On a crisp evening in the middle of the academic quarter, a University official stepped up to the podium. He thanked everyone for coming and explained that the University wanted to meet with “the general public on matters of mutual interest and concern.” During the event, staff shared their perspective on civic engagement while community members also provided feedback.

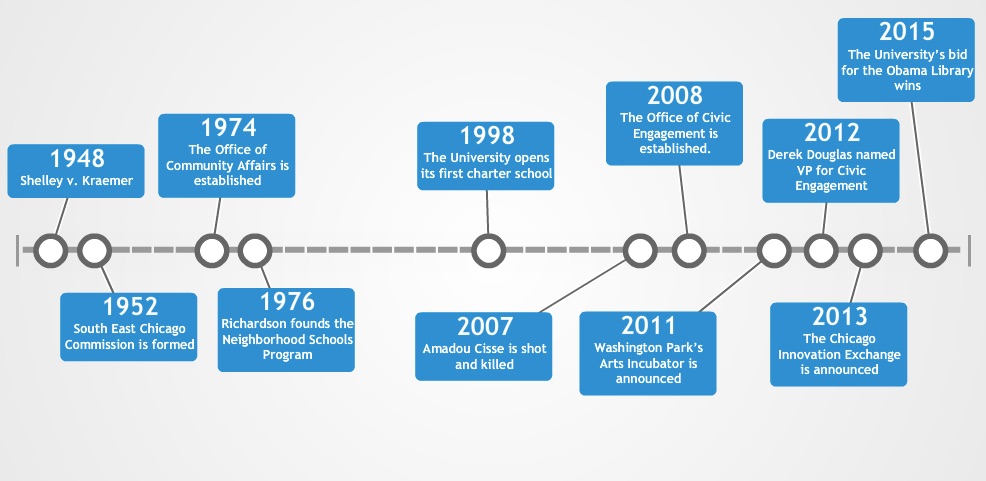

Was this March 17, 1952 or October 27, 2015? On the first date, the University was 62 years old, and this was the first time that University officials, community leaders, and the general public—an estimated amount of 2,000 Hyde Park–Kenwood residents—had gathered to discuss issues like crime prevention and law enforcement, according to two sociologists who described the meeting in their 1963 book The Politics of Urban Renewal. As a result of the public’s expressed concerns and pre-meeting conversations in the administration, the South East Chicago Commission (SECC) was formed shortly thereafter to “act as a listening post for our entire community.”

Flash forward to 2015. The vice president for civic engagement, Derek Douglas, stepped up to the microphone to welcome a crowd of approximately 50 University staff members and community members in a celebration of the University’s 125-year history. On this night, a similar topic for discussion is on the table: civic engagement at the University of Chicago for the next 125 years. Over the next two hours four panelists spoke about how the University has supported their church, research, nonprofit, and schools, respectively. Later, Office of Civic Engagement (OCE) staff members and the attendees participated in a roundtable discussion.

“[T]his idea of being outwardly engaged…defined who we were,” Douglas said. “We all in this room know that the University’s relationship with the community over the years has ebbed and flowed, and there were times where the commitment and focus were stronger, and times where it was not so strong. But I’m proud to say that today…I think that commitment to partnership, to community and civic engagement, is as strong as it’s ever been.”

Creating a Space

On a recent fall morning, the Currency Exchange Café was a hub of relaxed activity. Customers, many who have come to the café on the recommendation of a friend or a cousin, sit at the mosaic-topped tables as R&B music plays in the background. Outside, CTA riders wait for the #55 Garfield bus and the Green Line on their commutes. The University’s renowned director of arts and public life, Theaster Gates, has meticulously designed the openness of the space and its aesthetic as a double take on the Currency Exchange storefront that previously occupied the location just about 16 months ago. Next door is Gates’s new arts-focused bookstore and wine bar Bing. On the other side is the Arts Incubator, a similar venture by Gates as a “space for artist residencies, arts education, community-based arts projects, as well as exhibitions, performances, and talks,” according to the website.

