The Smart Museum’s new exhibit, To See in Black and White, which opened October 1, is a diverse collection of black-and-white photography from Central Europe. The exhibit chronicles a half-century of innovations in photography from the World War era, during which the cultural ties between the U.S. and parts of Europe were disrupted by hostility.

“Political events occurred that led to us not actually having […] artistic exchanges and intellectual exchanges with that part of the world,” said Kimberly Mims, the curator of the exhibit.

The Smart Museum has been collecting Central European art since 2000 in hopes of exposing an American audience to the artistic innovations missed during wartime. To See in Black and White was made possible largely thanks to a recent bequest from the Lester and Betty Guttman estate.

The exhibit is a companion to the Expressionist Impulses show, which features paintings from the same areas and time period. Despite their shared backgrounds, however, the exhibits are quite different. Painters in the Expressionist movement focused on articulating the essence of reality, while the photographers of the era were more interested in capturing its particularities.

“At the time, there was this new idea of ‘New Objectivity’, a new way of looking, and some people looked at it to mean restrained and cooler,” Mims said. “It’s not emotive like Expressionism.”

The exhibit is split into five main parts, each presenting a different aspect of photography during the time period. Many celebrated photographers, including Walter Peterhans and John Gutmann, are represented in the gallery alongside many of their lesser-known peers.

The first section features six interpretations of portraiture. Each photographer has their own unique approach to capturing the subject: Grete Stern presents an intimate glimpse into a student’s facial features, whereas Walter Peterhans employs a cubist approach, photographing a man’s geometric accessories in Portrait of a Gentleman.

The next section on the left-hand wall showcases the increased use of photography in advertising, a field previously dominated by illustration. However, this new application of photography presented new problems, particularly when it came to incorporating the names of products into the art itself, as text could not be directly overlaid on photographs. In some of the photos, like Paris (Wine Bottle and Glass), the artist simply photographed objects with the words already printed on them. Other photographers took the concept even further and would manipulate the images in such a way as to superimpose the words. For Oskar Nerlinger’s World Matchsticks, the photographer developed a unique technique for burning words onto light-sensitive paper—a particularly appropriate method for an advertisement promoting a brand of matches.

Meanwhile, the back wall presents a more unique compilation of images centered around a collage by Hannah Höch that conveys themes of colonialism and the female form. This grouping, which the plaque describes as “deliberately quirky,” showcases photography from the first five decades of the 1900s while maintaining a thematic thread.

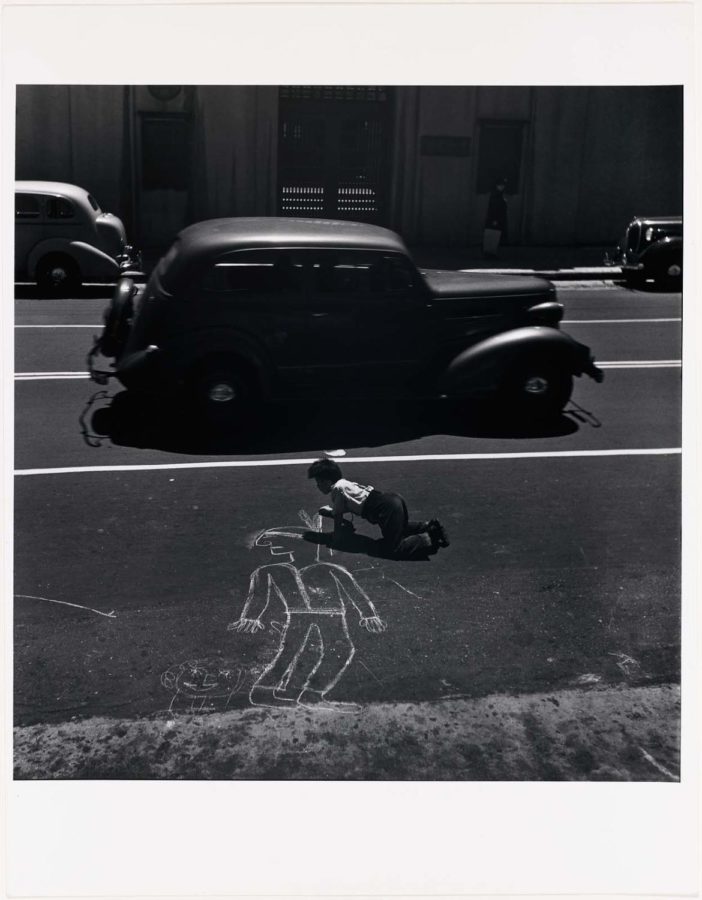

Along the fourth wall sits a collection of street photography and images focusing specifically on the texture of objects. “This is very nice for the connection with Expressionism because they were very interested in the dynamic city,” Mims said. John Gutmann’s piece The Artist Lives Dangerously, San Francisco is one of the strongest ties between the Expressionist movement and the New Objectivity movement: Although the style of photography is very precise, Gutmann focuses on the boundless and uncorrupted creativity of the young—a topic that also interested the Expressionists.

Finally, the centerpiece of the gallery is a large glass case that houses four photographs lying flat. “I wanted to set this idea of orientation as something of a selection,” Mims said. The four photographs range in style and subject matter, but they all convey unique messages based on the angle at which the viewer perceives them. One piece, for instance, shows a young girl’s reflection in a puddle, but depending on the viewer’s orientation, the part of the image that appears to be the “reflection” seems to reverse.

Although some of the artists featured in this exhibit have become relatively well known since the reestablishment of international relations, others are still emerging from obscurity. “Having [unknown artists] out there like this is an opportunity for people to explore them further,” Mims said. Now, 70 years after the end of World War II, American audiences have the chance to be introduced to them.

To See in Black and White runs through January 10th at the Smart Museum. Check the Smart’s website for museum hours.