Editor’s note: The original stylization of the headline reads “West Virginia Chicago is happening to you. The fight for the modern university.” Having a strikethrough headline is not a design feature offered by SNO, but the headline should still be understood as having the strikethrough.

Last summer, the provost of the University of Chicago announced that, because “we are operating in a challenging fiscal environment,” her office would be imposing a variety of controls on spending in the current fiscal year (the email was sent on July 12, 2023; some of those controls were later withdrawn or revised). The announcement had an eerie familiarity. I have lived through financial crises at the University before. But I also understood that whatever I thought I knew, I did not have substantial and detailed knowledge of the nature or magnitude of the current crisis, or of its connection to earlier ones. This spurred me to investigate a set of intuitions I had long had, and that I have since learned was widely shared about the trajectory of the University as a whole and, indeed, many of its peers.

What I discovered, based on facts that the University itself provides, was that an institution that made itself look rich had also forced itself, in particular situations and for the purposes of specific policies, to act poor. The result of this imbricated set of choices, of overspending and underspending, has been the hollowing out of much of the arts and sciences at the University, with predictable consequences for the strength of its undergraduate College. But more is at issue than undergraduate instruction. At stake, I urge, is nothing less than the idea itself of the university.

What is needed in this moment, both locally and nationally, is clear-eyed analyses of the ideology driving these changes, of the culture of leadership and structures of governance that elevate these to institutional priorities, and of the mechanisms by which they are implemented and the costs they impose. In addition, we require a conversation about the gaps in oversight and public reporting that allow universities in particular to fail so often to live up to their own ideals.

________________

Some aspects of what is occurring may be described in terms that reveal the extent to which universities now participate in pathologies of leadership in contemporary politics and corporate governance. “Leadership” consists of “innovation”—meaning leveraged investments in new endeavors—and is measured by the willingness to take risks. Risk is most easily quantified in terms of debt. On July 1, 2006, the University of Chicago’s liabilities were $2.236 billion. By June 30, 2022, they amounted to $5.809 billion, meaning the University’s debt grew by 260 percent over this period and now amounts to a startling 68 percent of the University’s total assets. No, that’s not normal: no school in the Ivy League has a ratio of debt to assets higher than 30 percent. But it is “leadership”: in a recent letter to The Maroon, John Boyer, the former dean of the College, praised the “courage” of the University’s leadership in having “tak[en] formidable risks to achieve success.” It was presumably on the basis of a similar assessment that, over the course of this period, the base compensation of the University’s president grew by 285 percent. By comparison, a faculty member earning the standard merit raise each year would have seen an increase of around 60 percent in their salary.

To put the matter another way, in fiscal year (FY) 2006 the University reported cash paid for interest—the cost of servicing its debt—in the amount of $45.7 million. In 2021 and 2022, that number averaged $200 million. Neither is the totality of the University’s revenue available to pay these sums. Generally, it will have to come from tuition and assets without restrictions, not income from restricted gifts (which account for 86 percent of the University’s endowment, exclusive of the Medical Center and Marine Biological Laboratory), nor from grants. In consequence, in the fiscal year that ended on 30 June 2022, the University paid out $355.8 million more in cash than it took in.

To grasp the scale of the problem, for FY 2021, the University reported to the Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS) a net tuition revenue from each student of $31,500; as a result, the tuition of approximately 6,350 undergraduates, around 85 percent of the student body, is needed merely to service the University’s debt. What is more, some portion of the University’s debt was assumed after the 2007-2008 financial crisis, when interest rates were low. As these bonds come due—and principal payments totaling nearly $900 million are coming due over the next five years—the University will need to refinance at much higher rates. The same is naturally true of the new debt the University will have to assume to finance projects to which it has already committed, of which my own estimate with respect to the two largest building projects alone is $1.2 billion in additional borrowing.

What is striking about this situation is that UChicago is fundamentally rich, and yet its leadership—including, emphatically, its trustees, who must approve the issuing of bonds—seems to have elected to put itself in the situation of less well-resourced universities. The University has also not managed its finances well enough to escape the consequences of borrowing at this scale. On the contrary, as I have stressed, this year’s implosion is not UChicago’s first crisis in the modern era. Over the last decade, minor fluctuations in any one or more of several variables have produced repeated panics over liquidity, with the result that policy at every level and a great number of consequential day-to-day decisions are driven in those moments by a desperate need for cash. This was not necessary.