The University owns this building, along with other parcels of land along Garfield Boulevard. In 2008 it began to quietly purchase different plots of land in the Washington Park neighborhood, which borders the Hyde Park campus. At that time, the University was silent about exactly what it was trying to do—even to the alderman.

“My concern is that this grabbing of land at this point without any clear idea of what they want the land for or need it for is not appropriate,” Third Ward Alderman Pat Dowell told WBEZ’s Natalie Moore at the time. “I would like them to participate in a very public community planning process, where they are one stakeholder of many stakeholders to try to determine what that corridor will look like.”

A few years later, this property would be proffered by the University for as part of its bid for the Obama Presidential Library, an opportunity for economic revitalization of the community. How the University chose to engage with the community would play a large factor in determining this revitalization.

Foundations of civic engagement

The first slide that Douglas presented at the event stated two University presidents’ attitudes for community relationships. This demonstrated that this issue has been on the table of University policy-making since its founding in the 19th century—albeit with some changes over the years.

William Rainey Harper, president from 1891 to 1906, once stated: “A university which will adapt itself to urban influence, which will undertake to serve as an expression of urban civilization, and which is compelled to meet the demands of an urban environment will in the end become something essentially different from a university located in a village or small city…. [I]t will ultimately form a new type of university.”

Douglas shared a similar sentiment from current president Robert J. Zimmer on the PowerPoint presentation: “Through partnerships, we’re able to benefit from knowledge and assets in the community, and combine those with our own capacity and expertise. Together, we’re able to do much more than either of us would be able to do alone.”

This is the kind of thinking that has informed the civic engagement policy since Douglas arrived in 2012. His office developed a target region of nine “mid-South Side” neighborhoods surrounding the community: Hyde Park, Kenwood, Oakland, Douglas, Grand Boulevard, Washington Park, Greater Grand Crossing, Woodlawn, and South Shore. Douglas also pointed out that the OCE wants to make an impact both on the South Side and around the world. He cited the foundations of this new approach as:

1. Upholding the University’s core values, connecting the University’s unique work and location as an anchor on the South Side;

2. Pursuing opportunities for mutual benefit between the community and the University;

3. Building and leveraging external relationships—”we have to partner to do this kind of work,” Douglas noted; “we have to listen, learn, be transparent, and be accountable;”

4. Having an impact on a local and global scale, including UChicago’s presence through its centers in Delhi, Beijing, and Paris.

“It’s trying to speak to the idea of, how do we make civic engagement a part of the DNA of the University, not just a side project?” Douglas said.

In an interview, Zimmer echoed his vice president’s statement. “I think the key approach to thinking about this for us is that there are partnerships to build that are a benefit to the community and a benefit to the University by doing them,” he said. “What you discover is you become a kind of magnet and you’re able to pull in a significant amount of energy that exists in the community and you’re able to focus it.”

While there have been a number of recent initiatives introduced under the leadership of Douglas and his predecessor to spark and sustain community relationships, it hasn’t always been this way.

Bad blood

The University strove to secure faculty members as Hyde Park residents and boost undergraduate enrollment in the 1950s. Previously, between three and four out of every five faculty members had lived within a one-square-mile radius of campus. However, a steady stream of faculty began to leave the University—many with young families—and they named their dissatisfaction with the community as a factor. The University considered several responses, according to UChicago sociology professor Andrew Abbott (A.M. ’75, Ph.D. ’82), which even included pulling up stakes in Hyde Park and resettling in Evanston with Northwestern as an undergraduate school and UChicago as the graduate division. Making a commitment after that March 17, 1952 meeting, the University organized the SECC and launched an official planning unit—the first in a number of steps to strategize how to improve the caliber of housing, businesses, and general quality of life in the area.

