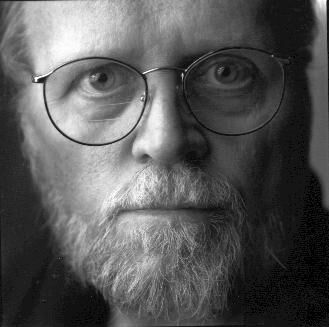

Ron Silliman, American poet, has written and edited over 30 books of poetry and had his work translated into 12 languages. Silliman is often associated with the language poetry movement. He has been working on a single poem, “Ketjak,” since 1974. He will read this Friday at 6 p.m. at the Poetry Foundation. The Maroon sat down with Silliman to talk about his career and upcoming reading at the Poetry Foundation.

The Chicago Maroon: Can you tell us a little bit about what you’ve been up to lately?

Ron Silliman: Since I retired last year, I have been mostly working on the transition to retirement. One of the first things I’ve done are poetry reading tours in places where people have asked. The European tours are coming up right after the reading in Chicago this Friday.

CM: How are you connected with the Poetry Foundation and Poetry Magazine?

RS: I’m currently 65 years old, and I started writing around 1965. I went around telling people I was a poet for a year or two before I started writing, even though most people do it other way around. I started publishing immediately—in fact, I published the first poem I ever wrote. And, a short time later, I had a poem accepted by Poetry, which was and continues to be one of the hardest publications to get into, because practically everyone in the world wants in. The Poetry Foundation has expanded its mission since they received a multi–million dollar donation from the Lilly family. They’ve become much more pluralistic and democratic, and they’ve gone through some very interesting changes in the past decade. Being more lax has been one of the positive side effects of their having more money. It brought them up into the contemporary poetry world in a way they hadn’t been.

CM: How did Friday’s reading come about, and what do you think you’ll share?

RS: I think I’m going to read the poem I published all those years ago in Poetry, which I’ve actually never read in public before. I think it was the January 1969 issue. I hold the record for having gone the longest between appearances in the magazine, because my next publication was in 2010. They published a poem of mine called “Revelator,” which received the Levinson Prize [a prize Poetry awards to one poet each year]. That put me in a roster with Carl Sandburg, Wallace Stevens, Robert Frost, and other people who I wouldn’t usually put myself in the same room as. Anyways, I held this record, and when my wife and I were out visiting Jesse [their son] sometime last year, we went and visited the Foundation, too. In the process of that visit we talked about having a reading, and this is the product of that.

I think I’ll probably be reading something old, something new, and something from in between. I was thinking I’d read my two contributions to the journal, and in between the two—well, I’ve been working on the same poem, “Ketjak,” since 1974, and it’s gone through a lot of stages, by which I mean that I really visualize them as Russian nesting dolls. The first stage came to be called “Age of Huts,” and it was a quartet of poems. I will be reading the opening section from one of those poems. The second stage was called “Tjanting.” A tjanting [pronounced “chanting”] is actually a writing implement like a pen used in Indonesian batik, for lettering or line work. The third stage of this poem is called “The Alphabet.” I worked on it for about 25 years, and it’s about 1,000 pages long. I think I might read something from the first portion of the next stage of the project, too.

CM: How did you start working on such a huge scale with poetry?

RS: Well, it’s because I’m more interested in poetry than in poems. Actually, poems are relatively uninteresting, because their scope is restricted. So I’ve been trying to do the opposite by trying to write a poem first as long as a short story, then as long as a novel, then as long as War and Peace, and now, hopefully, as long as the Encyclopedia Britannica. I keep trying to change the scale on which one can produce poetry. I’m not the only person working on the long poem, but that’s what I’m primarily doing. Even when I was just a teenager and getting started in poetry, I knew I wanted to do a long project someday.

One of the things I’ve learned is that most people know everything they need to know about poetry the minute before they start writing. Learning to write is about getting rid of the mythology from our culture about what writing is and what poetry is. Much of learning to write is unlearning rules, like high school grammar. It has to do with really learning to strip away those layers to get to putting down on paper what you know, see, hear, and think, all of which help you arrive at how you feel.

CM: You run one of the most successful poetry blogs on the web. How did you decide to get started with it?

RS: Working on the student paper when I was in college was an important thing I did—it actually led ultimately to my blog. But I got the idea from a nephew who was a student at a small conservative college in Michigan. He was posting his philosophy papers on the web so he and his friends could talk about them, and that was when I realized that blogs could mean more than teenagers gossiping about dating. Now, with Facebook, blogging isn’t even what it used to be. My blog is about to turn 10 years old. That makes it ancient. I’m going to have to decide if it’s the best form for what I want to write about critically, going forward. One of the things I was looking for was a mechanism for communicating with other writers, for talking about my writing. In the past, that had meant going through the gated community of academic journals. I’m much more interested in the kinds of communities that one finds around the Beat or New York School poets, who don’t have to do with the universities. I was sort of thinking that if I had 30 readers a day my blog would be completely successful. I had 140 readers on my first day, and that sort of blew me away.

CM: What about the tension between print and web publication in general? Does technology pose a threat to poetry?

RS: This idea that print has disappeared is ridiculous. As my wife says, “All you have to do is look at my basement and you’ll know where it’s gone!” It’s true that there are real changes occurring that are as profound as the invention of the Gutenberg printing press. The real implication of this in the short run has really been one of making the world much smaller and creating more forms of access. The national boundaries that existed for poetry when I was young have become far less imposing than they were even 25 years ago. For example, my next reading after Chicago will be in the Netherlands, and then Belgium, then the Yucatán. In that regard, being an English-language poet from an insular, working-class family in the San Francisco Bay area has hardly prevented my work from being successful. It’s still going through a lot of changes.