Nationally, a recent wave of on-campus activism for fossil fuel divestment has pitted administrations against students who claim that colleges and Universities have greater moral responsibility in managing endowment resources than they recognize at present. In response, some administrations have taken steps to divest, but at the University of Chicago, this has not been the case. University President Robert J. Zimmer said at a meeting with The Maroon in June that the University’s Board of Trustees is “unlikely” to divest from fossil fuels.

On precedent and principle, Zimmer disagrees with divestment as a best practice. He said that the University’s role should be to produce climate change and energy use research, especially in partnership with Argonne National Lab, at which the University is the largest contractor.

When asked how much of the University endowment is invested in fossil fuel companies, Zimmer said, “I don’t know the answer,” adding that this was because the University Investment Office, chaired by Mark A. Schmid, invests in portfolios rather than in individual companies.

He said that the administration’s opposition to divestment is consistent with the Kalven Report, published by a University faculty committee in 1967, which recommended that the University maintain political neutrality in the interest of ensuring free expression. Zimmer said he had seen the addendum to the UChicago Climate Action Network (UCAN) 2013 divestment report, which argued that the social impact of climate change was, in the language of the Kalven Report, “so incompatible with paramount social values as to require careful assessment of the consequences.” However Zimmer also said that he did not find the argument “convincing, compared to the arguments the other way.” In reference to the addendum, he said, “I appreciate and admire that people went through the effort of making those arguments, and just because you make an argument doesn’t mean people accept it.”

“Investments are the responsibility of the Board of Trustees, and the University and the Board have long taken a position about divestment in general—that it’s not something that the particular views of some group of what’s politically important should be taken as the basis for, and that has been the ongoing view of the Board. And if you ask me, that’s the continuing view of the Board. So as I said, this is a Board matter, but if I had to report on my sense of the Board’s view of this—is that they’re unlikely to want to do that,” Zimmer said.

The student activist group UCAN has lobbied for divestment since late 2012. UCAN recommends that the University remove all endowment investments, including “commingled” investments in mutual funds, from the 200 coal, oil, and natural gas companies which emit the most carbon, as defined by Fossil Free Indexes, LLC. The list includes blue chip companies such as BP, ExxonMobil, and ConocoPhillips.

One of UCAN’s ongoing objectives is to schedule a meeting with the University’s Board of Trustees to discuss its platform. In April, the group held a protest after it said that Darren Reisberg, vice president and secretary of the University, had reneged on a written promise to secure a meeting between the group and at least one member of the Board of Trustees.

According to second-years Nadia Perl and William Pol, both co-directors of UCAN’s divestment campaign, the group has not yet contacted individual Trustees to schedule a meeting.

UCAN’s proposal has received broad student support; in a 2013 referendum, 70 percent of the student body who voted had voted in favor of divestment. After the referendum, the administration commissioned UCAN to write a report on the merits of divestment. Since its publication, the administration has not moved to divest.

For fourth-year Kristin Lin, a former co-director of UCAN’s divestment campaign who has since taken a self-described “advisory” role to the group, the goal of divestment is not to substantially injure the balance sheet of major companies, but to “galvanize” people to discuss the global social impact of climate change, including change on Chicago’s South Side.

“It is important to understand how divestment functions in a larger conversation and not to think of it as a panacea…UCAN also works for environmental justice, as climate change disproportionately affects minority and marginalized groups,” she said.