This plan would come to be an omen of the University’s interactions with the community for years to come. Urban renewal—though “not as brutal as you were seeing at the same time on the East Coast” according to Abbott—involved moving approximately 2,000 families and individuals out of their Hyde Park homes so that other developments, such as the shopping center on 55th Street and Lake Park, could be constructed. This moving was also partially the result of a Supreme Court decision overturning racially restrictive housing covenants, legally allowing black people to move to areas that previously had been inaccessible to them. Those who were financially able were moving out of the communities surrounding Hyde Park into more prosperous, safer areas farther from the city, according to Abbott.

“[But] that moving never stopped, and then what it left behind was empty space,” he said. “In Woodlawn there were 75,000 people when I came here in 1971. There are about 25,000 people in Woodlawn today. [Because the black population kept moving] it’s just empty.”

The University’s previous actions supporting restrictive covenants had set the stage for adversarial relationships between the institution and the community, however. Mary Pattillo, a professor of sociology and African American studies at Northwestern who received her Ph.D. from UChicago in 1997, explained, “The University…gave personnel and money to homeowners associations and other organizations that put racially restrictive covenants in place. This created bad blood between black communities and the University of Chicago.”

The University’s strategy for urban renewal signaled a move toward racial integration—but not socioeconomic integration. “The urban renewal project definitely planned for racial integration, but it wanted to do so [in terms of]… racial integration of middle class people,” Pattillo added.

The SECC also wasn’t transparent in its actions, contributing to distrust in the community. A well-informed but unnamed SECC board member is quoted in The Politics of Urban Renewal as saying: “The university with the help of the commission has continued to make enemies through the kinds of land purchase and building purchase practices they have engaged in. Even old, established residents of the community have discovered recently that the university has been quietly buying up every available middle-income house….None of this has been carried on with any awareness of the consequences it leads to—hostility toward the university or the commission.”

Branching out with education efforts

Over the following decades, University officials slowly began to engage with the community in a more positive manner.

“It’s been my experience that the Office of Civic Engagement has gradually immersed itself in improving the quality of life in the neighborhoods that surrounded it,” said Rudy Nimocks, a longtime Woodlawn resident, former UChicago Police Department chief, and the OCE’s current director of community partnerships. He said that one of the most significant steps in this process was the 1968 introduction of local kids to University classes through a program blending academic enrichment and the kids’ passion for sports. This later became formalized and expanded as the Office of Special Programs.

The 1970s and 1980s witnessed a tremendous growth in the number of programs for relationship-building between the University and the community. This was particularly due to the work of Duel Richardson (A.B. ’67), the founder of the Neighborhood Schools Program, and Jonathan Kleinbard, the vice president of the OCE’s predecessor, the Office for Community Affairs (the office itself was founded in 1974). In particular, Kleinbard was “a pivotal personality,” said Nimocks, who came to the University in 1989 after Kleinbard wrote him a Christmas card wishing for Nimocks to lead the UCPD—for 10 Christmases in a row.

“Kleinbard managed community relations in a way by being invisible. He did all the arranging behind the scenes,” Abbott said.

Abbott, a 45-nonconsecutive-year resident of Hyde Park, came to the University as a graduate student in 1971. “Nobody left Hyde Park,” he said. “It was astounding. You went to the Co-op, and you saw your dentist, the guy who gave you a B+ in a course last week, and your dissertation adviser.” Risks to public safety appeared to be prevalent in the neighborhood itself: when the shuttle system was launched in 1973, one of the drivers was shot at Harold’s in the initiative’s first week. The University sought to assuage fears and promote a culture of community.

“Hyde Park is, as residents proudly proclaim, a stable, racially-integrated community where people live together in, if not outright harmony, a level of peaceful co-existence atypical of the rest of the city,” a 1987 Chicago Tribune feature on Hyde Park noted.

“This is a residential neighborhood where family living is emphasized,” Kleinbard is quoted in the feature. “This is not the swinging North Side. This is where families set down roots and have a community life together. People pause to talk to each other on the streets and ask how [each other’s] kids are doing in school.”

