In her talk, “Accountability for Sexual Violence,” for the Law School’s Domestic Violence Project on Wednesday, University of Chicago distinguished law professor Martha Nussbaum addressed legal precedents and university challenges but not her January Huffington Post blog post, “Why some men are above the law.” While the blog post was clearly on the table, it wasn’t substantively discussed until the off-the-record question and answer session afterward.

In that post, Nussbaum tells us that, in her own personal “Bill Cosby tale,” she did not pursue justice. For many victims, that’s an understandable and wise response, but Nussbaum then goes on to commit a logical fallacy. She generalizes from that one experience and gives blanket advice to all others raped by famous men. “Move on,” she says. “Do not let your life get hijacked by an almost certainly futile effort at justice.” Then, in her post liked by 2,500 Facebook users, UChicago’s Ernst Freund Distinguished Service Professor of Law and Ethics concludes: “Forget the law.”

Nussbaum believes she made a good decision for herself, and she may have, but that doesn’t mean her decision would be right for everyone else. Every assault is unique. Every perpetrator unique. Every survivor unique. Every vision of justice unique. We need to honor each survivor’s unique path to healing and recognize that what’s right for one survivor is not necessarily going to work for all others.

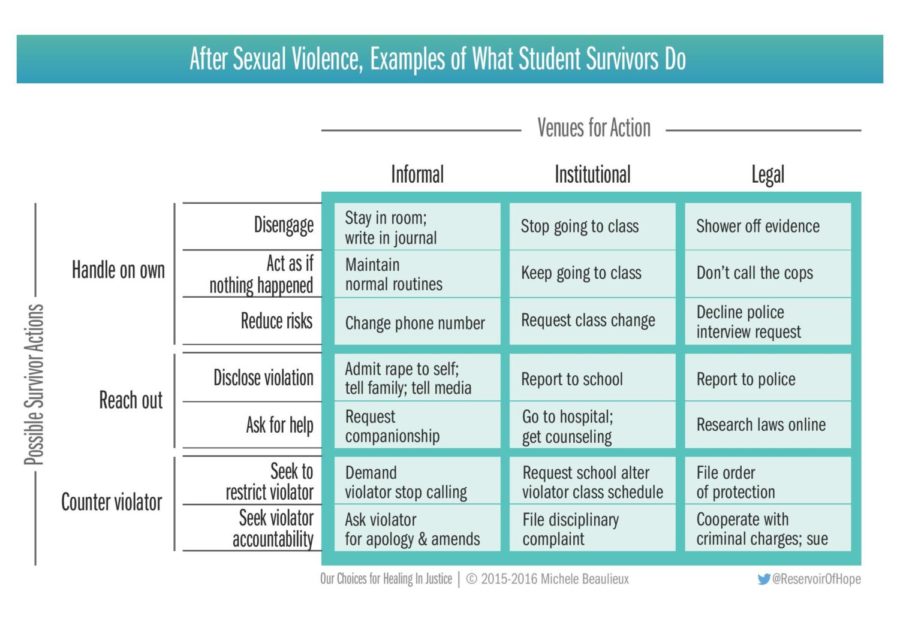

Survivors, myself included, have an overwhelming array of choices. We need to choose not only what to do but also where to do it. To help people understand and navigate choices after sexual violence, I’m developing a “decision explorer,” Our Choices for Healing In Justice, based on the PrOACT decision-making framework.

In Smart Choices: A Practical Guide to Making Better Life Decisions, John Hammond, Ralph Keeney, and Howard Raiffa describe the basic elements of decisions with the acronym, PrOACT, which stands for Problem, Objectives, Alternatives, Consequences, and Tradeoffs. The matrix above, “After Sexual Violence, Examples of What Student Survivors Do,” is a highly simplified representation of alternatives. The fully expanded version has hundreds of cells relevant to survivors in workplaces and homes as well as schools and other settings.

Survivors have three basic possible actions. Firstly, they can handle the situation on their own as Nussbaum did and counsels others to do. Such personal coping may involve disengaging, acting as if nothing happened, and reducing risks. Survivors can also reach out, disclosing the violation and asking for help. Finally, they can counter violators by seeking to restrict or hold them accountable. Each of these actions can happen in informal and institutional venues in addition to the legal space that Nussbaum tells survivors to avoid.

At first glance, Nussbaum’s advice to survivors to “forget the law” is understandable. The legal system, in its present state, is problematic. It’s fair to warn survivors that, with the low probability of successful litigation, the legal system can constitute a second victimization. Some may, nevertheless, choose to counter the violator using law enforcement and the courts. Whether or not survivors’ legal tribulations provide vindication, they may sleep better at night, knowing they tried to protect others from assailants likely-to-continue violence.

Others do “forget the law,” but that doesn’t mean they need do nothing. Nussbaum equates justice and the legal system, but the legal system is not our only venue for justice. Survivors—and we’re not, as Nussbaum implies, only women—can take action in informal and institutional venues as well as, or instead of, legal ones. It is precisely because the law is so problematic that survivors find other options for getting a modicum of justice. For example, while the statutes of limitations for most Cosby survivors have expired, many are speaking out in the court of public opinion. Also, many student survivors are getting school accommodations mandated by Title IX.

One reason some people are above the law is because of advice like Nussbaum’s. She doubts society will stand up to power and tells survivors that seeking justice is futile. Nussbaum is wrong, and the fact that Nussbaum herself is powerful—a well-respected, influential thinker with a substantial following—makes her stance particularly distressing.

I much prefer the perspective of a professor at the university across town: that no man should be above the law. Jeffrey Winters, a political science professor at Northwestern University and the author of the 2011 book Oligarchy, notes that “one of the greatest challenges in history has been to create legal governing institutions that are stronger than the strongest people in society.”

A good first step would be creating spaces at the table to dialogue on the topics on the table. No one should be able, in Winters’ words, to deploy “their wealth and power to free themselves of constraints that others in society face.” Some people will stand up to power—sometimes at great personal cost—and survivors can find justice. Indeed, experts are recognizing an unprecedented and accelerating trend of sexual assault victims speaking out.

Let’s hope this tide is a turning point. While we work to reform the legal system, we may need to be creative in how we define and pursue justice. Let’s keep the law, imperfect as it is, but also expand our definition of justice beyond it. Each unique survivor should be able to choose among the full array of possibilities.

Michele Beaulieux, A.B. ’82, curates news about sexual assault at facebook.com/cultureofconsent. Follow her on Twitter at @ReservoirOfHope.