When Administrators Move

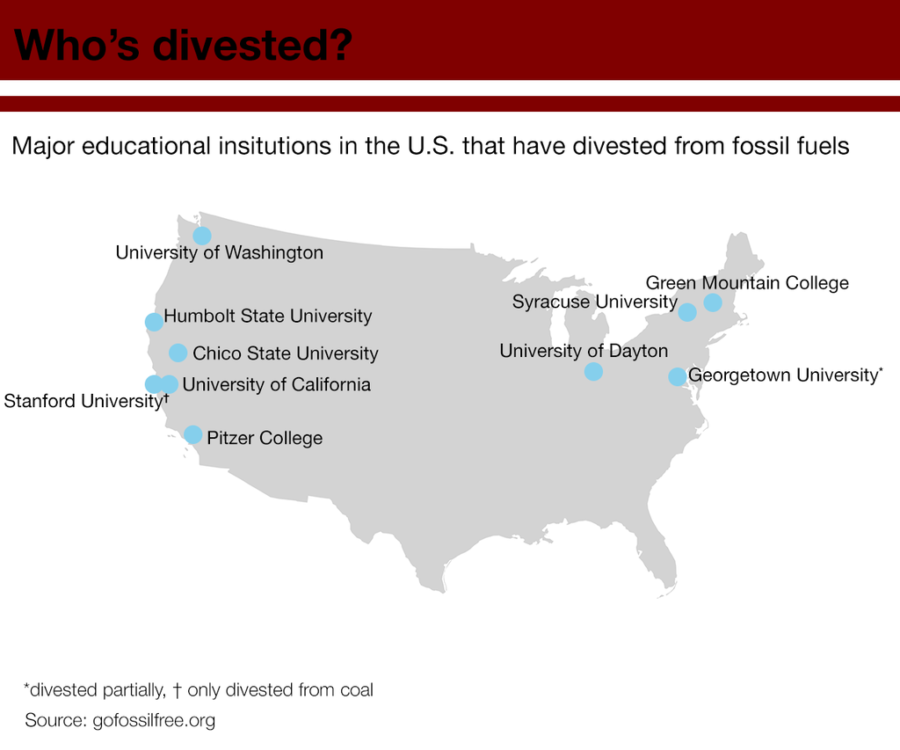

Other institutions have been more willing to budge on divestment, particularly with respect to holdings in coal. However, activists sometimes characterize administrative steps to divest as public relations gambits, as opposed to genuine commitments to social change.

In May 2014, Stanford University announced its divestment from coal, including mutual funds that contain coal companies. In a press release, the administration cited Stanford’s Statement on Investment Responsibility, which, unlike the Kalven Report, states that investment decisions may be made on the basis of whether the “trustees judge that ‘corporate policies or practices create substantial social injury.’” According to the statement, the administration noted that coal “generates higher greenhouse gas emissions per unit of energy generated than other fossil fuels,” and Stanford, by divesting from coal, was acting as a “Global Citizen.”

Michael Peñuelas, a Stanford undergraduate and member of the activist group Fossil Free Stanford (FFS), is skeptical of that explanation. Instead, he suggests, Stanford had few material or human resources invested in coal before the announcement.

“Stanford received almost none of its power from coal generation, and because of our geographical position, coal was also not a subject of research or research funding. Also, it was a financially savvy decision at that point in time, and remains so,” he said.

In Washington D.C., activists also suggest that administrators hold ulterior motives when they choose to divest. On June 4, Georgetown University announced its divestment from all direct holdings in coal, which exclude holdings in mutual funds. In a statement, the University cited its commitment to “real world sustainability solutions,” a need to “[respond] to the demands of climate change,” and the University’s values as a “Catholic and Jesuit University.” The move was approved by the University’s Board of Directors, which passed a resolution on the subject on the same day.

However, in the formal resolution, also dated June 4, the Board stated that “an insubstantial portion of the University’s endowment is now directly invested in companies whose principal business is the mining of coal for use in energy production.”

Caroline James, an undergraduate member of the activist group Georgetown University Fossil Free (GUFF) and the Committee on Investments and Social Responsibility (CISR), a 12-person committee of faculty, students, and staff, said, “That line makes me kind of nauseous every time I see it.”

“And just that phrasing, ‘insubstantial,’ makes the University’s course of action seem like a political move,” she added. James also said that the administration has repeatedly tried to “appease” divestment protesters by burying their activism in red tape.

Georgetown commissioned CISR in 2012. According to its charter, the committee is responsible for making recommendations against any University investments that are inconsistent with Catholic or Jesuit principles, or which underwrite “substantial social injury or involve a significant violation of human rights.” However, CISR itself cannot review, veto, or recommend specific endowment investments, as that power is reserved for the University’s Board of Directors.

James said that the CISR is “dysfunctional,” as it only meets over e-mail as opposed to in-person, and argues that it misinterprets its own charter.

“A lot of people on CISR are saying that it’s our job to encourage fossil fuel companies to invest in renewables, even though our ability to initiate change in a large company is doubtful, as we are small shareholders. There is a lot of fear around this issue, because it involves the endowment. I think that CISR shouldn’t worry about the endowment, because its charge is moral responsibility,” she said.

Plans for Advance

While they face a variety of institutional responses to their claims, divestment activists at Chicago, Georgetown, and Stanford are all still pushing for their administrations to divest from Fossil Free Indexes’ list of the top 200 resource extraction companies; they head towards action with a variety of plans and counterclaims.

For James, who said that the Georgetown administration attempted to anticipate GUFF’s protests by screening its members’ e-mail until the group moved its communications offline, a challenge is to avoid becoming disaffected.

“I try not to be cynical,” she said.

Peñuelas said that he disagrees with the idea that investments can be apolitical, as is implicit in the Chicago administration’s interpretation of the Kalven Report.

“I think that more generally, investments are political. The point that folks often make is that it does have limitations in the institutional context when the returns are going to such a broad group of people. But when you’re talking about the impact of climate change, I don’t think the limits apply.”

Editor’s note: Kristin Lin is a former editor of The Maroon.