In the midst of the recent events at Mizzou and Yale University that have exposed the inherent institutional racism upon which these universities were founded, #BlackOnCampus began to surface across social media. This hashtag emerged to give students of color on college campuses an opportunity to share the many ways in which their intellectual, psychological, and physical well-beings have been threatened, put under attack, or left unsupported. While these stories being told are all poignant and important, I find it imperative to highlight one woman’s story deserving of its own hashtag—perhaps #BlackOFFCampus. I want to bring greater attention to Georgiana Simpson (Ph.D. ’21).

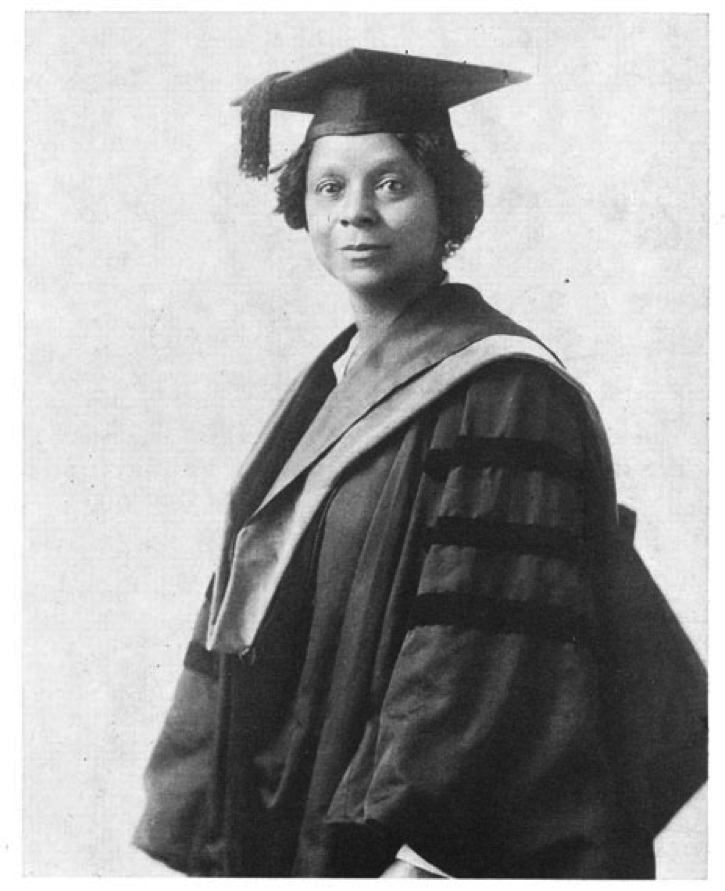

As the University of Chicago celebrates 125 years of “inquiry and impact,” I found it apt to involve myself in inquiring about the impact that African-American women have made on our campus. While walking on the quad, one may see the maroon banners hanging on the light posts. One reads: “Georgiana Simpson, a student of German Philology at the University of Chicago, and two scholars at other institutions become the first African-American women to receive Ph.D.’s from U.S. universities.” This, however, is not the full story.

The Special Collections of the University of Chicago Exhibition “Integrating the Life of the Mind” divulges the true nature of Simpson’s time at the University:

“An African American student from Washington D.C., Georgiana Simpson, had enrolled for a B.A. degree. She had elected to live in Green Hall, a women’s dormitory, but her arrival occasioned protests from several white Southern women students. Sophonisba Breckinridge, head of Green Residence Hall and secretary to Marion Talbot, dean of Women, made an executive decision that Miss Simpson could stay in the dorms. In response, five of the protesting students moved from the dormitory. Upon his return from summer vacation, President Harry Pratt Judson reversed this decision and asked Miss Simpson to find residence off campus, which she did. This established an informal policy that African American students could not live on campus.”

The University is socially prospering off of the very women they socially ostracized. Simpson is deserving of more than just a banner on the quad for wealthy donors to see and feel inspired to put a check next to the diversity box. If the University of Chicago is insistent upon using her name consistently as a marker of diversity in University promotional material, then it is time to reevaluate how the University honors Simpson. She deserved to be black on our campus, something she wasn’t allowed to do. The best way to honor Simpson now, after the mistreatment she endured here, is to place a monument on the very campus from which she was forced to flee.

The purpose of telling Simpson’s story is to raise awareness, because that’s the thing about consciousness—once something is known, it finds a place and settles down. You can try to deny it, ignore it, and even forget it, but you cannot get rid of it. Since learning of Simpson, I have become immensely burdened by that which I cannot un-know. This burden has been relieved by the various women and other allies eager to have women acknowledged through a monument, one of which would not just be the first of its kind on the campus of the University of Chicago, but in the entire city of Chicago.

Honoring Simpson properly through a monument will most likely not happen during my time here. This is a fact of which I am well aware, but I hope that one day, when I attend alumni weekend with my children, I can take them on a tour of the Dr. Georgiana Simpson Residential Commons.

Shae Omonijo is a second-year in the College double majoring in political science and public policy.