Kanye West is broken again, fitful, a little disorganized. It’s been five years since he released the stunning 808s & Heartbreak, and three since his Armageddon, My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy. Since then he has paired up with his mentor Jay-Z for a brilliant collaboration album, delivered a clothing line at Paris fashion week, and become a father with a reality TV star. It’d be hard to think that West hasn’t had the encroaching fear that his musical genius isn’t enough, that the demands of his emotional insecurities and commercial enterprises must supersede his pleasures as a rapper and producer. His cultural preoccupations have become antidotes to his artistic ingenuity. There are new spaces to consider, a bigger legacy at stake. But as his entrepreneurial aspirations have become less coherent, his music tastes have become sharper and more insistent. Yeezus, his most recent album, is one of the best of 2013, a prototype of musical attraction-by-repulsion.

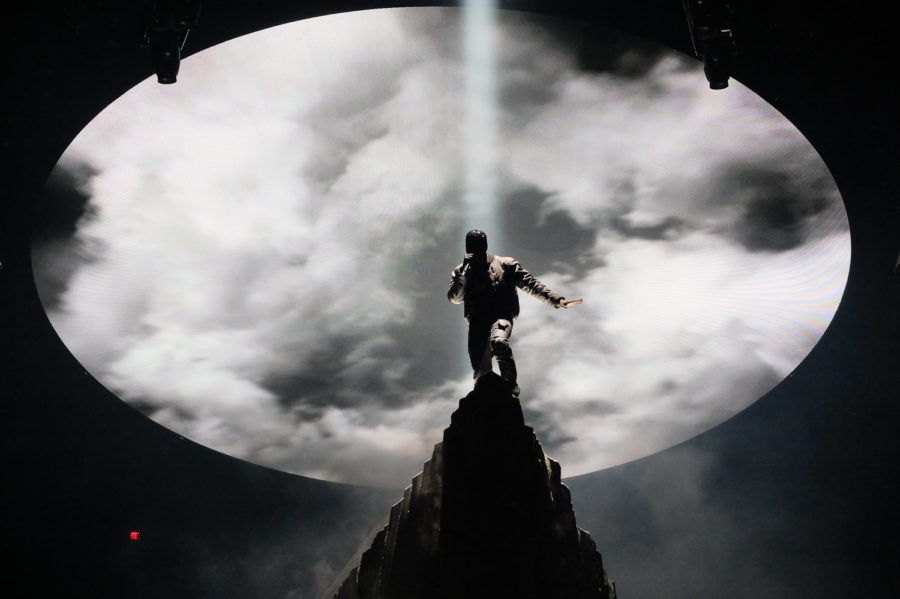

Ten days ago West performed at Madison Square Garden in New York City to promote the album, and by extension his new life. Over a two-and-a-half hour set, he proved once again how unparalleled his live performances are: there are few pop artists as ornate and detail-oriented in arena shows, and few more intent on pleasing the audience, either by sound or visuals. He runs, preens, dances, lurches, struts, and lies down. He shouts into a microphone, screams into a vocoder, pleads into an autotune device. He climbs a holy mountain on stage, stands atop a mock cliff in the middle of the arena, and kneels before a man dressed as Jesus. Considering Kanye’s propensity for honest self-deification, there may be less irony in all this than there should be.

But the music in the show comes through just as it should. He designed a set and a set list suited perfectly to Yeezus, which he performed in its entirety. The show was organized into five thematic sections, arranged with parts of his discography that fit the “Fighting,” “Rising,” “Falling,” “Searching,” and “Finding” headings announced before each entrance. For each part, Kanye wore a new mask, usually covered in diamonds. Not until the intimate encounter with the Jesus look-alike (no really; it was touching) near the end of the show did he finally show his face—too late for anyone to have believed he had a body double perform flawlessly for two hours.

This is the first Kanye show I’ve seen for which he so masterfully organized his music into themes and moods, relating the different sounds he’s toggled with over the years. Part of the challenge for Kanye now is figuring out how to commemorate his past music and self: as he becomes more aggressive with his newfound artistic proclamations, there’s naturally a break between his current identity and his past self—one that could sap some of the original energy from older, and perhaps more modest, records. Rarely did there seem to be any kind of self-abnegating. His performances of “Jesus Walks,” “Diamonds From Sierra Leone,” and “Through the Wire” were effective self-tributes, if not genuine reinventions of his past.

The songs off Yeezus were performed confidently and with little surprise. Some of the more underrated songs on the album like “Guilt Trip” didn’t garner as much interest as the better-known hits. The most distinctive connections between his discography occurred in songs from 808s and Dark Twisted Fantasy, which come from the same fraught, cathartic space, and were delivered with the fervor and brokenness that comes through on the albums. If anything, his recent songs have become more pronounced and muscular, stripped of the effortless flow that defined his early music. Songs like “Runaway” and “Heartless” were devoid of any drama, replaced by some of the stark vexation that oozes from Yeezus. On the songs that did require the gloom of 808s, he was suitably despondent. He sang “Coldest Winter” on his back with fake snow falling from the ceiling.

