What happened this past Friday night in the University of Michigan’s Power Center theater can’t really be called an opera, at least in traditional terms. But what became apparent during its duration was that the work is as much a mystery as it is an intense sensory experience.

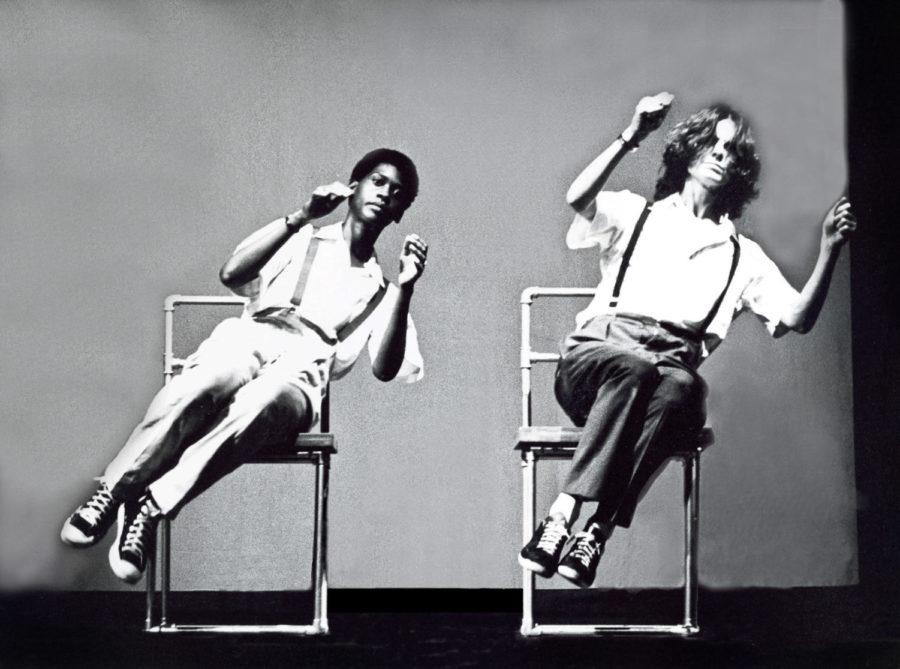

As the audience walked into the theater (thirty minutes late, on account of the bad weather), the performance had already begun. A group of singers, all dressed identically in grey pants, white shirts, and suspenders, were standing toward the right side of the orchestra pit. All were motionless, their clownish makeup highlighting bright faces frozen in concentrated stares. Robotically intoning numbers, mouths hardly moving, they seemed to be awaiting the arrival of the confused and excited visitors as they finished filing in.

This wasn’t the first time this unusual sight had greeted opera-goers. Philip Glass’s (A.B. ’56) revolutionary opera, Einstein on the Beach, ostensibly about the famous scientist (though it’s open to wide interpretation), debuted in New York in 1976. It’s been reprised twice, with the last iteration in 1992. New York City Opera commissioned a new production for 2009, but the economic recession abruptly halted those plans.

Fortunately, Pomegranate Arts, an indpendent production company from New York, decided to create an international production, bringing in original collaborators Glass, Lucinda Childs, and Robert Wilson. For the first time in twenty years, Einstein on the Beach was performed in its five hour entirety at the University of Michigan. A world-wide tour, starting in France, will soon follow.

Director Robert Wilson originally conceived the idea for Einstein; he gave Glass various set sketches and asked him to write the accompanying music. Glass wanted to do an opera about a historical figure, and the two men eventually settled on Einstein. Lucinda Childs was brought in for the choreography and did narration for the 1976 original. Still in previews, last weekend’s performance was, nevertheless, virtually flawless, despite the music’s inherent difficulties.

The opera is intentionally plot-less. A series of recurring images—a train to represent the theory of relativity, and an on-stage violinist dressed as Einstein—are the only references to the scientist’s life. There are no words, either. Glass’s music is instead set to numbers, with singers chanting the beat, or solfége. Because of the intense pace of the music, many of these sung words and sounds blend into a ritualistic chant.

Even the choreography is abstract. Childs’s own dancers are featured in two beautifully choreographed scenes, but all performers are essentially choreographed in some way. With stunning muscular control, both dancers and singers carry out specifically timed movements throughout the duration of the opera. In each scene, constant but slowly changing motions carried out by everyone on stage accompany Glass’s similarly hypnotic music, creating an ever-morphing tableau.

Because the opera is so long (five hours) and there’s no intermission, attention slips are not only inevitable, but intended. Like Einstein’s theory of time, this opera is relative. No one in the audience pays equal attention, as evidenced by the multiple comings-and-goings of the crowd. Looking up after a period of zoning out can make you subject to new discoveries—the train has moved, that man has sat down, the light in the background has changed color.

Perhaps one point of reference for the audience, even those unused to opera, is the spoken text. Unusual for opera, Einstein includes long strings of speech chanted over the music. Written by the poet Christopher Knowles, these texts include short phrases which are repeated over and over, changing slightly throughout, like the music. To avoid monotony, the cast took care to change their inflection when reciting these texts, lending new meaning and subtlety to almost every repetition. In one scene, a woman lying supine before a judge casually describes a “prematurely air-conditioned supermarket.” But when she rises and walks to the right side of the stage, she slowly changes into a criminal, donning a black suit and a gun, which she points at the audience. Her formerly innocent words about supermarkets and bathing caps now become menacing, her voice giving them a provocative flair that had not existed before.

At one point toward the end of the opera, the set turned into a two-dimensional picture of a building, a woman “seated” in a room behind it. The ensemble was playing its usual ascetic arpeggios when suddenly, saxophonist Andrew Sterman broke out into a stunning extended jazz improvisation; swirling harmonics and lines of music carried into the audience, augmented by speakers. His perpetual play was broken only by intermittent intonations from the choir, coming from somewhere backstage, or perhaps below. The audience, which had been coming and going (as allowed by Glass himself) during the previous scenes, suddenly sat still. Sterman’s saxophone created a palpable power and the onslaught of onstage colors seemed tangible. People were swaying, some tapping their feet; others stared at the stage as if into the void.

For an opera without any plot, without any intelligible flow or structure or meaning, the emotional impact was powerful. Glass’s objective, whatever it was, had been achieved.