Kleinbard and Richardson’s teamwork shone through in one of the oldest civic engagement activities of the University: the 45-year-old Neighborhood Schools Program (NSP). According to Nimocks, Kleinbard visited the principal of Kenwood Academy after hearing of University faculty members’ disappointment with their kids’ education at the school. With Richardson’s help, he decided to send University students to assist with tutoring in the classroom. And so NSP was born, which now boasts more than 400 University students tutoring between 5,000 and 6,000 public school students across the OCE’s nine target neighborhoods.

The Hyde Park bubble

For Shaz Rasul (A.B. ’97, M.S. ’08), a former NSP-er and now director of the program itself, there’s more that can be done. “For me, the dream is still a University student in every classroom,” Rasul said. “Can you imagine growing up in Woodlawn, and in nine years meeting nine different University students from nine different places having conversations about astronomy, physics, and anthropology?”

Rasul started his UChicago undergraduate career volunteering with his house to play chess and do homework with kids from Woodlawn schools. Now, he’s formally the OCE Director of Community Programs. These include the Community Programs Accelerator, an initiative rolled out last year providing nonprofits with technical assistance and creating a network among the members.

Like Abbott, Rasul found that his fellow students opted against venturing outside of the neighborhood, for community service or even entertainment and dining. “If you were leaving Hyde Park you were going downtown. There wasn’t a lot of business or commerce in those days that kept you in the neighborhood,” he said. However, there were “pockets of people” who actively engaged with the community, noting the establishment of the then-student-run University Community Service Center in 1998.

Nate Silver of FiveThirtyEight (A.B. ’00) drew attention to this insularity recently when he published an article about Chicago’s segregated diversity: “When I was a freshman at the University of Chicago in 1996, I heard the same thing again and again: Do not leave the boundaries of Hyde Park. Do not go north of 47th Street. Do not go south of 61st Street. Do not go west of Cottage Grove Avenue. These boundaries were fairly explicit, almost to the point of being an official university policy.”

Yet despite qualms with the safety of these neighborhoods, the University took an active role in their education offerings with the launch of its charter schools in 1998. The University opened its first campus, in North Kenwood–Oakland, that summer, with students from across the South Side. “The charter aims to serve the community by providing it with a school that has greater parental interaction and higher expectations from the students, said [school director Marvin] Hoffman,” the Hyde Park Herald noted in an archived article.

For OCE staff member Sonya Malunda, the opening of the charter school signaled a “renewed commitment” to community engagement under then-University President Hugo Sonnenschein and then-Vice President for Community and Government Affairs Hank Webber. It was the motivating factor for her to join the OCE staff. Eighteen years later, she serves as the senior associate vice president for community engagement.

“The University’s role was really that of a junior partner, working with community leaders, the city, and residents to both create visions for these neighborhoods as well as to lead specific projects,” she said. “I would say our work in education was probably one of our most significant contributions at that time.”

As UCPD chief, Nimocks also saw the importance of quality public education in building a vibrant neighborhood. When the location of the charter school was being finalized, he extended UCPD jurisdiction to cover that area to mitigate parents’ safety concerns—hopefully encouraging them to plant roots in the community.

Douglas’ New Model

While the University continued to build out its civic engagement through various resources, other issues—including safety—were still on the table. It came to a head in 2007, when graduate student Amadou Cisse was shot and killed in an attempted robbery while walking to his off-campus apartment at East 61st Street and South Ellis Avenue early in the morning.

A Grey City article from that time reported on a public forum with UCPD leaders and students after the death: “Some voices at the meeting worried that the increased police presence following the killing would cause more harm than good and possibly alienate residents in the surrounding communities. But for the most part, the students’ comments pointed to a deeper anxiety: For many on campus, the shooting confirmed their worst fears about their neighborhood’s safety.”

The University announced plans for immediate steps the UCPD would take in response. They added vehicles to the late night van service program, increased the number of UCPD bicycle patrols, and permanently doubled the police presence between midnight and 8 a.m.