But University leadership—perhaps partly because universities are non-profit and their efficiencies are hard to assess—is rewarded even more than corporate titans for socializing the costs of their own risk-taking or, one might say, for inflicting harm on their own organizations. In FY 2016, as reported by Inside Higher Ed and Crain’s Chicago Business, the University reacted to a liquidity crisis by slashing the budgets of academic divisions by 8 percent, cutting large numbers of staff, and selling a large number of University buildings. Perversely, but also in reward, the president’s base compensation was increased from $1.056 to $1.090 million. (That these sales of University buildings were driven by short-term panic would seem to be confirmed by the fact that, in selling dormitories, the University gave up future revenue, just as its lack of liquidity has caused it in subsequent years to contract with external parties to build and manage new dormitories. Those contracts provide a lower return per person per room to the University than direct management of dormitories would have done.)

Compounding these factors are tendencies shared by universities with (poor) leadership in contemporary government, including a propensity to defer maintenance and kick costs to the next generation, and a penchant for encouraging boutique interests that are parasitic on public goods. The result overall has been a broad degradation in the ability of core units of the University to perform their basic functions.

But it is not sufficient to ascribe the actions of the University to a panic over finances, as though these were merely lamentable accidents. For one thing, the University’s leadership has repeatedly elected the same cluster of cost-saving measures in iterative crises, knowingly compounding harms that might at the first instance have been unforeseen. More seriously, the broad pattern of favor and disfavor in large-scale resource allocation reflects an ideological shift visible not simply at UChicago but across the nation, a revolution in the notion of the university from ideal to instrument and of knowledge from end to means.

Trustees and officers of the University are enabled to undertake this revolution, in what seems to me a tragic program of self-harm, by a general lack of transparency, and the reliance of the University at large on extraordinarily poor systems of public assessment.

________________

To grasp the nature and scale of the assault on the liberal arts at UChicago, we cannot focus solely on current events. Their story is simple enough. As noted above, in July 2023, responding to budget deficits (elective ones, of course), the University announced a range of constraints on research spending, a staff hiring freeze, and budget cuts nearly across the board. (I say “nearly” because I am told that the University has spent more than $3 million to renovate the president’s residence; this sum is greater than the aggregate research allowances of more than 250 faculty in the Divinity School and Division of the Humanities. To be fair, $3 million is not a meaningful amount for an institution with more than $4 billion in expenses; but in those terms, humanistic research is not meaningfully funded, either.)

But this year’s crisis is simply the latest in a sequence that stretches back at least 18 years. To understand properly the way in which the harms of this year’s cuts compound those of earlier years, it is essential to take the long view, so that the asymmetric effects of the cuts on units of the University are made clear. (The asymmetric effects of the cuts are, of course, in many respects the inverse of the asymmetric benefits that have flowed from the University’s leveraged investments.)

Apart from dormitories, the leveraged capital investments of the last 15 years have focused overwhelmingly on fields outside the historic divisions of the University (bracketing computer science), above all in areas of applied science, in molecular engineering in particular, as well as medicine.

Take, for example, the Marine Biological Laboratory (MBL). The University acquired the MBL on July 1, 2013. It was promised that this would not only bring massive benefits to research through synergies with the emergent Institute (later Pritzker School) of Molecular Engineering, but that it would have substantial pedagogical benefits at both the undergraduate and graduate level. The Council of the University Senate was also told that, after an initial investment by the University in renovations, cost reductions through shared management and enhanced fundraising would reduce the need for subsidies from the University to a negligible sum. The trend has, in fact, gone in the opposite direction. The University’s transfers to the MBL totaled $7.8 million in that first year; by 2016, the figure was $9.6 million; and in 2021, it was $13.9 million. I have been told by someone in a position to know that its Form 990 for 2022 will report a figure of $20 million. For what it’s worth, by my estimate, the figure for 2021 is already greater than the aggregated individual research accounts of all faculty engaged in interpretive scholarship in the Divinity School, Humanities Division, and Division of the Social Sciences combined—perhaps 330 people or more.

