I’m five-foot-one and weigh somewhere in the low nineties. I’m not bony, but I would agree with anyone who said I was thin. I’ve been underweight ever since I was born—but for many Asians, that’s not unusual.

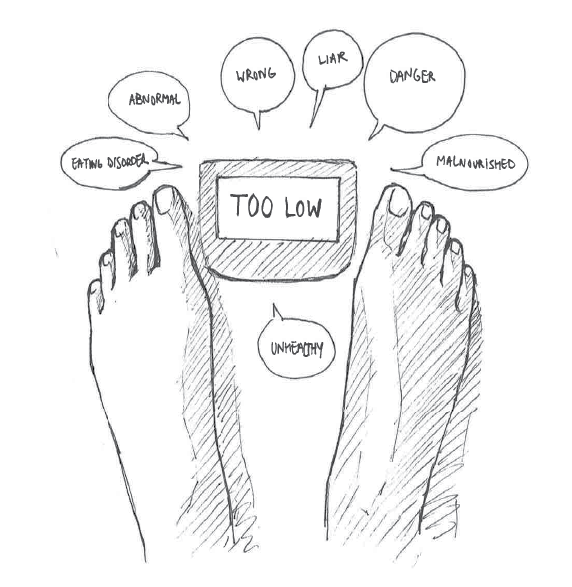

The other day I went into Student Health Services for a physical, in order to get a certificate of health signed so I could start a year-long teaching program in Japan—a job I had really wanted and was extremely excited about. The nurse weighed me, took my height and blood pressure, and then did a quick vision test. When the attending physician, a tall Caucasian woman, came in, she looked at my chart and said, “You’re wildly underweight.”

She reweighed me. Then she made me change out of my street clothes into a hospital gown, and weighed me on a different scale. This time the number was a pound lower.

“It says on your chart you have a history of mental illness?”

I had a bad feeling about this. “Second year, I was really stressed out about some things and paid some visits to Student Counseling,” I said. “But that was two years ago.”

“Did you leave with their approval?”

I frowned. “I guess. They never gave me a formal diagnosis.”

At the end of the exam the physician said, “I’m really concerned about you. You have a history of mental illness and you’re really underweight. Do you have an eating disorder?”

I’d sort of seen this coming. “No,” I said, trying to be patient. “I eat plenty. My mom is like this too. It’s more normal for Asian people—”

“No, no it isn’t,” she said.

“I know so many friends who have similar body types to me,” I said. “It’s genetic. My mom is the same—” and my brother, and grandma, and two of my aunts, and an uncle.

“Well, maybe your mom has an eating disorder too.”

I was stunned. Now she was questioning my mother, too? I looked at the form and reminded myself I had to get her to sign it. I tried to be reasonable.

“How much weight do you think I should gain?”

The physician did some calculations. “Fifteen pounds. If you gain fifteen pounds, you’ll be normal.”

I had never weighed that much in my entire life.

I tried again. “I don’t think I can gain fifteen pounds by the time it’s time to go to Japan—”

“Yes, that’s true.”

“But… I need you to sign the form.”

“I can’t if I have these concerns.”

“But that means I can’t go!”

“Well, I’m not sure that you should!”

I froze. The air seemed to thicken with tension. Was she kidding me?

“I’m normal,” I protested. “I have so many friends who are a similar height, a similar weight—”

“You’re in denial,” the physician said, shaking her head. “You’re being very resistant to the idea.” Her tone implied my attitude wasn’t helping things. Well, I didn’t like her attitude, either.