The University also made several changes to the long-term strategy of public safety. These included bringing AlliedBarton security officers to campus in 2009 and building light towers on the streets crossing the Midway Plaisance in 2010. Two years later, a different Grey City article noted crime rates in 2010 and 2011 in Hyde Park and Kenwood were some of the lowest in decades.

Around this same time, the city of Chicago was preparing a bid for the 2016 Olympics, and in a few years a former law professor would be preparing his own bid for the White House. (The Office of Civic Engagement was also formally established, replacing the Office of Community Affairs in 2008.) These two events presented unique opportunities for the neighboring Washington Park: a sports stadium and a presidential library, which would likely engage Garfield Boulevard, which connects the UChicago campus to the Dan Ryan expressway.

“The gateway from Garfield Boulevard has been important to the University for a very long time….If you put in University of Chicago in GPS it would likely send you down that Garfield Boulevard corridor. We made some land purchases there, and we said that we wanted to find mutually beneficial opportunities between the University and the community,” Malunda said.

In addition to these changes, the University saw an internal opportunity: In 2012, they hired Douglas, President Obama’s senior adviser on urban policy, as the next Vice President for Civic Engagement.

“One of the things that President Zimmer asked when I first took the job was…to think about creating what he called a new model, our model, of civic engagement,” Douglas explained during the October event. “One that was rooted and grounded in the historical work but was also thinking forward about what we wanted to do. One that was more connected to the everyday work, the fabric if you will, of the University of Chicago but also connected to the community as well.”

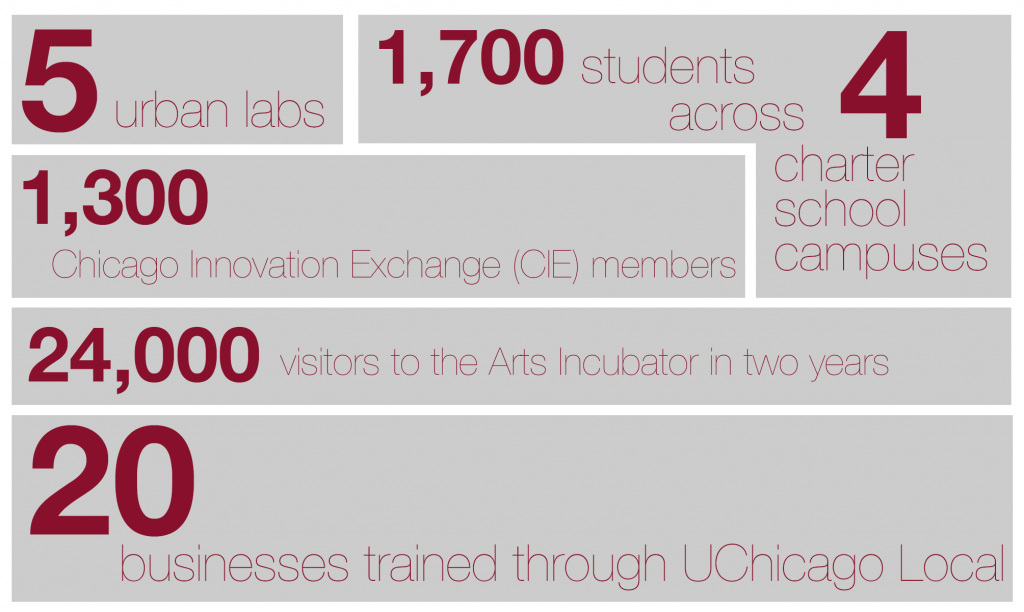

Since his start at UChicago, Douglas has revamped the OCE’s thinking to focus on four pillars of civic engagement: anchoring neighborhoods in the mid-South Side, extending education in terms of capacity building, expanding urban research, and fostering entrepreneurial innovation. “When I initially started I think we were kind of laser-focused on…leveraging the University’s role as an economic entity on the South Side,” Malunda said. “What we’re doing now is we have significant activity in each of those four areas, which [Douglas] brought the vision of expanding.”

