As far as protests go, until someone starts throwing Molotov cocktails, the footage isn’t likely to make international news. When the Egyptian revolution kicked off with mass-organized protests in Tahrir Square, deadly clashes broke out all over the country with protestors and police squads exchanging deadly volleys of tear gas, rocks, and rubber bullets while the world watched with baited breath to see if a social media–fueled revolution could topple yet another Middle East dictator with the glorious forces of democracy. In China, after Beijing broke its promise of free elections by declaring veto power over the nomination process and 800,000 people in Hong Kong signed a protesting petition, hundreds of thousands of demonstrators have marched through the streets demanding the right to self-rule. And yet the recent protests in Hong Kong have received no such attention. Perhaps the struggle for free elections isn’t that interesting after all—we just want to sit back and hope to see a big brawl. Although Hong Kong is technically part of China, the 155-year-British colony has taken on a more westernized identity, complete with a free press and a general assumption of sovereignty. This expectation of freedom is now on display from the government headquarters to the tourist districts of Mong Kok and Causeway Bay in an unprecedented display of public disobedience.

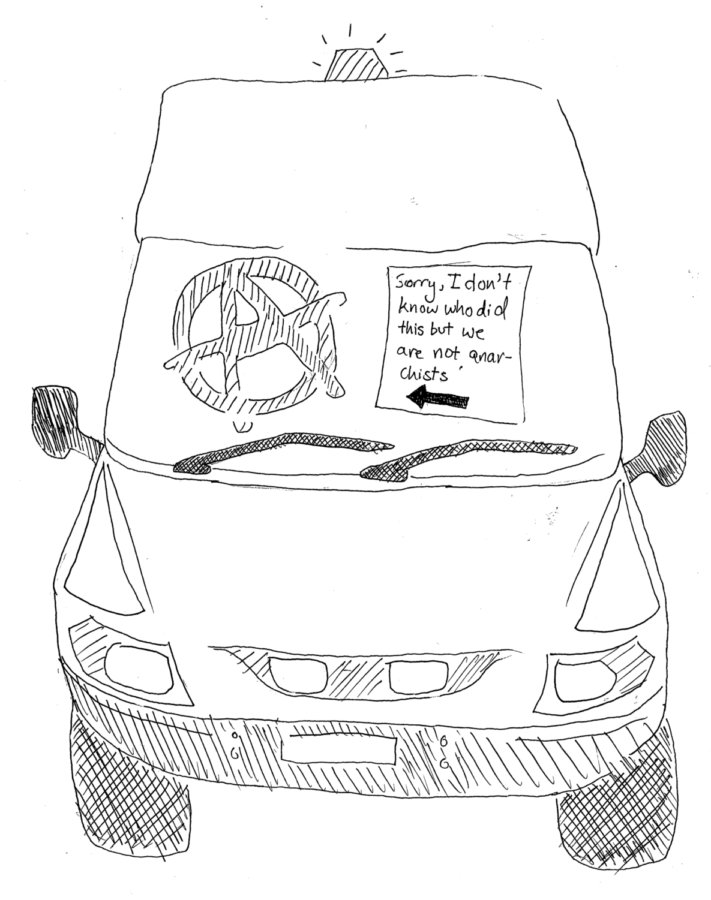

Not since Mahatma Gandhi have we seen protests of such scope and peacefulness. The very symbol of the Occupy movement of Hong Kong has become the umbrella, the defensive tool of choice in response to police use of tear gas. In contrast with, for example, the Occupy Wall Street movement, the activists in Hong Kong have a singular clear demand and the intent to continue however long it takes to build up sufficient political pressure for mainland Beijing to capitulate. After every night of contentious protests, students spend the morning cleaning up the streets, handing out water bottles, pitching tents, and putting up posters. One pro-democracy supporter tweeted that Hong Kong was “a city where protestors don’t smash up shops, and they also clean up after themselves, yet get teargassed and pushed by the police.”

But despite the obvious popular support for free elections, Beijing has chosen to dig in rather than give way. Actively blocking all television footage of the protests and declaring through Hong Kong’s Beijing-backed leader (who has been asked to resign by the Occupy movement) that the protests have “almost zero” chance of securing an election process over which Beijing does not have ultimate control, the Chinese Communist Party has made it abundantly clear that progress is not just beyond the horizon. In the face of such intransigence, the lack of escalation on the part of the protestors is truly remarkable.

On its face, the conflict seems clear cut. Hong Kong wants the power of self-determination, and Beijing just wants power over Hong Kong—the essence of democracy versus imperialism. The public stances of western democratic powers on the Occupy movement reflect just that, with the U.S. issuing a statement saying that it “supports universal suffrage in Hong Kong,” defined as “a genuine choice of candidates representative of the voter’s will,” and the U.K. similarly declaring it “essential that the people of Hong Kong have a genuine choice of chief executive…through universal suffrage.” From a political perspective, the former British colony is still fairly moderate in its views toward the mainland—the people of Hong Kong care about free elections in principle, not because the leaders they wish to elect are fundamentally intolerable to Beijing.

But the Chinese Communist Party isn’t trying to control Hong Kong, not really. With mainland China’s economy on the rise, Hong Kong is no longer the economic backbone of the nation. Instead, it’s afraid that if the protests are successful it will set a dangerous precedent that the police state of China would not survive. Why else would any media coverage of the situation be so heavily censored? Forced to accept free markets to become an economic superpower, the ruling party still clings to the notion that democracy is not similarly a requirement for prosperity, so through propaganda and repression they maintain the illusion that for China there can be no alternative. If Hong Kong, a different government but part of the same China, were to suddenly become a stark counterexample, the people would realize that they have some hope for realizing change through non-violent political action. China could likely quell any sort of armed rebellion, but such a social awakening would be nearly impossible to control.

All context aside, the point is Beijing said “No,” and that’s looking like the end of it. When 846 Egyptians died in their revolution and over 3,000 people were injured, the world paid attention because even though the politics were complicated, whatever the protestors wanted was worth dying for. But people shouldn’t have to pay for their freedoms with their lives for us to care about their oppression. And if we don’t care, who will? After talking to several Chinese students, it became apparent that the shared perception is that the Hong Kong protests are doomed for failure. Joshua Lam, a second-year student from Hong Kong who has been closely following the situation, explains that “in this conflict the moderates are the student leadership and the Hong Kong government and the radicals are the locals who want absolute freedoms or even independence and Beijing who wants absolute veto power over who gets on the ballot.” When asked whether the local extremists in Hong Kong are likely to dominate the conversation on the ground, Lam pointed to a live televised debate between student leaders and top Hong Kong politicians, noting that after a seemingly unprecedented public discourse about their demands one of the debaters turned around and told supporters at the main protest site that the government “didn’t give us a material response or direction.” This oscillation between the different groups of protesters’ diverse range of opinions discourages incremental progress and instead serves as a warning to Beijing about the danger of allowing even limited freedoms. In a country like the U.S. with freedom of speech and open discourse, such protests pose philosophical questions about values, but in China, where there are no such privileges, certain practicalities take precedence. So let the protestors shout, and hold up posters, and make convincing oral arguments. Regardless of how big this revolution grows, who gives a crap? People in mainland China can’t know about it. Citizens of Hong Kong won’t work effectively together to support it. And the rest of the world simply won’t care until someone puts down an umbrella and picks up a rock.

David Grossman is a second-year in the College majoring in computer science.