The final months of 2015 were something of a mixed bag for the Chicago Symphony Orchestra (CSO). The orchestra’s 125th anniversary season has certainly come with perks. Its survey of pieces premiered by the CSO has lent historical context to the concert-going experience—it’s never been easier to get lost in the anecdotes and materials provided in the program books—and the orchestra’s commitment to offering 125 free concerts around the city this season alone is nothing short of admirable.

Unfortunately, these historical nods have been waylaid by stodgy programming on the whole, leaving it up to the orchestra to provide the interest—or not, depending on the evening.

Thursday’s all-German program was, too, a stable of warhorses, but it showcased the explorations that are possible when you bring in new friends. On the podium was English conductor Jonathan Nott in his second-ever CSO engagement; the evening’s soloist, the superb German-Canadian cellist Johannes Moser, is also an infrequent collaborator, having last played with the CSO in his 2005 U.S. debut. The results were impassioned, zesty, and memorable, a good sign for the first concert of the calendar year.

An effusive rendition of the Academic Festival Overture kick-started the program. Under Nott’s fluid, easy baton, the orchestra played Brahms’s mélange of student songs with youthful vigor.

This energy carried over into Haydn’s Cello Concerto in C, featuring Moser as soloist. Overshadowed by its D-major successor for two centuries, Haydn’s first foray into the cello concerto literature was long assumed lost until it was unearthed in the Prague National Museum in 1968. Buoyant and engrossing, the C-major stands as a worthy companion to what has been renumbered as Haydn’s second cello concerto.

Moser’s interpretation brought together everything one could hope for in a performance of this work: finessed melodic lines, adroit finger work, arresting yet unpretentious virtuosity, and a dash of cheeky wit. Interacting with the orchestra through grins and glances, the magnetic 36-year-old united the hypersensitivity of a chamber musician with the flair of a virtuoso soloist. A first movement of perfect Haydnian charm was followed by an achingly gorgeous second movement, all topped by a nimble third-movement Allegro which showcased Moser’s sheer technical facility.

The CSO ought to be applauded for its intuitive ensemble work: at moments when Moser threatened to be lost in the wide-open acoustics of Orchestra Hall, Nott and an accommodating Classical-sized orchestra sensitively adjusted to his lines.

Strauss’s autobiographical Ein Heldenleben occupied the second half of the program. Like many a Strauss tone poem before it, Ein Heldenleben was enthusiastically received upon its U.S. premiere by the CSO in 1900. Such was the rapport between Strauss and the CSO that when he visited Chicago to conduct the orchestra in 1904, when American orchestras were held in low esteem in Europe, the German conductor composer is reported to have said, “I came here in the pleasant expectation of finding a superior orchestra, but you have far surpassed my expectations. I am delighted to know you as an orchestra of artists in whom beauty of tone, technical perfection, and discipline are found in the highest degree.”

Strauss’s praise could have just as easily applied to the CSO Thursday night. Taut with operatic drama, its full-bodied performance of Ein Heldenleben breathed life into Strauss’s leitmotifs, from the mercurial violin solos representing Strauss’s wife, soprano Paulina de Ahna, to the sharp-edged woodwinds and low-brass grumbles of Strauss’s critics, to the orchestra’s intrepid “hero” theme, standing in as Strauss himself. He even writes in a parade of his own heroes: snatches from his tone poems Till Eulenspiegel, Don Juan, and Don Quixote enter, interweave gorgeously, then exit stage left.

Ein Heldenleben seems at first to be the nostalgic remembrances of a man in the final years of his life. Not so—Strauss was only 31 when he composed the piece—but the CSO played the work with a tenderness that would have convinced one of the contrary. Especially arresting were concertmaster Robert Chen’s exquisite solos; with its nearly concerto-esque devotion to the solo violin and, by association, Pauline, Ein Heldenleben could just as easily be titled Eine Heldenliebe.

Even a rocky ending—in which the first horns audibly struggled to hit the subterranean low E-flat—couldn’t mar this truly heroic performance. Here’s to 2016.

Pierre Boulez, 1926–2016

A footnote in Thursday’s program book quietly noted that Moser’s debut with the CSO was conducted by none other than the iconoclastic Pierre Boulez, who died last Tuesday at his home in Baden-Baden. He was 90.

