Jerome Rothenberg performed samples of his poetry on Thursday evening at the Logan Center. The performance was the final installment of this year’s Reva Logan Poetry Series, curated by Srikanth Reddy of the English department, a tradition that began with the opening of the building in the fall of 2012.

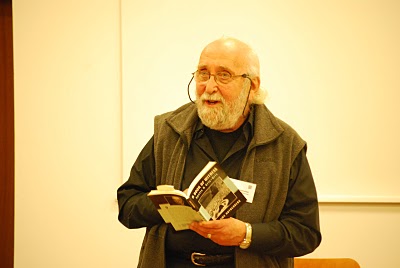

Reddy opened the event with warm words of praise for Rothenberg, reading the intriguing conclusion of the visiting poet’s “The Chicago Poem” during his introduction. When Reddy stepped away, a short man with long white hair knotted behind his head walked to the podium in a black T-shirt and suit jacket. Picking up his own thick book of poetry, Eye of Witness, an anthology collected from his 80-plus books of poetry published in 2013, he laughed. “I’ve never thought of myself as a prolific writer…but over 50 years, it accumulates!”

The unexpectedly inventive and humorous poet began with the complete version of the same poem with which he had been introduced, but to say that it sounded different would not be enough. He spoke in a lyrical, gruff, and joyful voice. The words flowed out of him and were one with him.

His commitment to truly performing his pieces makes sense. Over the course of his career, he pioneered a field known as ethnopoetics, which seeks to transcribe words passed down through oral tradition in a format that captures much of the original presentation. As the poetry reading progressed, he shared several pieces he called “songs without words” that involved Native American instruments, singing, and–in one instance–a string of strange but distinctly human noises. He claims many things as poetry, and in the way he brings them to life, that naming seems apt.

Given his prolific career, Rothenberg’s work crosses a wide span of time, but it also crosses many areas of genre, topic, form, and content. When the content was inaccessible, whether through his constant detailed references or the presentation of seemingly unrelated images, he still made it enjoyable. Yet he also performed a small but significant number of deeply moving, profound works, such as a lengthy poem about human mortality and the approaching conclusion of life for his friend, his wife, and himself.

Rothernberg’s reading was a fitting conclusion to a series featuring influential modern-day poets of all different sorts. Having worked for over 50 years writing, translating, and editing poetry and many other unique writing formats, he is experienced and knowledgeable. Even at the age of 80, he remains knee-deep in the field, continuing what seems to be his natural inclination to always move forward and explore.

In his accompanying talk last Friday, he spoke candidly about poetry and his work. He discussed the process of re-engaging with one’s own prior work, something he did extensively in putting together the recent anthology of his life’s work. Even as he read his poems, he would sometimes laugh to himself. After performing one older piece written during his time on a Native American reservation in New York, he paused for a minute and remarked, “It’s strange reading these after all this time.” Even a man of such wide and varied interaction with poetry can be surprised by his own words from time to time.