It’d be a mistake to think that his older, more flexible, and more lyrical music, is better than his recent, more industrial material. The best pairing of the night was “Cold” with “I Don’t Like,” his remix of Chief Keef’s Chicago drill rap anthem. For “Cold,” West reemerged on stage to merge M.O.P.’s “Cold as Ice” intro with his own eponymous version, making for one of the coolest entrances I’ve ever seen. The performance of “I Don’t Like” was the most abrasive track of the night, the audience eager to plunge into Young Chop’s prodigious bass thumps. As Kanye has adopted a more pungent sound, he has attached himself to some of Chicago’s most ruthless voices. Chief Keef and King Louie, two of Chicago’s most visible young drill rap practitioners, worked with Kanye on Yeezus, and he was proud to display their influence at the show.

Regrettably, the takeaway for most fans of this tour will not be the music; it’ll be Kanye’s antics, on full display throughout the night. The new Kanye, assuming there is one, is more interested in people recognizing the profundity of his ideas outside the music world. He thinks there are serious problems: that people aren’t fully recognizing his potential as a clothing designer; they’re “marginalizing” him, as he often pointed out. At several points throughout the night, he complained that his fans are eager for more hits, but not for his next pair of shoes. To stoop even lower, he groused that corporate executives want more hit songs that raise his profile, or for Kanye to perform at their kids’ Bar and Bat Mitzvahs, but not to help him achieve his other dreams.

He whined, for upwards of 20 minutes, that Lenny Kravitz’s commercial projects in Paris were self-limiting, that big fashion designers don’t take him seriously enough because they now preclude the possibility of Kanye being a world historical figure worthy of his own clothing line. In a series of wildly incoherent and temper-ridden radio interviews from the past few months, Kanye has tried to establish the reasons behind his frustration, only to give his fans, and his skeptics, more material to mock him for. He believes the cultural or mogul status of Jay-Z, and of technology luminaries that Kanye professes to worship, like Steve Jobs, trumps the significance of his musical genius. Yet he continually fails to recognize that the quality and influence of his music is doing, and will do, the requisite work to establish him as the kind of cultural figure he’s still trying to be, albeit not the divine figure he thinks he already is. That the right people aren’t giving him the right chances right now doesn’t mean that he isn’t being given a chance.

There was a point near the end of one of Kanye’s rants at which the audience was audibly anxious, unsure of how to square the fun Kanye with the doctrinaire one. It feels safe to assume there’ll be a time in the next decade when Kanye fans don’t want to put up with this anymore, when the music will still be alluring but the messenger too antagonizing. Because West seems so intent on proving something, on showing you that he is right about something you simply don’t understand, only weakens his case. He makes it harder for his most committed followers to keep reconciling the different junctures of his professional and personal lives. It shouldn’t be this challenging to sympathize with someone so smart and gregarious.

Kanye’s fear that something is holding him back just isn’t as deep as he wants it to be. Not getting the chance to participate in strategy sessions at the Versace headquarters doesn’t elicit much pity from the people who are supposed to grasp the broader social and political points Kanye is ostensibly making. His obsession with his art and clothing as anti-establishment, anti-corporate resources proves exactly the opposite: that clothing and fashion can be the easiest, and fastest, ways to accumulate the kind of cultural capital he wants, and that they’re as corporate as the business executives he regularly derides. If he wants to scapegoat the corporations that won’t materialize his artistic concepts, he can’t then plead for their acceptance at the end of the show, as he did in New York. He begged—by name—almost a dozen American corporations to believe in him and his dreams, lest the CEO of American Express (who was in the crowd that night, as Kanye noted) see the Yeezus Tour and not think Kanye is the ideal brand ambassador. Any reasonable thought he has as an entrepreneur gets clouded by his brazen self-contradiction.

Kanye, perhaps to compensate for the elitism of his aspirations, was intent on empowering the audience. Near the end of his main rant, he forgot to ask us to raise our hands if we believe we can do anything in life (apparently a Yeezus Tour trope), so he rushed out on stage to demand this, then quickly walked off, as if the act was ironic in the first place. His dreams (thwarted yet again) of designing clothes for YSL are, implicitly, the kind of dreams all of us can and should have, even though Kanye announces that anything he touches is superhuman—better than anything any mere mortal could conceive of, or even understand. This is a kind of empowerment, object-obsessed at its core, that only encourages an unhealthy disdain for anything and anyone ordinary.

During his performance of “Blood on the Leaves,” the closest thing to an opus on Yeezus, the smoke machine operator got a little zealous, and Kanye was the first to notice. After the song ended, he castigated his tech crew, pointing out that all the smoke was preventing the audience from taking clear Instagram photos. “No new ideas without me,” he shouted. That moment might as well be the symbol of everything wrong, and right, with Kanye. Soon after, he jumped rather ambivalently into “Stronger,” one of his most athletic songs. The rendition this time was moodier and more deliberate, punctuated by a beautiful laser-light display rotating around West. There was no joy in this performance, no finesse. But maybe that’s how it should be. There was more feeling in the song this time, however conflicted it may have been. There are other things on Kanye’s mind, and if it’s too hard to reconcile the genius of his music with the messiness of the other parts of his public life, that doesn’t mean we should turn away altogether.