In 1968, University of Chicago economist Gary Becker solved the problem that had plagued law enforcement officers, politicians, and city planners since, well, the dawn of civilization: How do we stop criminals from committing crimes, and is stopping crime even desirable? Becker’s paper, “Crime and Punishment: An Economic Approach,” looks at criminals as rational individuals, just like anyone else. Criminals, like ordinary citizens, seek to maximize their own well-being, but through illegal instead of legal means. Radical in its time, the Becker Model has stood as an authoritative theory on crime since it was published.

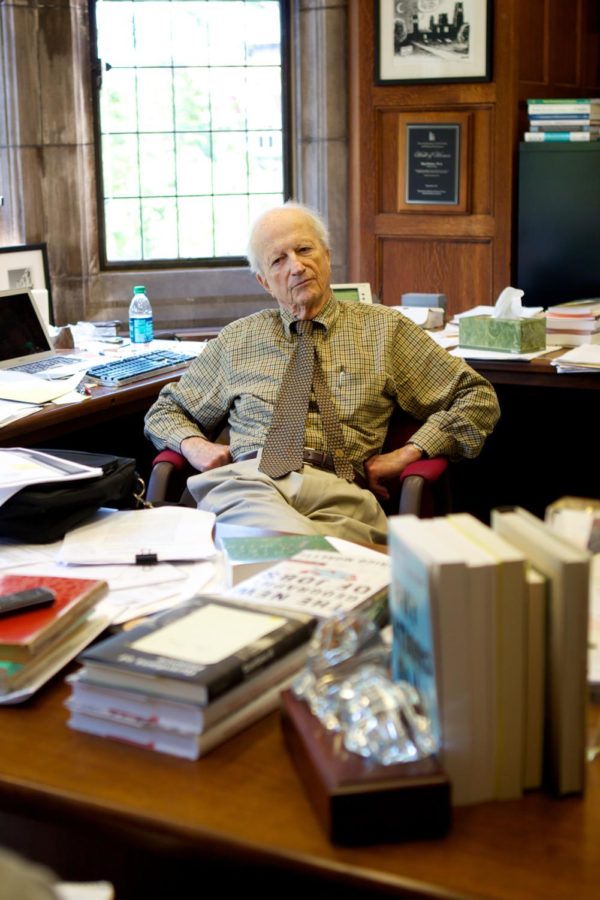

Becker was also the first economist to apply economic models to non-market social structures (think Freakonomics), an achievement for which he was awarded the 1992 Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences. Becker’s current research focuses on the repercussions of an increase in students pursuing higher education, the value of increasing life at old age, and the various intricacies of human capital. Professor Becker sat down with GREY CITY to discuss misconceptions about crime, the effects of drug legalization, and whether or not it’s possible to stop crime.

GREY CITY: So I understand that your first paper was inspired by a particular event. Can you tell us what that was?

Gary Becker: I was teaching at Columbia University and was driving to an oral exam with Ph.D. students. The question [I asked myself] was, “Should I park closer in a spot that was illegal, or should I park in a lot which was somewhat further away?” So I had to make a calculation: What was the likelihood that I’d be caught if I parked it down the street versus the time, the money, that would be lost by parking further away? I decided to park on the street, and since it was an oral exam, the first question I asked the student when my turn came to examine him on price theory was how he would handle a problem of this type…. I asked a lot of questions, and they didn’t do very well on it [laughs]. After I came out of the exam, I figured this is a really good problem to work on, so I started thinking more systematically about it.

GC: As we all know, you ultimately came to the conclusion that criminals are just like any other in- dividuals, facing daily problems like your parking situation. That’s a pretty radical thought: People like to think that criminals are acting with some ulterior motive that can’t be understood. When you presented this idea in Crime and Punishment, how did people react?

GB: A lot of hostility among many people. Some economists found it simpatico, so to speak. A num- ber of economists and certainly many non-economists—sociologists and psychologists—found it really ill in way of thinking about the problem. It’s still controversial, but it became less controversial over time as more and more work was done on crime by economists and others, and as the notion of de- terrents—that you can deter people in a variety of ways: by punishment, by education, by giving them better alternatives—became much more acceptable.

GC: The paper comes to a rather interesting so- lution, that punishments should be limited almost exclusively to fines. That’s not very intuitive.

GB: It’s acceptable to fine as long as people have the money and are not what we call “judgment proof.” So if you commit a murder, maybe no fine would compensate society for the damages done by that murder. A fine would be determined by how much harm you’re doing as a result of your actions. A murder would have an extremely high, maybe even infinite, value on it, and even very wealthy people would not be able to meet that price. If they can meet the price, then you have to deter it in another way or in complementary ways—that’s why we think of imprisonment, probation, things of that type.

Fining has a great advantage. If you’re a criminal and you pay me (as the government) a fine, then I’m getting compensated. On the other hand, say I send you to prison; then you’re giving up something, but I’m also giving up something since I have to have guards and money and so on to take care of you. So that’s a really bad form of punishment. Prison may be inevitable, but you try to use a more effective punishment first if you can. A lot of activity we punish with fines. You drive too fast; you get a fine. A company pays less than minimum wage; they get punished with a fine. But they’re not always useable…and in those situations you have to sup- plement them with real punishments, which have a real cost to society too. You still want to punish the criminal, you still want to deter the action, but it’s going to cost you something.

GC: Is it possible to eliminate crime entirely?

