In his last published work, Maurice Sendak convincingly showcases both the old and the new. My Brother’s Book is a culmination of the artistic breadth cultivated over the span of his long and successful career. It is, at the same time, an ode to his beloved departed brother Jack and to many other people he has lost. His verse is classic with a hint of the absurd: a relatable fairytale, a sad human search through a phantasmal land. It is in his artwork—a range of images that are sometimes impressionistic, sometimes gothic, sometimes something else entirely—that the full potency of this creativity is revealed. And with it, one of those rare pieces for readers of any age.

Sendak’s work is said to have been inspired by Shakespeare’s A Winter’s Tale, and elements adopted from the play are evident throughout: the “bleak midwinter’s night” upon which the story begins, the descent into Bohemia, the menacing Bear reminiscent of Ursa Major. But My Brother’s Book is much more than an adaptation. It verges on a prophecy of its own.

A deceptively simple theme—the eternal need for love—is tastefully executed, but could seem, at first, a bit cryptic. Brothers Guy and Jack are apocalyptically separated as the Earth itself is cleaved in two by a crashing sun. Guy is thrown back into the starry rays of the Universe under the euphoric gaze of the light; his brother is left astray, eyes covered in sheer horror, not at the end of the world, but at the torment of seeing his other half taken away. For such is the depth of love, one comes to understand. Through this allegory, the portrayal of the utter real-life despondency that comes with lost love is nothing if not palpable.

It is Guy’s subsequent search for Jack through many realms and “soft Bohemia” that is so very endearing. His is a reflection of the myriad “lost” dispositions in which we find ourselves when embarking on the search for love. Along the way, we, like Guy, fall into the many unknown worlds of which life is composed. “Diving through time so vast—sweeping past paradise/…/Guy listened to the meadow bird’s solemn song,” writes Sendak. It is, perhaps, the universality of this image that is so striking, the unanimous understanding that, difficult as it could prove to be, anyone would cross worlds for a brother or a friend. It is here, at the apex of Guy’s journey, that Sendak’s poetry is at its most powerful—a subtle mix of beauty and simplicity reminiscent of something written long ago.

Adult though this may seem, the very childlike elements that distinguish and inform Sendak’s work are by no means missing. At one point, Jack is flung into the ice and frozen for five years, along with his nose—a veritable Jack Frost. Sendak’s cunning employment of the ubiquitous Bear is equally silly. The book’s lack of unanimous symbolism works to its advantage, for it raises a slew of unanswerable but tantalizing questions. Does the Bear represent the obstacles one must face to arrive at, to achieve, to retrieve what has been lost? Or does this Bear who “hugged Guy tight/To kill his breath/and eat him—bite by bite” demonstrate the agony of life’s journey, at times an inner torment that brings the breath to a stuttering halt as would asphyxia by Bear? Luckily this potentially life-threatening creature is just a humorously impatient (and hungry) Bear who just doesn’t want to listen to Guy’s riddle.

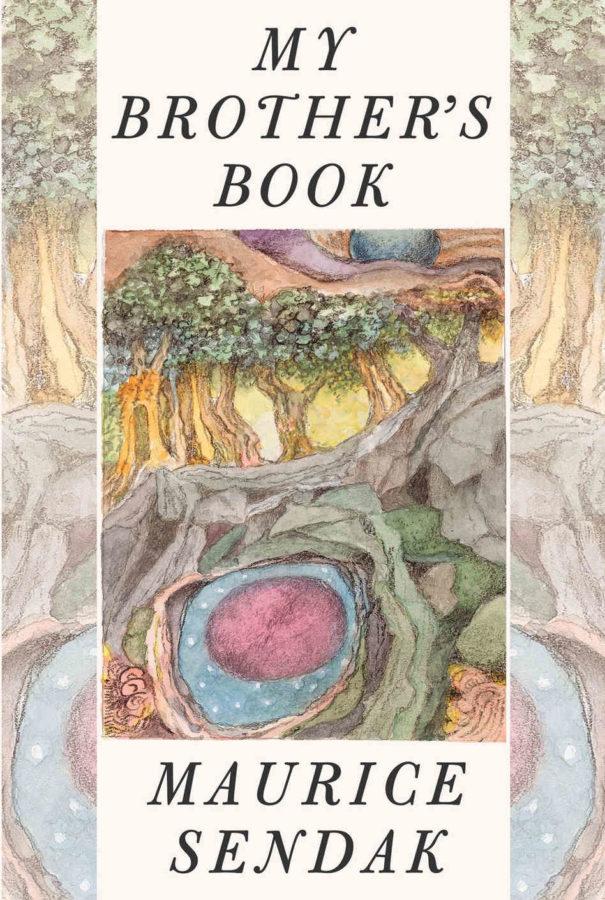

The variability inherent in his imagery is, therefore, all the more noted. His artwork employs a striking mélange of colors discernible by the depth of their vibrancy: deep yellow hues and varied greens, shaky blues, and hints of the rainbow as one would imagine them reflected on a pearl. The constant backdrop of the Universe only adds to the piece’s elusiveness, as if to imply that it is the sort of rendition the scope of which could only be captured in space.

These features are offset by a cohesive, yet absurd, style that does not shock, but does not entirely soothe. The animation in the brothers’ despondent faces and the cruelty of the Bear’s snarl reflect the depth of Sendak’s grief. It is an eerie thing to witness the airy, pallid luminosity of a frozen Jack intertwined with jade trees. Each image is, indeed, marked by the presence of nature. The progression to its more colorful rendition (Guy finally meets Jack near the pink cherry blossom trees) is wonderfully symbolic of the change in perception that occurs when in the vicinity of those one loves: Reality is a kaleidoscope as “Guy sat upon a couch of flowers in an ice-ribbed underworld,” finally reunited with his long-lost brother.

My Brother’s Book is touching without being sentimental, concise yet memorable. For the avid reader of poetry, the fan of children’s tales, and the ponderer of the traits that unite us all, it is a must-read. More than once, for good measure.