This included everything from training rising professionals in nonprofits and government offices through the Civic Leadership Academy to promoting a cohesive identity of local institutions, including the Frank Lloyd Wright Robie House and the Museum of Science and Industry, through the formation of the official Museum Campus South concept. Additionally, Becoming a Man, a community program to mentor at-risk youth and build positive values that was closely studied by the Crime Lab, has now been adopted nationally by President Obama’s administration under the name of My Brother’s Keeper—and this is only in the past year.

Douglas’s vision of civic engagement hasn’t just been programmatic expansion, however. In the past few years, tangible proof of the OCE’s work exploded, especially in neighboring Washington Park.

Community response to Obama library, trauma center

Reminiscent of the backlash against SECC’s lack of transparency in the 1950s, the University’s bid for the Obama library encountered unexpected hurdles in gathering community support in the first round because of its privacy.

In December 2014, it leaked from the foundation charged with planning the Obama Presidential Library that the University of Chicago’s bid—the presumed frontrunner—might be in jeopardy because the University failed to explain how they would acquire the public parkland they were offering as a site. The Chicago Sun-Times’ Lynn Sweet wrote, “The University of Chicago strategy to win the library and museum—never officially asking the Chicago Park District for the land and keeping its sites secret until recently in order not to stir up public protest—is on track to backfire….[B]ecause the university has been so secretive, the public has no idea how many acres are involved.”

The University’s bid also faced the backlash of the Friends of the Parks who fought the University’s efforts to seize public parkland. As the group wrote in an editorial, “To support this land grab, have University of Chicago officials unequivocally demonstrated that their 11-acre adjacent site is too small for the library, particularly when the only other urban presidential library—Boston’s John F. Kennedy Library—is well accommodated on 10 acres? Is the [Park District] board aware that the university’s recent poll about taking parkland never asked the community whether they would support putting the library solely on the university’s 11-acre site and did not take public parkland?”

Douglas, the OCE team, Mayor Rahm Emanuel’s administration, and community members rapidly assembled in an attempt to salvage the bid. They staged rallies and music videos in support of a South Side center. Torrey Barrett, the founder and executive director of Washington Park’s KLEO community center on Garfield Boulevard, was one of those community members. He said he was committed to bringing the library to Chicago and especially to Washington Park, but he has reservations about how the University has conducted itself throughout the bidding process.

“The University had an advisory…group they created to help them lobby for the library,” he said, choosing to describe it as a group rather than an advisory board. “We did radio interviews, testified at public hearings, newspaper articles, television, media blitzes all about why Washington Park should have the library—why the University of Chicago’s bid was the best bid. It was a good process, but the problem is now that the University of Chicago has been chosen, the meetings stopped. Now no one is talking about it.”

The University also encountered fierce protests from community members regarding the establishment of a South Side trauma center. The University of Chicago Medical Center shuttered its center in 1988 because of the financial strain on the University. Protests regarding this matter have escalated in recent years, with members of the Trauma Center Coalition (TCC) and the on-campus group Students for Health Equity (SHE) drawing attention to the University’s refusal to reinstate its center despite the investment it was willing to make for the Obama Presidential Library. In September, the University announced a joint trauma center with Sinai Health System’s Holy Cross Hospital on the West Side, but many TCC members say this isn’t enough.

“A Different Kind of Game”: UPenn’s civic engagement

The University of Chicago isn’t the only university to face challenges in civic engagement. The University of Pennsylvania has encountered similar arguments and, like UChicago, has spent much capital in the past two decades working on redefining its role as an anchor institution.

“Because they can make a difference in the lives of their neighbors, colleges and universities have a moral and ethical responsibility to contribute to the quality of life in their communities,” stated a 2014 report entitled “Effective Governance of a University as an Anchor Institution” in a handbook for university administrators and officials.

