Two Cabinet officials called for universities to follow U of C models and invest more resources to reforming urban health care and education, at a University-sponsored forum Thursday.

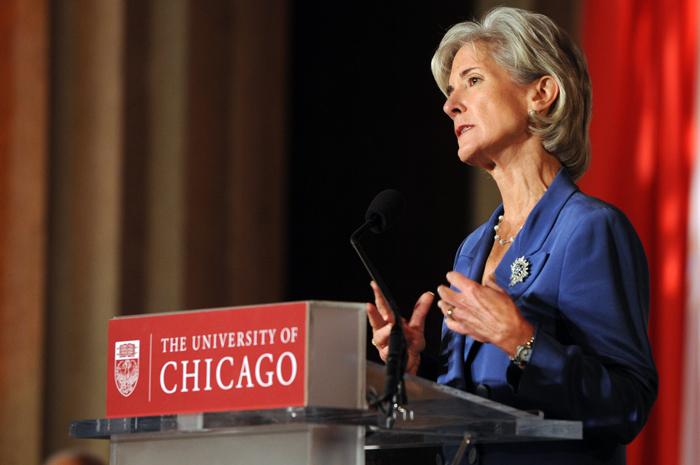

The Washington D.C. event, hosted by President Robert Zimmer, featured keynotes by Secretary of Health and Human Services Kathleen Sebelius and Secretary of Education Arne Duncan (LAB ’83).

Countering the stereotype that the University advances theory at the expense of practical knowledge, Duncan applauded the U of C’s role in education research.

“The fact is, you’re not an ivory tower in the middle of the city, but you’re running some of the best charter schools in the city, and arguably, the country,” Duncan said to a crowd of mostly University alumni. “You’re not just thinking theoretically about the problem, but you’re putting your resources on the line.

Sebelius, who started off the event, outlined many of President Obama’s concerns about the nation’s health care system, echoing his remarks the night before to a joint session of Congress. The country is facing rising health care costs, she said, but often receives only third-world care.

Sebelius moved past the upcoming legislative battle, and asked universities to focus their efforts on how the system can be realistically reformed once a bill is passed. “Then the real work begins,” she said. “And we want to tap your expertise as we change the way we deliver health care.”

A panel of five health care professionals, including Medical Center associate dean of community-based research Eric Whitaker (MD ’93), then discussed the problems with implementing that change.

The panel came back to community-based primary care models, like the University’s Urban Health Initiative (UHI), which directs Medical Center patients to local clinics and community hospitals to receive long-term primary care. While critics have claimed this turns away poorer patients, the panelists said plans like the UHI are what the health care system needs.

“We can put extra [beds] in medical centers,” said Kavita Patel, a White House policy director, “but we need to shift gears to a community-based model.”

All of the panelists agreed that advancing technologies aren’t any good against the basic problems many neighborhoods face, such as little to no fresh produce or public parks.

“We have to change…how we improve the health of the community, beyond building more clinics and hospitals,” Whitaker said, adding the University has invested in local farmer’s markets.

Whitaker also explained why universities shouldn’t strive to compete with public hospitals in providing primary care.

“Since 1986, six hospitals closed in Chicago because the University of Chicago out-competed them,” drawing too many patients to the University, he said.

The key for better health care, he said, is for high-tech hospitals to play to their strengths, while allowing community clinics to play to theirs.

“They do general care and we reserve ourselves for tertiary and quaternary care with a smattering of general care,” he said. “Not to make a Republican argument, but cooperation can be more powerful than competition.”

Duncan then gave the second keynote, recounting statistics showing the U.S. as one of the worst academically performing developed nations. He pushed for work like the U of C’s Urban Education Institute (UEI), which both runs K-12 charter schools and researches the impact of education policy.

“We need more of your willingness to roll up your sleeves, put your resources on the line, and invest in historically underserved communities.”

Another panel, this time of education experts, agreed that more universities should be more involved in improving education in the worst performing schools.

“The tradition has been for higher education to tinker around the edges of the hardest nuts,” Stanford education professor Linda Darling-Hammond said, “but fundamentally not have accountability for how the school performs in the long term. There are lots of escape hatches and they’ve been taken.”

UEI director Tim Knowles said the University has stressed the importance of a hands-on approach to education reform since John Dewey founded the Laboratory Schools in 1896.

“He taught the world that children learn by doing. If universities are to stay vital and not become obsolete in K-12 education, they need to learn by doing,” Knowles said. “We need to actually experience the difficulty of running a successful school.”