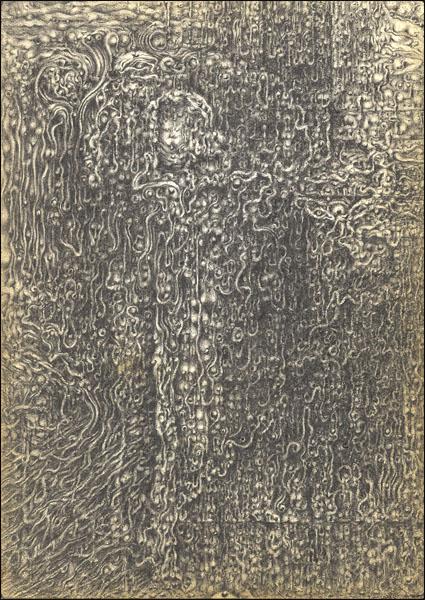

Tucked into a narrow hallway in the DePaul Art Museum, a truly breathtaking collection of drawings hangs in a bare, ominous silence. This hollow corridor could not present a feeling more in contrast to that evoked by the works themselves, which seem to depict the very essence of fluid life. The pieces presented in the exhibit, “The Nature Drawings of Peter Karklins,” are filled with forms that emerge from and dissolve into one another. They drip, ooze, and swell, as breasts lengthen into sperm, which bleed into waterfalls, which cascade into lumps of slate. The tiny drawings are grotesque. They are manic, chaotic, even horrifying. However, beneath this ugliness pulses something so beautiful that it is almost sublime. The drawings, none of which measure more than seven inches in length, confront the viewer with an intricacy and imagination that, to be quite honest, I have rarely seen in another work of visual art. Each drawing is a ghastly microcosm in which the audience recognizes, both greedily and shamefully, its own image.

I spent more than an hour in this tiny hallway, which seemed, as I moved from piece to piece, to deepen and expand. I suddenly felt strangely helpless, but not because the drawings seemed out of control. On the contrary, one of the first things that struck me about the show was Karklins’ incredible capacity to control the movement and structure of his work. This obsession with control was manifest in Karklins’ habit of documenting on each piece the times and locations at which he created the drawing, and sometimes even the music he was listening to. I felt vulnerable because of the way the pieces de-categorize life and even render it anonymous. There is no distinction between man and woman, between human and animal, between animal and nature. There is no sense of depth or background, but, instead, boundlessness that seems to extend past the worn edges of the pages.

Karklins’ drawings, largely created during his night shifts as a security guard, captured the attention of both DePaul philosophy professors and the University of Chicago Press, which recently published a book bearing the same title as the exhibit. I got to sit down with the artist to discuss his work.

Chicago Maroon: The name of the exhibit, and the book that the University of Chicago Press just put out, is The Nature Drawings of Peter Karklins. What role did nature play in the creation of each piece?

Peter Karklins: Of course I’m influenced by nature; I’m influenced by everything I’ve ever seen…’self-’ anything is just wrong. ‘Self-’ anything is not possible. And, uh, ‘self-taught’—who are you kidding? It’s just—it’s just an impossibility…If you look at the work [The Great Mother, An Analysis of the Archetype by Erich Neumann and Ralph Manheim] carefully, you will see the feminine V happening all the time throughout the compositions. Then there are trees that also look like the female form, like the ghost of a female form in a forest…and since my work is clearly not about anything but everything, these things appear in the context of a forest; they kind of peek out of a forest and disappear back into the forest…I was looking at shots of the Amazon rainforest taken from the river on the shore of the jungle, where the jungle just was growing out of the river, and I was looking at the water on the bottom of the jungle growing up, and I was looking at the trees—the way they were growing up the images on my computer—and said, “Hey, you know, I’ve never been on the Amazon and I’ve never seen this before, but there’s a strange resemblance to my little drawings.”

AH: I’m wondering about the process—how did each drawing come about? That is, did you have any idea what the finished products would look like, or did they just sort of develop over time?

PK: Oh, god no. Oh, god no. Oh I have no idea. I start by scribbling. And then usually it looks like a human figure, of a sexual nature, that turns into a landscape. And then out of this figure grow all kinds of things, that turn out to be forests or maybe little indications of animals and you can’t tell whether those are the tears of God, or if they’re seminal fluids, or if they’re rain, or heavenly water fructifying the earth…I don’t start with symbolic ideas, or intellectual concepts. They happen to me. I start by drawing, and then I react to my little compositions physically—I squirm and I move and I growl and I groan. Thank God I’m doing this in the middle of the night when nobody can see me; they’d think I’m totally nuts…I don’t do the compositions intellectually, I do it bodily. I squirm and I worm and I move my body—this thing now has movement, this line moved me that way, so I go to the right and then I go back to the left and I bob up and down like a boxer in a ring. The ideas are just incidental; I’m basically concerned with getting the composition to sit right on the little piece of paper.

AH: That actually sort of leads me to my next question: the drawings are remarkable for many reasons, but most notable is their scale—why did you draw on such small surfaces?

PK: I found a beautiful young lady and had three beautiful daughters and I got a building, and then I went out of business and lost my marriage and my wife took my children away. I ended up unemployed, I was dirt poor, and I had no money. So I went to the Jewel Osco, got a little scratch pad, and I started making these little drawings. And then, I was kind of homeless—kind of borderline homeless…a friend of mine…said he had a spare bedroom, so I moved in there with my dog and my two cats, slept on the floor with my dog, and worked on my little artwork. So, I was in a confined space. And then, of course, to pay child support, I got a job as a security officer on the night shift. And then I sat in my little corner, I carried my artwork around in my pocket, and I would draw on the train and I would draw on my security post. And most of the work was done at night on trains or railroads maybe, sometimes standing guard duty in front of a building, holding the paper in my hand and just drawing as if I were drawing on my own hand…I was fascinated by Freud and Jung because of the subconscious. In other words, another world other than the one that was in front of me, which I hated very much. So I turned to the subconscious, I loved the surrealists, and I took the surrealists seriously and lost my sanity and ended up in a hospital. And it was good for me; it was a growing thing. And that way I got to know a great psychiatrist. I would take my artwork to him and then point to these things… and he said, “Yes, Peter, it’s there,” but he wouldn’t dwell on it—he stayed away from it. He wouldn’t touch it… I always was a great hater of the world. A great lover of creation, but hater of this world.

AH: The passage of time seems to be an extremely important idea in your drawings. Why did you document your work time so meticulously?

PK: It’s not meticulously, it’s compulsively…Several reasons, and one obvious reason, which would be the most immediate one. I was working at a security post, so date and time—you always write down. Date, time. Always, you know, date, time, what’s going on. It’s called your DAR, Daily Activity Report. And it’s nothing…I was born January 27, 1945. That’s important to me. It also happens to be Mozart’s birthday. That also happens to be, almost to the hour of my birth, when the Red Army liberated Auschwitz. January 27, 1945… So dates and times are somehow important to me, maybe for reasons I don’t understand myself. And then I had heard that in the Christmas battles of World War I, several Latvian regiments stopped the German army while the Russian army ran. The earth was frozen…They mounted granite pillars at the location that the regiments went into action, and there were dates and times on there. To me, art is war. It is a conquest of consciences. So I don’t think that my date and time, and relating it to all the regiments going into action, is just a silly fiction in my head. No, not at all.

The Nature Drawings of Peter Karklins on display at the DePaul Art Museum through November 18.