release individuals, enforce traffic laws, and refer criminal cases to the Cook County State’s Attorney. Officers are authorized to carry patrol rifles, which is consistent with many police departments around the country.

“They can write you a ticket. They can arrest you,” Cora Beem, training officer for the Illinois Law Enforcement Training and Standards Board, said in an interview with WBEZ Chicago in 2014. “They can counsel and release you, so yes, they’re real cops.”

UCPD can only, however, conduct citywide investigations outside of its patrol area for criminal offenses over which it has primary jurisdiction, such as crimes committed on campus.

How transparent is UCPD about its spending?

The Department of Safety & Security’s annual reports, which UChicago has published online since around 2012, describe unit highlights, technology upgrades, and reference national benchmarking surveys such as the Security Benchmark Report. However, these reports aggregate spending for the entire Department of Safety & Security and do not list UCPD-specific expenditures or staffing costs. Older reports, like the 2016 annual report, mention efforts to “streamlin[e] services and contain[] costs” but do not provide a dollar figure for the police department itself.

Practices at peer institutions vary widely. Duke and Yale include partial budget details in institutional financial disclosures, while Rice, through Texas’s open-records law, provides access to departmental contracts and salary ranges. Tulane and Wake Forest disclose only Clery Act safety statistics, which track campus crime by category but omit financial or personnel details.

Is UCPD conduct subject to external review by the city or state?

An Independent Review Committee (IRC) oversees complaints made against UCPD officers. The IRC was founded in 2005 and includes faculty, community members, and students appointed by the provost. It reviews misconduct complaints and issues annual summaries of its findings. UCPD is treated by the city as a non-governmental police agency governed by the Illinois Private College Campus Police Act, meaning it falls outside the jurisdiction of Chicago’s civilian oversight bodies, which are limited to City departments and CPD officers.

Unlike municipal departments, whose policies are subject to oversight by elected officials and bodies like the Civilian Office of Police Accountability, UCPD accountability rests solely with the IRC and University administrators. This structure, transparency advocates argue, leaves unaffiliated residents without formal avenues to review or contest police actions on public streets.

Examples of contested UCPD encounters include traffic stops and arrests of local residents, later publicized by community groups such as #CareNotCops.

Why has UCPD’s authority been controversial?

UCPD’s semi-public jurisdiction has been contested since its inception. When the University first established the department, City officials granted it arrest powers under an arrangement that allowed the University to supplement CPD patrols in surrounding neighborhoods. The Illinois Private College Campus Police Act later codified those powers, giving UCPD legal parity with municipal officers but without attaching any new transparency obligations.

Over time, especially in the 1970s and 1980s, UCPD’s patrol boundaries expanded amid the University’s investment in surrounding property and concerns about neighborhood safety. Its northern reach now extends near the University’s charter school campus at 37th Street. By the early 2000s, the University described UCPD’s role in terms of a “partnership” with CPD and neighborhood safety, but organizers have pushed back, arguing that the model gives the University policing power over non-students without real community control.

Yale and Duke have faced similar tension with neighboring communities, though open-records access in those states has allowed for greater public scrutiny of incidents and spending. In contrast to Rice’s open-records portal, Tulane’s on-campus access rule limits external review.

Calls to make UCPD subject to FOIA intensified after the 2018 police shooting of UChicago student Charles Thomas, during which the University described Thomas as having a mental health crisis.

Similar campus-police controversies have surfaced elsewhere: Yale’s 2019 off-campus shooting led Connecticut legislators to expand police-report access, and Duke and Wake Forest now release annual summaries of use-of-force incidents.

In Illinois, these efforts have stalled, and state law remains unchanged.

Could legislative reform lead to increased transparency from UCPD?

Illinois lawmakers, including former State Representative Barbara Flynn Currie (D-25th) and Senator Robert Peters (D-13th), have proposed multiple bills since 2014 to make private police subject to FOIA. The most recent, Senate Bill 1275, would have required private universities’ police records to be treated as public. The bill stalled in committee.

If adopted, such legislation would align Illinois with Connecticut, North Carolina, and Texas, where private campus police already operate under open-records laws.

Editor’s note, November 20, 9:53 p.m.: This article has been updated to correct information about UCPD’s jurisdiction in its extended patrol area, its ability to conduct citywide investigations, and the role of the Independent Review Committee.