The Pritzker School of Molecular Engineering is, in academic terms, a remarkable success, and in a day-to-day way, UChicago Medicine generates enough income to subsidize the basic science departments of the Biological Sciences Division. But, as I have emphasized, the extraordinary scale of the University’s borrowing has repeatedly left it vulnerable to fiscal crises—of liquidity, of rising interest rates, of the downgrading of its bonds—that it has only been able to meet through programs of cost-cutting and at least one fire sale of University assets, which affect every branch of the University. For units that were not favored when times were flush, this has had devastating effects. Crucially, these harms are known to the University’s leadership, for it is on the basis of their own data that I discuss this problem.

________________

How shall we measure the effects of imposing multiple rounds of budget cuts on units that did not contribute to the crisis?

The Humanities Division at the University of Chicago spends just shy of 95 percent of its budget on salary and benefits. It is impossible to cut the budget, again and again, without cutting people—but since its budget, in a world of revenue-centered management, depends crucially on aggregate undergraduate enrollment, cutting people strikes at its ability to sustain and, indeed, justify itself down the line. So the Division has been doing more and more of its teaching not by means of “expensive” research faculty, but rather via instructional staff whose cost per course is much less and who are not required to perform research. The human costs and the challenges to the community of such moves are well known to everyone in the University; the costs are also epistemic, because the total coverage of areas of inquiry by research faculty is notably reduced.

The effects of this change are also visible in the College, whose own censuses of instruction—the so-called annual Johnson Reports—reveal that research faculty account for less and less of the instruction of undergraduates (from 2006 to 2020, the decline of undergraduate instruction by tenure-stream faculty was from 45 percent to 38 percent) while non-tenure-stream instructors account for more and more (over the same period, an increase from 22 percent to 38 percent). I am not claiming that the total number of tenure-stream faculty has not grown. Tenure-stream faculty in the Division of Humanities increased by something like 10 percent over that period. But the undergraduate population increased by nearly 50 percent over that time (from 4,703 to 7,011; it is now 7,540). That is the context in which an increase in the number of research faculty can nevertheless result in a greater percentage of instruction being performed by non-tenure-stream faculty.

The importance of this change can be judged by its relationship to University policy over the long haul. A major ambition of the College in the 1980s and beyond had been greater involvement of research faculty in undergraduate instruction, especially in UChicago’s Core Curriculum, and this was to a remarkable extent achieved. Needless to say, a massive increase in the size of the undergraduate population, absent a commensurate increase in tenure-stream faculty, was going to require the abandonment of this earlier policy and a recourse to non-research faculty for College instruction—the dismantling, in other words, of a great achievement of prior years. Does this accord with the promises we make to undergraduates? Is this in keeping with some of the highest tuition in the land?