The news is a somber postscript to last year’s Boulez jubilee, when the French conductor-composer received a Lifetime Achievement Grammy Award and orchestras around the world—the CSO included—celebrated his 90th birthday with commemorative concerts.

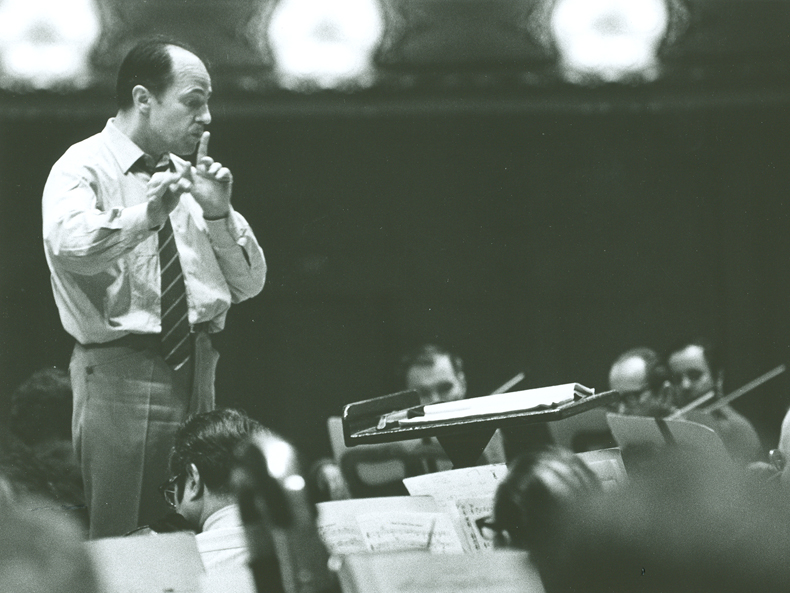

Boulez’s long, illustrious relationship with the CSO began in February 1969 with programs of music by avant-gardists Anton Webern, Alban Berg, Olivier Messiaen (Boulez’s teacher), and Boulez himself. He would go on to make a whopping 49 recordings with the CSO; eight of the 26 Grammys given to Boulez over his lifetime were awarded to recordings he’d made with the orchestra. He was named the CSO’s principal guest conductor from 1995 to 2006, and then its first and only Helen Regenstein Conductor Emeritus—the title he held upon his death.

Boulez’s passing was acknowledged onstage during Wednesday’s Afterworks Masterworks concert and in a published statement by CSO Music Director Riccardo Muti, who praised his “great musical artistry and exceptional intelligence.”

Though well-received in Chicago, Boulez was a divisive, even incendiary force in the music world. In his twenties, he tallied Arnold Schoenberg’s shortcomings in an infamous 1952 essay (“Schoenberg is Dead”). Fifteen years later, in an interview with Der Spiegel, Boulez made headlines again for not-so-subtly implying that opera houses—bastions of the conservatism he so loathed—be blown up. Trouble followed him to his stint as music director of the New York Philharmonic, where his quixotic attempt to expose audiences to contemporary music ultimately proved too bitter a pill to swallow.

Adversaries dismissed Boulez as an arrogant young firebrand with a public persona as prickly as his music. Rather than repent, Boulez embraced their assessment. “Certainly I was a bully,” he confessed to The Daily Telegraph in 2008. “[But] I’m not ashamed of it at all. The hostility of the establishment to what you were able to do in the 1940s and 1950s was very strong. Sometimes you have to fight against your society.”

And fight he did, for good reason. Unfortunately, the state of affairs Boulez bemoans in his Der Spiegel interview—a stunted standard repertory which seems to begin with Mozart and sputter to a stop at Berg—could just as easily describe the present-day programming of leading opera companies, nearly 50 years later.

While he lived, Boulez defended the music of today more valiantly than most have, or probably ever will. Few were simultaneously so adored and reviled, because few had so much at stake. Ultimately, he may have followed Schoenberg to the grave, but so long as his raison d’être remains unfulfilled, Pierre Boulez is not dead.