There is no doubt that our health care system is in crisis. Health care is far from efficiently organized, and many are left uninsured or without access to care. This is especially visible on the South Side, whose residents have consistently poorer health outcomes and access to health care than those in other parts of the city.

Such health disparities have been the driving force behind many community-organized campaigns by groups such as STOP (Southside Together Organizing for Power) and its youth wing FLY (Fearless Leading by the Youth). These campaigns aim to improve access to care by trying to get the government or the University of Chicago to open new facilities and prevent the closing of pre-existing ones.

The most prominent of these has been the ongoing campaign to get the University to reopen its Level 1 trauma center. The next protest by FLY, a march scheduled for May 12, bears the name “They Don’t Really Care About Us: March Toward a Trauma Center.”

Though we could argue extensively about how much the University as an institution is actually committed to helping residents of the South Side, the issue of a trauma center is more complex than the story organizations like FLY would like to tell: that of a rich, immoral university refusing to share its resources with those who suffer around it. Ultimately, those who campaign for the trauma center overlook the reality of its relative inefficiency in improving the overall health of South Side residents as compared to measures that would improve access to basic health care and preventative measures.

We would like to believe that no price can be put upon a human life. However, in health care this is exactly what we must do; there are limited resources and a great many people in need. In order to maximize the effect of our resources, we have to dispassionately examine how these are utilized and what they accomplish.

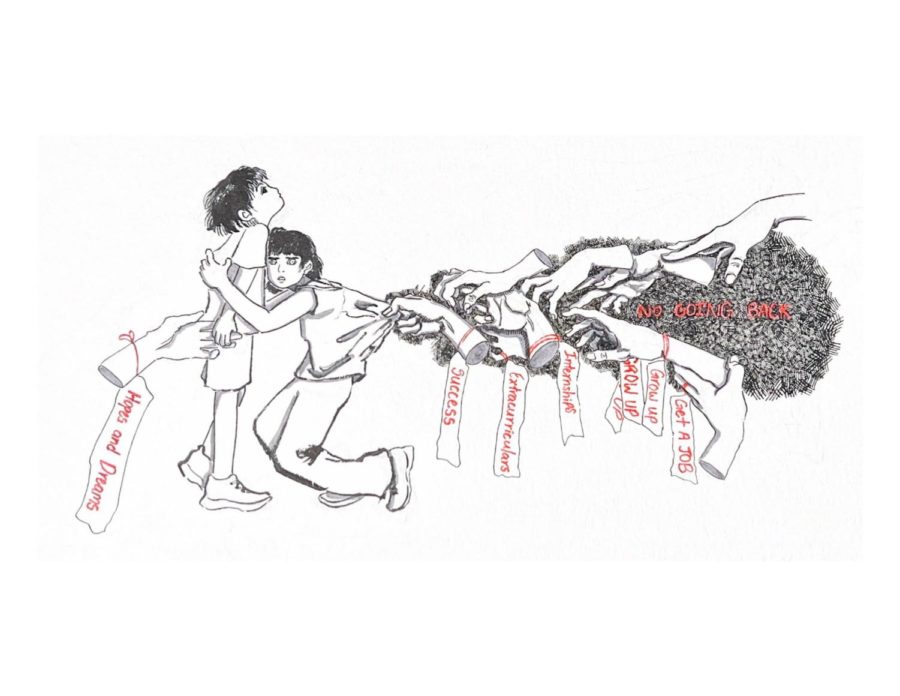

There is something difficult to swallow about examining issues that affect people so profoundly in utilitarian terms. After all, every person who needs medical attention is someone’s son or daughter, mother or father, spouse or best friend. Damian Turner, one of the founders of FLY who died after being shot and taken to the Northwestern trauma center, is just one example. How is it fair for the University to tell his mother that it would have been too expensive for him to live?

This feeling of injustice is strengthened by the fact that there are so many people whose fates are not determined by how much the medical establishment is willing to pay. The University abounds with the wealthy and the well-insured. I have always been able to get the health care that I need, and that is an ability that many on the South Side go without.

Unfortunately, we are stuck within the bounds of an often unjust and dysfunctional system. There are not enough resources, and those resources are not allocated equally. Part of the problem that we see in the case of trauma centers is that private institutions (like the University) are being asked to fill the gap where our public health care system has failed. Repairing the disorganized state of the American medical system is far in the future, if it is to happen at all. At present, we must concentrate upon the resources that are available and how to best use them.

This is where community activists seem to lose track of wider health issues and become too caught up in the symbolic value of a trauma center. It is debatable what should be done from a moral standpoint; however, as a private entity concerned primarily with academics and other institutional interests, the University is only going to invest a certain amount of money in improving the health of the neighborhoods that surround it. Knowing this, community and University leaders must decide whether an expensive trauma center is really the most effective way of using this finite amount of money.

The South Side has many other pressing health issues that are cheaper to address and affect more people than those that would be affected by the presence of a Level 1 trauma center. Community leaders should be calling for smaller, publicly visible, and focused programs that are both more likely to gain University funding and improve health in the long term.

In a survey published by the Chicago Department of Public Health, Woodlawn, the neighborhood just south of the University, rated poorly in six of the nine behavioral risk measures examined, including rates of smoking, exercise, and health care coverage. There were also higher-than-average rates of low infant birth weight, mothers receiving no prenatal care, and teen pregnancy. In aggregate, these risk factors have a dramatic effect: Life expectancy can be as much as 15 years shorter for those who live on the South Side than for those in predominantly white, middle-class areas of the city.

What we see here is unequal access to health care on a massive scale. These systemic problems cannot be solved by the creation of an expensive trauma center that would address only a small segment of the health needs of the South Side. The closure of the Woodlawn Mental Health Clinic is an example of an alternative issue brought forth by activists that the University could have addressed in order to impact health care access within the community.

If community leaders and the University are serious about improving the health of residents of the South Side, then the millions it would cost to maintain a trauma center could be better spent on much-needed but less dramatic measures, such as health education, disease screening, vaccinations, and care for children. The lack of a Level 1 trauma center on the South Side is deplorable, but the lack of access to basic care is a far more pressing issue.

Maya Fraser is a second-year in the College majoring in sociology.