In 1993, UPenn spearheaded this idea by creating a Center for Community Partnerships to work directly with local public schools. The Office of Government and Community Affairs still today hosts monthly “First Thursday” meetings to promote transparency and discussion between community members and staff members. UPenn also developed the West Philadelphia Initiatives as a university-led, multi-pronged approach to address the issues of safety, housing, commercial and real estate development, economic development, and education.

Current UPenn president Amy Gutmann acknowledged the success and continued strength of these efforts in her inaugural address in 2004: “No one mistakes Penn for an ivory tower. And no one ever will….We cherish our relationships with our neighbors, relationships that have strengthened Penn academically while increasing the vitality of West Philadelphia.”

As times have changed, other universities adapted with different approaches, and some have chosen the option of putting up barriers rather than engaging the community. As Abbott noted, “It’s inevitable that the University starts to play a different kind of role because the whole game [of civic engagement] is a different kind of game.”

“A Vibrant Community Full of Possibilities”

Is the University writing the new playbook? While the OCE has undergone significant transformations in the past few years, the University and its partners have simultaneously learned how to adapt to the new needs and issues of the surrounding communities.

In contrast to Nate Silver’s days where University brochures warned new students not to venture outside the UCPD boundaries, this past September, Orientation Week staff encouraged first-years to see themselves as residents of the South Side. Staff at the University Community Service Center (UCSC) and OCE orchestrated the updates to these new City Life Meetings, which student O-Leaders facilitated as a part of the mandatory O-Week curriculum. They distributed the South Side Weekly’s annual Best of the South Side issue to every first-year, used a segregation map of Chicago from The New York Times to discuss the city’s racial makeup and diversity, and asked first-years to think about a university’s role in civic engagement. In another stark change, the UCSC also led walking tours for first-years to Woodlawn and Washington Park, the very same areas students were once told to avoid.

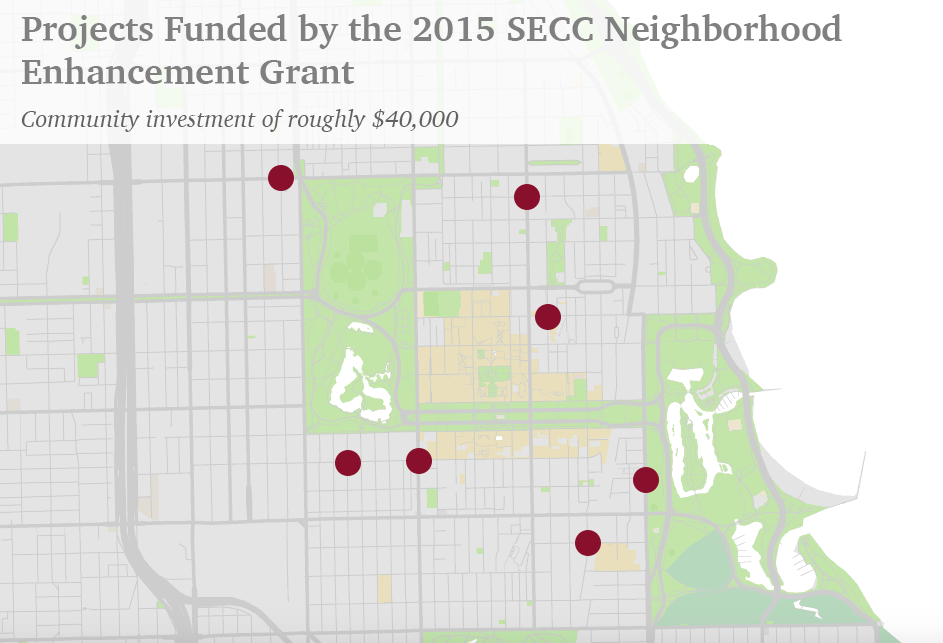

Additionally, today the SECC is drastically different from the SECC of the 1950s. Independently run and advised by a board of community members, the SECC is “all about creating a space that is welcoming and inviting. The goal ultimately is to not only sustain businesses that are there, but encourage others to come,” said Wendy Walker Williams, the executive director of the SECC since 2010.