GB: It may be possible, but I’m not sure it’s desirable. To get people upset, I like to say that there’s an optimal amount of crime. We might be better off in a society where everyone was law-abiding and wasn’t willing to violate any laws, but is it worth it to try to eliminate all crime? You would have to make the punishments very severe. Not only fines, but imprisonments and so on…. It’s not worth it to eliminate all crime; it’s just too costly.

So you do a balance. That’s what economics is all about: balancing incentives, balancing the marginal advantages of reducing crime by one unit versus the cost to society of doing that. And that balance will generally fall [where there are still some criminals left in society]. It used to be said that there was no crime in communist China, and the reason there was no crime was that the government had such close surveillance on everybody…. Most people don’t want to live in that kind of society.

GC: So, let’s say you’re the chief of police and you could institute any policies that you wanted. What would be the optimal policies, say, for the city of Chicago?

GB: It depends on the type of crime. There’s not one policy for every crime…. You mostly want to deter the most serious crimes. You don’t want to sentence people to 10 years in prison because they went 50 miles per hour in a 40 mile per hour zone…. If I was police chief, if I could control policy…I would legalize the sale of drugs. We’re putting a lot of people in prison for that, and we’re crowding our prisons. I would say it’s not worth it, in terms of the cost to society and to the individuals being punished. We should move in the direction of legalization.

GC: The counterargument to legalizing drugs is that you’re giving drug usage the moral stamp of approval.

GB: Well, we legalize a lot of things we don’t necessarily like to do. A lot of people vote for legalizing divorce, even though they wish people would stay together. They recognize that there is a cost you’re imposing on people. Many people might say [that] in a world where, by making drugs illegal, you could costlessly eliminate [drug usage], a lot of people would favor that policy. I don’t deny that…. The problem is that that’s not the world we live in. We’ve tried a policy of punishment since President Nixon started a War on Drugs in the 1970s. It’s almost 40 years ago now, and it has not been a successful policy…. We’re putting a lot of police on it. We’re sending people to prison for what are relatively minor crimes com- mitted against other people…. I had a teacher, Frank Knight, who was a great economist, who taught at the University of Chicago, who used to say, “Principles conflict.” You may have a principle: You don’t want drugs because you don’t think it’s moral. On the other hand, you don’t want to have all these costs from drug enforcement policy, so you have to balance those two principles.

GC: Another focus of your research is on the economics of discrimination. Chicago is one of the most segregated and discriminatory cities in the country. Does this contribute to crime? Are the two interlinked?

GB: It’s controversial how much segregation contributes to crime. What is true is that because of segregation, minorities commit a disproportion- ate share of the felonies, and the victims are usually other minority members. Segregation does affect who’s the victim of a crime…[but] I think the most serious problem about crime—and maybe it’s related partly to segregation and minorities and discrimination—is that so many minority members drop out of high school, and we know that those are the people most likely to commit crime. So if we can get a better school system, they would find that their legal opportunities are better than their crimi- nal opportunities, and they wouldn’t commit crime. That’s the worst thing we’re doing to minorities in Chicago and in many other places as well.

GC: So your response would be to give them other incentives, to increase the side of the equation that deters them from committing crime.

GB: It turns out that, for most people, trafficking drugs doesn’t pay very well. But even law-abiding people on the street are making around minimum wage. We need to reform our educational system so that these people think to themselves, “I can do better than that by finishing high school and get- ting a better salary. I don’t have to risk going to pris- on. And I’ll make more money.” People will choose [to finish school]… We will reduce the amount of crime that way. I think that’s the worst thing we’re doing to minorities in Chicago and elsewhere—that we have such a high dropout rate. Now is that discrimination? It’s more complicated than that. [The problem is] probably not going to good enough schools. It’s also probably weak family structures, which are much harder to attack. But certainly the school system we can make better, and I think we should give high priority to that.

GC: You won the Nobel Prize in 1992 for applying economic principles to non-economic fields. What inspired you to think this way? You were one of the first to do this.

GB: When I was in college, I was interested in social problems. I majored in economics be- cause I was also interested in mathematics, and economics attracted me because of the mathematics. And then I thought, “Well, maybe I can use my mathematics to help with social problems.” When I was a senior in college, I got a little discouraged with economics because it seemed not to deal with real problems. I thought about going into sociology at that time. But I found sociology too difficult. So I decided I’d stay with economics, and fortunately I came to the University of Chicago as a graduate student, had some great teachers who inspired me and showed me that economics is a powerful tool for understanding the world, and that really made a great difference in my life. But I had this interest in social problems even before coming to Chicago; I just didn’t know how to do it using eco- nomics. That’s what I learned when I came here.

GC: Switching gears a little bit, the NATO conference was in Chicago this past weekend, and one of the arguments against having the conference was that it would bring a lot of crime. Same thing with the Olympics a couple years ago. Do big events always necessarily have to bring crime, and are those big events worth having if there’s always going to be crime?

GB: Well, whether it’s worth having is…[laughs]. People say Chicago got a lot of prestige from host- ing the NATO event. The reason it brings crime is that we divert a lot of our police to the event…. If I was a criminal, I’d say it was a pretty good time to commit a crime [laughs]. Police aren’t around: If I want to drive faster on the highway, I’ll do it. And I was on the highway Friday evening just before they were closing it down. I was on the highway going to a dinner party on the North Side, so I had to go through this stretch, and people were driving fast. I mean, the likelihood you would be apprehended at that time was much, much lower.