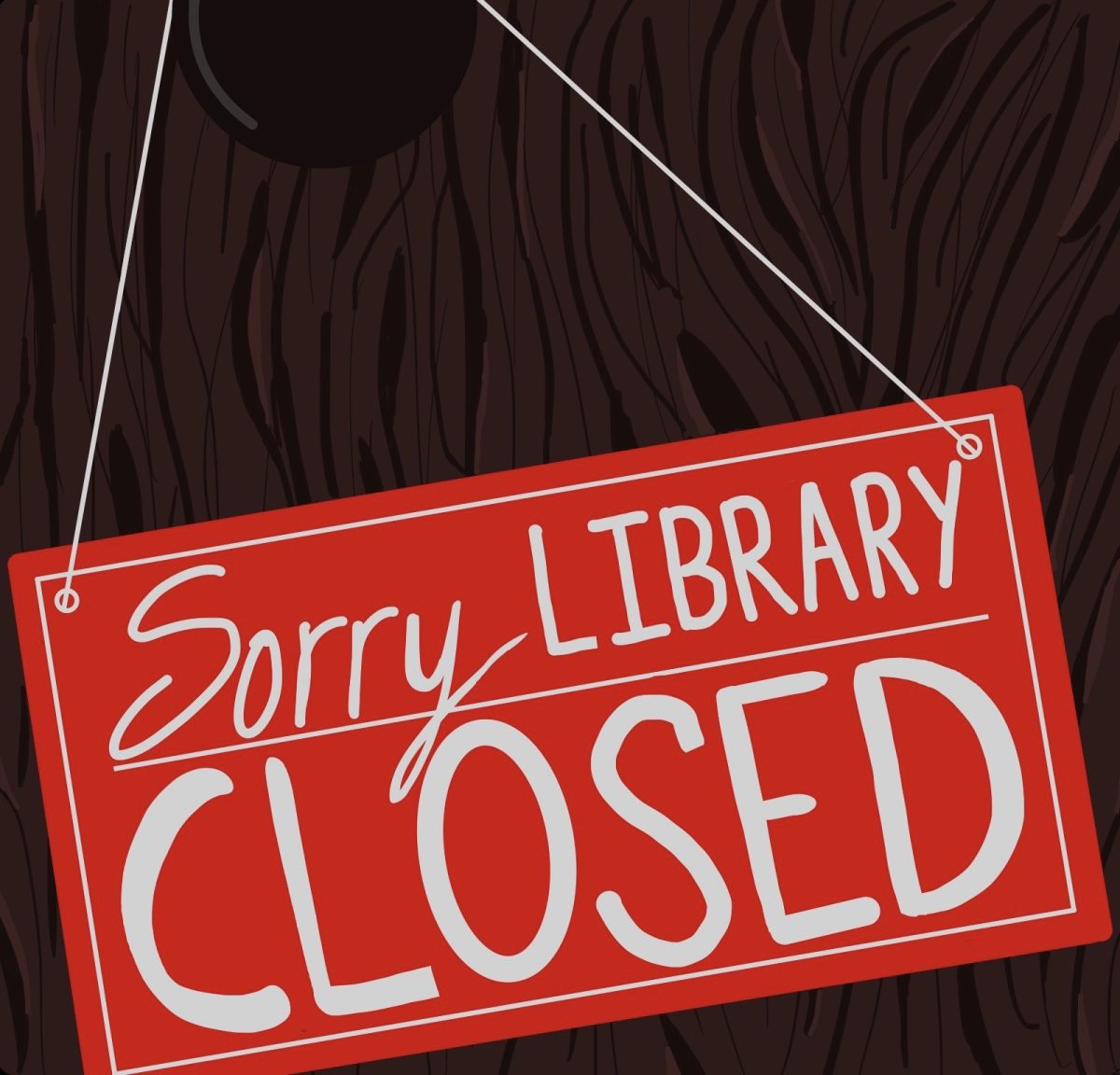

A similar dynamic is visible over at the library. The Association of Research Libraries offers rankings, according to self-reported data, of “library investment” overall but also more narrowly of “materials expenditures”: essentially, acquisitions, i.e., total spending on the products of culture and research that the library makes available for study and teaching. Using three-year averages to iron out year-to-year fluctuations, in 2006 the University of Chicago’s library ranked perhaps in the mid-teens of American universities in acquisition budget. By 2016, UChicago had fallen 10 places. In 2022, UChicago ranked around number 30. For a university that boasts a commitment to excellence in both pedagogy and scholarship, the library’s drop in rankings suggests, rather, a willingness to settle for mediocrity.

In short, the socializing of the costs of elective risk and targeted expenditure has struck at core functions of what one would have thought were essential units of the University. But to get the full measure of the transformation underway, and of the decline of support for the liberal arts, one needs to account for two additional factors: UChicago’s particular implementation of revenue-centered management, and the effects of deferred maintenance.

At UChicago, the implementation not quite 10 years ago of a system of revenue-centered management—allocating income from tuition according to aggregate undergraduate enrollment—immediately spurred many of the University’s professional schools to start offering undergraduate majors in business, public policy, and so forth. But these units do not contribute to the teaching of the general education curriculum (locally, “the Core”), which is required of the tenure-stream faculty in the Divisions of the Humanities and the Social Sciences, as well as the Physical Sciences Division. A result is that the teaching energies of faculty in the arts and sciences are more diffused because they must sustain this basic curriculum, even as the institutional homes of those boutique majors draw funds out of the arts and sciences.

Allocating revenue based on undergraduate enrollment does more than encourage a kind of parasitism on the labor that others devote to basic instruction. It also effects a kind of strategic ambiguation about the actual volume of revenue flows and cross-divisional subsidies. For one thing, the delivery of instruction has very different costs from field to field, so that no “formula” for the allocation of net tuition revenue could possibly account for costs in the same way from unit to unit. For another, in FY 2022, net tuition accounted for only 21.4 percent of the University’s revenue. In consequence, discrepant preferences on the part of leadership in the form of vast financial subsidies flow around the University and particularly to the physical sciences, entirely outside the visible and public logic of tuition allocation. This is perhaps the most essential policy issue lying wholly at the discretion of university leadership but with ramifications for every aspect of what we are and do.