The commission welcomes a variety of community input as well—over the past couple years, Williams and her staff have met with the aldermen in each of the communities surrounding Hyde Park to nail down a way that the SECC could assist in enhancing business corridors with different improvements. For example, this meant that in Woodlawn on East 61st Street from South Cottage Grove to South Martin Luther King Drive, lamppost banners declaring “Woodlawn: A Vibrant Community Full of Possibilities!” soon appeared. In Washington Park, the SECC assisted in coordinating a 51st Business Association Festival. “The point of a good festival is to bring people to a particular place to get comfortable with their community,” Williams said.

Williams also works to gauge community support by turning to her 24-member board, which meets the second Tuesday of every month. Members are selected by neighborhood to ensure that each area targeted by the SECC—Hyde Park, Kenwood, Oakland, Washington Park, and Woodlawn—have equal representation. While the nonprofit commission’s primary funder is the University, Williams said it also receives funding from the city of Chicago, the Chicago Community Trust, other private donations, and tax revenue from the Hyde Park Special Service Area (SSA) district—some of the very businesses that they serve. Williams emphasized that the SECC and OCE are separate entities.

“They’ve presented a few projects to us that the board has had really good feedback that they implemented,” she said, but added that they are not afraid of pushing back.

Now what?

The communities that comprise the mid-South Side—Hyde Park, Kenwood, Oakland, Douglas, Grand Boulevard, Washington Park, Greater Grand Crossing, Woodlawn, and South Shore—are about to experience a new era of civic engagement. The coming of the Obama presidential museum and library and the expansion of Gates’ projects on Garfield Boulevard promise further University involvement, for one. People are both excited and skeptical about the change it could bring.

“Where do I see [civic engagement] going? They’ll continue to engage the community as they have been, and they’ll continue to focus on the economic development that they want to focus on…so that’ll be a great corner of King Drive that’ll be an entryway into the University,” Barrett said. “[But] they should be working with organizations like KLEO and the Washington Park Consortium to look at a master development of the entire area….I am very concerned about gentrification happening. Gentrification happens when you have an institution-led development as opposed to a community-led development.”

Pattillo, the Northwestern professor, said the city should take the lead in establishing public housing options to avoid gentrification in Washington Park while University developments would inevitably drive up land value. “One of the most important ways to slow gentrification down and to allow people to stay and a neighborhood to improve is housing,” she said.

On the other hand, Zimmer is confident about building the futures of community members by expanding their skills through University programs. “I don’t believe seriously that there’s a big danger [of gentrification] there; I think our goal is to help build up local capacity more than anything else,” he said. “These programs are designed to create local capacity so that people in the community can do things themselves….I think the Obama library is going to offer a lot of opportunity for that.”

Nimocks sees the future of OCE as two-pronged: quality public education and safety. “A neighborhood cannot really accelerate its development unless they have good public safety,” he said.

Malunda looks forward to increasing student civic engagement. “Our doors are open—if community members or students have ideas that they would like to flesh out and vet with us, we are here [at] OCE to be a resource to them,” she said.

At the community event in October, Douglas had shared his dream for the OCE with these questions: “How do we make civic engagement a part of the DNA of the University? … How can the University be a catalyst to strengthen these neighborhoods?”

Perhaps the answer can be found in the remark of a panelist at the event, Pastor Christopher Harris of Bright Start Church of God in Christ in Bronzeville. After growing up on the South Side feeling at risk of arrest if he walked on UChicago’s campus, Harris said that today he sees a clear contrast in civic engagement:

“This University really does want to not only listen, but actually pay attention to what the community is saying and empower the community. Because at the end of the day, we have a responsibility to make sure this University is a resource to the people right within its reach.”

Correction: The article previously implied that the UChicago Crime Lab created the Becoming a Man program. However, it was actually developed and run by a group called Youth Guidance while the Crime Lab studied and evaluated the program.