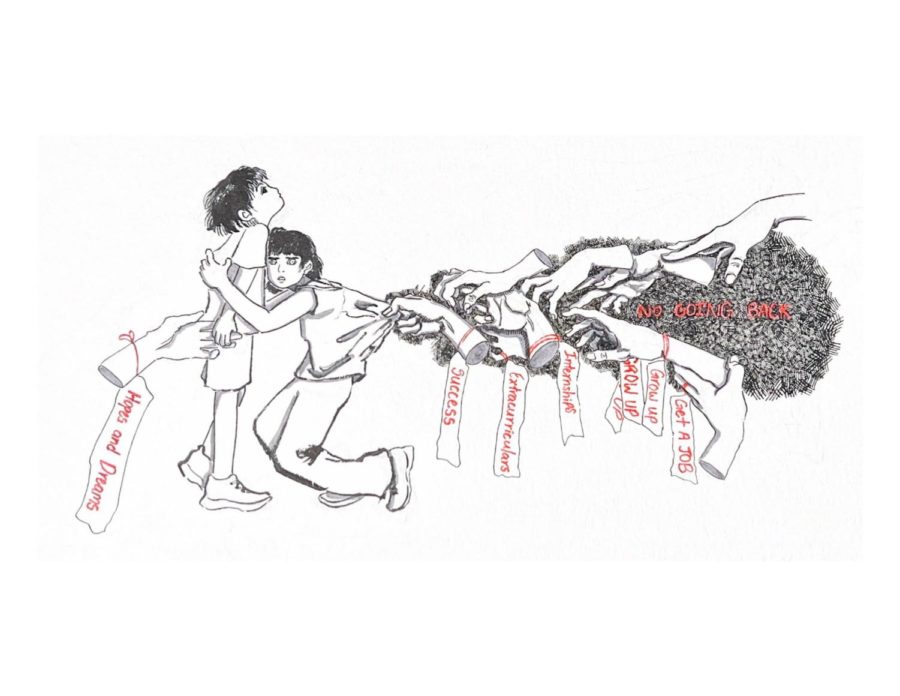

If someone knocked on your door in the middle of the night, would you answer it? If you opened your door to find a cold, dejected soul looking for a bed and a bit of food would you let them in? Would you feed them? What if there was a family at your door? What if there was a four-year-old girl with dreams of learning to read; or an old man, sick, tired, and hungry; or a mom, desperately looking for a home for her family; or a man scarred from war? Would you answer them? Would you let them in? Would you bear their burdens as your own? How far would you go?

Europe faces these questions as it attempts to deal with an increasing influx of migrants from across Africa and the Middle East. These people, members of a contingent of 60 million displaced individuals, are the product of the collapse of Arab nationalism under the immense weight of ethnic, tribal, and religious tension. Increasingly, the ancient boundaries of sovereign states have become meaningless as their governments sow their own destruction in the pervasive understanding that the state is no longer capable of or willing to enforce the formal rights of its citizens.

Hobbes claims that war can only be prevented by a contract between citizens and their government. An individual enters into an agreement with their sovereign and each of the other citizens to ensure peace, but this contract is only valid insofar as the sovereign is capable of maintaining the safety and security of each citizen. The Arab governments’ inability to provide these rights to their constituencies has in effect invalidated the Hobbesian political obligation of the citizen to the sovereign. This void of power has led to a state of struggle, in which complex entities of individuals, organized ad hoc on the ground, endeavor to secure their own rights and sovereignty.

The geopolitical implications of this struggle and the increasing pressure on the region due to macroeconomic headwinds and sinking oil prices have ensured that large portions of the affected populations have been stripped of their practical rights, their safety, and their economic security. These individuals, the migrants of the modern era, face terror at home, but their plight may be almost as dire in the countries where they are headed.

Though international law protects refugees—asylum-seekers fleeing conflict or persecution whose claims have been approved—migrants, defined as individuals who have moved for economic or other reasons, don’t receive the same guarantees. All refugees are migrants, but not all migrants are refugees. The myriad causes contributing to the expulsion of migrants from their homes blurs this fine line between refugees and migrants and further complicates the situation.

In 2015, Europe fought to deal with the more than one million migrants streaming into the continent. Nationalist sentiments brewed, many countries closed their doors, detention centers cropped up, and fines and deportations became commonplace. At the same time that the migrant crisis tested the economic capacity of nations to absorb large numbers of ailing individuals, it tested the resilience of the European Union as a legitimate governing entity. The Schengen Agreement, one of the centerpieces of European integration, which eliminated border crossings and allowed for unimpeded, visa-free travel among certain countries, was threatened by the vast numbers of migrants moving unchecked throughout the continent. The Dublin Regulation, which mandated that migrants remain in the first country they enter, was loosely enforced, if at all, and many countries, unused to coping with waves of migrants, reinstated border crossings and other forms of migration deterrents.

In the years leading up to World War II, individuals all across Europe—so-called “minorities”—were increasingly stripped of their rights by nationalist entities governing sovereign nation-states. Though the League of Nations attempted to institute formal rights for these individuals, it failed on a practical level and the many individuals recognized as “minorities” became, in effect, “stateless.” They became neither refugees nor migrants—they were simply unwanted. Stripped of all the rights they had held as members of a society, these people were the same ones that were eventually driven into detention centers, concentration camps, and gas chambers.

The situation today is markedly different from the one then, but there are inevitable and grave implications of denying migrants the right to enter and coexist in Europe. The EU and other nations need to coordinate a response to the crisis without infringing on the rights of individuals who deserve support.

Nicholas Aldridge is a first-year in the College.