The fact that the staggering majority of investment in buildings at the University has taken place outside the traditional arts and sciences (bracketing computer science and economics) only compounds this problem. A little over a decade ago, the University Architect informed a branch of the University Senate that the main university quadrangle faced $1.25 billion in deferred maintenance. This is precisely the order of magnitude of what the University is poised to spend on the Chicago Quantum Exchange and new Cancer Center, whose combined cost as announced is $1.415 billion (with $175 million pledged). It goes without saying that the quad houses most departments in the arts and sciences; the professional schools and new endeavors in the applied sciences exist in newer buildings outside this space. A further, related metric is supplied a census of faculty offices at the University in the period we might call “late Covid”: non-ventilated offices in which it was inadvisable to meet with students were, by an overwhelming majority, concentrated in the humanities, Divinity School, and the interpretive social sciences. I would expect a similar result if one were to survey the availability of ADA-compliant bathrooms, or windows that can open or, indeed, close.

To a startling degree, the University of Chicago has steadily moved to a regime of asymmetrical dignity and, indeed, asymmetrical public health in its basic conditions of work and learning.

This observation returns me to this year’s liquidity crisis and the budgetary issues of which it is an expression. IPEDS data suggest that the University has among the highest standard deviations in salary at rank in North America. For example, as best as I can tell, the annualized starting salary of assistant professors in the Booth School of Business is approximately 350 percent that of assistant professors in the humanities, a gap of nearly $250,000 (exclusive of research support, which would magnify the gap, and noting that junior faculty in Booth teach half the load of junior faculty in the humanities). More importantly, women earn less than men at every rank at UChicago: the gap is $21,000 at the assistant professor level and more than doubles—to $44,000—at the rank of full professor. This is known to University leadership. It is a feature and not a flaw of the current operation that the comfort of some is financed by the discomfort of the disfavored. But these gaps are elective, and we need not accept the claim that we pay some so little because of market forces or self-inflicted financial exigency, nor permit the austerity measures that will be necessary to address the current crisis to exacerbate these iniquities.

________________

All of this deserves public airing by insiders because these transformations and self-harms to core functions and core units of the University are extraordinarily difficult to perceive from the outside. The problems are essentially masked to important audiences, including, and perhaps especially, undergraduate applicants and their parents. In short, a lack of consensus on how to assess actual learning and instruction has resulted, where undergraduate instruction is concerned, in a system of ranking by parties external to the sector itself—most famously, US News & World Report—that relies more on inputs than outputs: selectivity of admissions, GPA of admitted students, and so on. This also means that our metrics for judging whether we are managing well the very difficult task of being a university are poor. In combination with the systems of governance and oversight that are present in American private universities, the outcome is little awareness, and virtually no means, to call ourselves to account if we fail.

Where UChicago is concerned, the situation should be analyzed on at least two planes. As a financial matter, the trustees have failed in their most basic function of guiding the University’s health qua corporation so that it is in a position to flourish as an academic enterprise. On the level of academics, the degradation of the Humanities and Social Science Divisions is short-sighted even on narrowly strategic grounds. Historically, they are the only units in the arts and sciences to score highly in international rankings. Treating one’s best and cheapest units as an ATM is an unforced error of such magnitude that it must be deliberate, the result of a fundamentally different view of what the University should be.

The goal at UChicago appears to be the transformation of the University into a gleaming network of professional schools with a disfavored and somewhat shabby teaching unit at its heart: the abandonment, in other words, of the idea of the research university that was current at its foundation and which UChicago itself did so much to cement in the national consciousness. That universities are moving in large numbers in the same dismal direction reflects the ideologically constrained worldviews that propel University leaders, presidents, and trustees alike, to the choices they are making. Financial difficulty is the context, and not the cause, of this transformation. We should dissent from this vision and this process.

________________

In closing, I want to insist that my ambition is not to take issue with any given discipline or endeavor, nor with the need to subsidize some units. I have no quarrel with an expansive view of what we should teach, and the fields in which we should work. But we have gone far down a road in which both research and teaching are assessed according to their susceptibility to be instrumentalized in pursuit of narrowly economic, possessive individualist ends. We have gone far down a road in which the only fields that matter are ones that are essentially isomorphic with particular occupations.