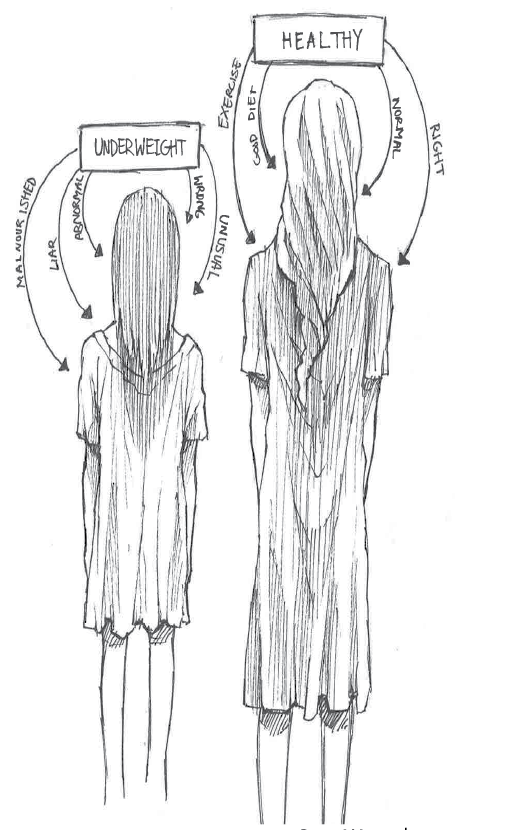

She made me sign me up for weight management visits. I walked out of the hospital and called my dad. Halfway through explaining what had happened (“She said I was too underweight. She won’t let me go to Japan.”) I started crying—she’d accused me of so much, hadn’t listened at all, and had even made me doubt myself. Maybe I was abnormal. Maybe I did have a problem.

My dad was furious.

“That’s ridiculous!” he said. “Fly home. Right now. I’ll find you a doctor. Fly home this weekend.” When he calmed down a little, he said, “Find an Asian doctor. You have to go to an Asian doctor.”

After I found a Chinese doctor at Northwestern who would give me a physical, I started looking at WHO statistics for Asian BMIs. For Asian populations, one study found, some BMIs under 25 (considered obese) still put Asians at higher risk for diseases related to obesity, such as hypertension, high blood pressure, or cardiovascular issues. In other words, this study suggested that some Asian people should naturally weigh a little less than the American norm to be healthy.

I talked to a few Asian friends who were about my height. They too, fell in my weight range. My old roommate, a spunky and athletic dancer who was a major foodie, also weighed in the nineties and was five feet tall. I had a friend in high school, an ex-gymnast, 5’4” and ninety pounds—lots of people were jealous of her fit body, but she ate like a truck driver. We worked in an ice cream shop together and always took home huge milkshakes and sundaes.

“That’s ridiculous,” these friends all said. “What, does she think half the people in Japan or Korea have eating disorders?”

Though the physician I saw accused me of being resistant to the idea that I was underweight, she was resistant to the idea that I really might just have been born this way. Aside from my weight, I was in perfect health, and had no symptoms of having a disordered relationship with food. I eat when I’m hungry, and I stop when I’m full. I don’t binge, purge, control, restrict, or count calories. But when I’d told her—angrily—“I’ve been like this for 21 years. I know my own body!,” she immediately assumed I was ignorant or lying, and invalidated my personal experience by replying, “I don’t think you do!” She demonstrated a complete lack of cultural awareness, bringing her rigid notions of what “normal” bodies should be like to bear on not only me, but also my mother, whom she hadn’t even seen.

She didn’t listen to anything I said.

And she isn’t the first. A few months earlier, I’d gone to Student Health to get treatment for a kitchen burn. The attending physician spent more time asking me about my weight, asking if I had an eating disorder, and trying to get me to come in for weight consultations than she did treating my red, throbbing, and blistered finger.

For the careless way in which “mental health” was entered into my chart without further elaboration and tests, for the way both physicians at SHS took that note and twisted it to apply their own unbending stereotypes and expectations on to me, and for the complete and utter failure of cultural competency they demonstrated in making accusations about my body and assumptions about my relationship with food,I am appalled. My visit with SHS shook my self-confidence so much that I forced myself to eat four meals that day, not stopping even when I was full, even when my stomach started to protest. I made twice my usual portion of rice, poured twice the normal amount of oil into the frying pan. Even after I finished my last meal I thought: “Should I keep going?”

They should not have made me doubt myself so much.

When I started talking to my other small-framed Asian friends, their stories started coming out too—of times non-Asian doctors had looked at them with very concerned faces and asked, “Do you have an eating disorder?” Those doctors didn’t believe my friends when they said no, either.

I, and thousands of other girls out there, shouldn’t have to find a special Asian doctor just to get a physical. Medical professionals should understand that different people have different body types. Diagnosing solely based on looks is harmful and even negligent on the part of the doctor, especially since our idea of healthy weight is based on norms for Caucasians. To properly address, and even prevent, eating disorders, physicians should gain a more fundamental understanding of all the symptoms an eating disorder entails—not just weight. Otherwise, some people who really need help will fall through the cracks and some who aren’t sick will be incorrectly diagnosed.

Angela Qian is a fourth-year in the College double majoring in English and political science.