This is the ideological superstructure that is invited by the logic of tuition-allocation. It is the point where the principles that govern the University on the inside—in how we self-regulate—converge with the view propounded by politicians on the outside who want universities to cease their function of critique and instead train workers. It is the outcome of the application to universities of economic arguments that first gained ascendance under Ronald Reagan, in the dual and related endeavors to classify education as a merely private good and transform the funding of basic science into a means for private wealth creation.

That is foolish as a philosophy of pedagogy, and it is insane as a model of research. The silence of academic leadership on the idea and ideal of the University is incredible.

A note on sources

Both by way of making public the sources of my information, and to encourage others to undertake assessments of their own institutions, I offer here a note on the work that lies behind this article.

The leadership of UChicago has a pathology for secrecy. This article was made possible by two facts. First, a variety of financial documents of non-profits and issuers of bonds are required to be public. Second, the University seeks, to a notably high degree, to make high-level decisions based on data—data that it often does not make public and frequently does not share internally, even with persons who might do their jobs better if they had access to information that the institution already collects. I take these categories in turn.

For public data, I draw in particular on the University’s Form 990s, which are available in ProPublica’s Nonprofit Explorer. By relying on tax documents for all comparative claims, I seek to draw on data that all universities report according to the same standard. Universities are required to report compensation of “officers, directors, trustees, key employees, highest compensated employees” on those same forms; this is the source of my information on both base and gross compensation. Similarly, universities are required to identify “related tax-exempt organizations” and transactions with those organizations. The MBL is one such organization. But one needs to be careful. The data reported under this rubric is not remotely a guide to cross-subsidies within the institution since it only includes organizations with a particular legal relationship to the center. For example, some, but not all, of the University’s overseas centers appear in these tables.

Other financial information is drawn from the University’s Consolidated Financial Statements, which are issued late in the calendar year for the prior fiscal year. Figures for faculty salaries according to gender and net tuition revenue are drawn from the Department of Education’s IPEDS database, which, as I understand the matter, aggregates information that every institution that receives federal support of any kind must self-report. For claims about enrollment, I rely on the University Registrar’s website (which offers a summary graphic representation of the information) as well as the so-called “Census Reports” that the Registrar issues every quarter, which break down data along multiple axes.

In order to track the University’s large-scale capital projects, I examined multiple sources of information. I looked first to news releases on the University’s website. I also fed the address of every new construction and significant renovation known to me into both the Cook County Assessor’s database and the City of Chicago’s database of building permits. In some cases where, as far as I could tell, the University has announced only the sum it has raised and not the total cost of a given project, I have sometimes learned more from the websites of architectural firms, who are often keen to announce the scale of the projects they have under contract. But, in the end, I shied away from using and publicizing this information both because the public records sometimes make ownership hard to determine and because it seemed to me likely that the multiple figures from different sources were constructed according to different standards and priorities, and this rendered aggregation difficult.

Regarding data that the University gathers and analyzes but does not make public, the University as a whole undertook a quintile analysis of salaries across the disciplines more than a decade ago, and the exercise was repeated in the Division of the Social Sciences in 2014. Every year the College produces a statistical study of instruction called the Johnson Report; it includes annual data regarding things such as per capita instruction of undergraduates by department and division; it also includes charts that track, over periods of 10 years or longer, numbers such as undergraduate courses taught by different classes of instructor.

Clifford Ando is the David B. and Clara E. Stern Distinguished Service Professor in the Departments of Classics and History and in the College.

CMS / Jan 22, 2024 at 12:24 pm

Just for additional context and to open up some secrecy, 30% of Booth Marketing staff were laid off earlier in January 2024. The Dean said it would be better for collaboration and not financially motivated… Many staff workers were laid off or furloughed in the early pandemic. Their spots not refilled. These efforts always disproportionately affect women and minority staff.

Scott Gurvey / Jan 21, 2024 at 10:56 am

What’s with the nice picture that doesn’t show the University?

M. Hedy / Jan 19, 2024 at 11:57 am

Even though he’s in Classics and History, Ando should do math correctly. Liabilities going from $2.236B to $5.809B represents an increase of 160 percent, not 260 percent.

MM / Jan 15, 2024 at 11:05 pm

Brilliant article—thanks so much for this analysis!

Kindred Spirit / Jan 15, 2024 at 3:01 pm

When the university responds to this, the pathology of secrecy will no doubt deepen. They will say that the analysis is flawed because it relies on incomplete publicly available data that is inferior to internal data. Of course, the “better” internal data cannot be released, so you will have to take their word for it.

Michael O'Donnell / Jan 14, 2024 at 5:07 pm

I am puzzled by the phrases, “bracketing computer science,” and later, “bracketing computer science and economics,” and would like to know what they mean.

David / Jan 19, 2024 at 3:10 pm

It means excluding/excepting those schools which otherwise would have been included in that grouping.

Clifford Ando / Jan 24, 2024 at 3:43 pm

Exactly; thank you. The point being that those two units received (and receive) investments from the center wholly out of proportion to the revenue that otherwise flows to their Divisions. My point is mathematical rather than normative.

Jacob Myrene / Jan 14, 2024 at 4:37 pm

Ando has flooded The Maroon with his catastrophist rhetoric for three months now. At first, I was sympathetic to his views. However, I have since become skeptical. The irony of exposing the University’s dire financial state while simultaneously whining about budget cuts to non-STEM programs is clearly lost on him. Ando knows full well the humanities programs strain the University’s finances immensely, and likewise that the University would do well to INCREASE funding cuts to and reinvest those savings in lucrative STEM fields.

Clearly, Ando’s judgment is muddled; he is biased towards his own, selfish interests (i.e., retaining his overpaid position as a professor of a money pit) rather than those of the University. Shameful. I call on The Maroon to prohibit further contributions from him on this topic. Get someone from Booth to weigh in, or, better yet, interview someone from the administration—anyone who isn’t sympathetic to Ando and his pro-humanities AGENDA.

Moreover, neither Ando nor the resident dinosaurs of The Maroon’s website comments seem to appreciate that the direness of our financial position necessitates radical changes. These people have been so indoctrinated by “Life of DUH Mind” propaganda that they can no longer reason objectively, and would rather venerate this place’s ANITQUATED, FOOLISH, and MEANINGLESS customs than propose serious solutions.

Allow me to help:

1. Do away with the CIV and SOSC requirements (perhaps make them optional?). Terminate associated faculty forthwith.

2. Eliminate nonsense majors/minors, that is, majors/minors that fail to attract a meaningful proportion of students. Music, Art History, Classical Studies, Education and Society, Gender Studies, MAAD, Jewish Studies, Medieval Studies, Yiddish Studies, Music, Religious Studies, etc. all need to go. NOW. Useless majors that give graduates no prospects.

3. As I wrote in a previous comment, humanities-centric buildings need to be gutted and turned into technology and science labs.

4. More STEM majors that will produce exploitable alumni. Mechanical engineering, electrical engineering, etc. See UC Berkeley’s EECS program for an idea of the curriculum we ought to strive towards.

All this talk by commenters of “donations, donations, donations” from alumni. Poor people can’t afford to give, folks. And the fact is that most of UChicago’s alumni are comparatively poorer than those of “peer” institutions because this place indoctrinates its students to value meaningless pursuits.

Reform. NOW. MORE Harvardification, not less. Do away with these quirky barriers to entry (e.g., the uncommon essay). EXPAND the business economics program. Recruit WEALTHIER students; do away with the Odyssey program and other free rides. For goodness’ sake, we have been surpassed by Northwestern by most metrics!

It’s time to grow up. No one cares for our culture of uppity intellectualism. NO ONE. Until the DINOSAURS of UChicago’s past get off their high horses, we will continue to spiral.

David / Jan 19, 2024 at 3:13 pm

You had me for a few sentences

Clifford Ando / Jan 24, 2024 at 3:49 pm

I’m not entirely sure what to make of this comment. It commences with a factual error. I wrote something for the Maroon on December 21, 2023, and again on January 14, 2024. That’s not three months, and doesn’t appear to me to qualify as “flooding.”

Also, I don’t “know full well” that humanities programs strain the university’s finances immensely. The Division of the Humanities is not expensive and its deficit last year was comparatively tiny. Relying on the form of accounting I have seen, the Humanities Division as a whole contribute less than 0.5% to the University’s deficit.

I could say more about what standard internal forms of accounting at universities do and do not reveal, but much of what follows by way of suggestions and argument in this comment need to revised in light of this quite fundamental error about its premise.

Matthew G. Andersson, '96, Booth MBA / Jan 14, 2024 at 1:41 pm

Mr. Ando makes some important assertions, and it is noteworthy to see a department head exercise critical thinking at an institutional level, in a public forum. He is to be commended. May I offer a few observations, as an alumnus, and as someone involved formally with a number of higher (and secondary) education programs and assessments. It is natural for the writer to effectively lobby for his own interests as a department faculty member in a division that is especially challenging to sustain financially. He does however, put his finger, perhaps unwittingly, on one of the sources of financial relief when he states, “The Humanities Division at the University of Chicago spends just shy of 95 percent of its budget on salary and benefits. It is impossible to cut the budget, again and again, without cutting people.” Quite so (it is curious, of course, why the all-faculty budget apparently so consumes deeper student scholarship resources, and inflates tuition pricing). But unfortunately, all corporations–and universities are corporations–must make such adjustments, often because of over-hiring. For example, the number of related Chicago faculty and staff, outnumber College students. The next thing Mr. Ando might do, is publicly stand up his department financials, as a business unit; justify its economics on a present value basis, and suggest ways to structurally improve. Every department–and professional school–can do the same (and does typically, internally as a report, although not usually for restructuring). The candid financial posture Mr. Ando seeks otherwise, best starts from the “bottom-up.” Moreover the entire concept of “departments” naturally leads to bias escalation not only in ideology, but in economics. The bottom line is that UChicago is not by any means alone in facing a key economic opportunity: everything it does can be done better, for half the cost, by removing or reducing waste. This includes time-to-degree, which in the US, is up to 3x longer and more expensive than in the UK, most of the EU, Latin America, and parts of Asia. Waste reduction and fixed and variable cost improvement naturally lead to difficult choices (but unexpected improvements) including to what extent, or whether, universities need senior administrators in employment roles. In the private sector, the first institutional adjustment is usually in leadership (and finding effective leaders is not easy, especially if the academy seeks to maintain undue influence, where all costs must be “put on trial”). Readers may enjoy an opinion I wrote for the Financial Times that briefly outlines this opportunity, “Overhaul Likely to Mean Business as Usual at the University of Chicago.”

James Vice, College x'52, Soc AM '54 / Jan 20, 2024 at 10:15 am

“Stand up his department as a business unit” says it all. Perhaps these business units should be established as a separate institution. (I vaguely remember that the business school was a later addition to the Univerity.) The University was established as dependent on charitable givers with a classics department and oriental languages and literatures (and geography and I think some others that disappeared in budget cuts). Harper’s field was Semitic languages—certainly not a money maker and WRH was dependent on Rockefeller (not an alumnus). I doubt Frank Knight (co-founder of the “first Chicago School” of economics) ever brought in money, and I have long noted with great regret that there is no endowed professorship in his name. Perhaps MAG might work on that. Knight was a dominant figure in the Social Sciences in the middle third of the last century and would almost certainly had a Nobel in economics had he lived long enough. (Richard McKeon also deserves an endowed professorship. At least he now has a research center.)

William Sterner AB '69, MBA '82, Ph. D 2018 / Feb 26, 2024 at 10:26 am

Great to hear your reasoned voice again, Dean Vice, as it brings institutional history and goals back into view. I completely support your professorship proposals as valid budget projects. Sadly, high income employment after college has become the highest purpose in going to college, as I’ve witnessed in students over decades of involvement with the University. Deep critical thinking is more needed now than ever, and yet most of these “profitable” majors have little or no critical awareness of their own cultural deficiencies, much wider social cultural problems. Hitchcock ’66 & ’67

Jack Honig / Jan 25, 2024 at 6:46 pm

This is completely right, in my opinion. The simple facts are that the humanities simply don’t provide a financial return to students. That’s fine if you come in without any debt, but most students have to take on at least some portion to be able to attend. Humanities doesn’t pay enough to make that equation worth it for the vast majority of students and as such enrollment falls. The less students, the less income coming into the humanities department, and thus the more layoffs and cuts that are made. Professor Ando is missing the forest for the trees: the problem facing the humanities isn’t that UChicago is deprioritizing them as opposed to the STEM fields (although I agree that such a turn is certainly happening), but that the humanities can’t justify its own existence with the price of education being what it is. Fewer and fewer students are coming into the humanities, and without a meaningful change in the job market, that trend will only continue. Without creating new jobs for humanities students (and not just within the academic ivory tower) or cutting costs by switching to a more European model of university, nothing will change.