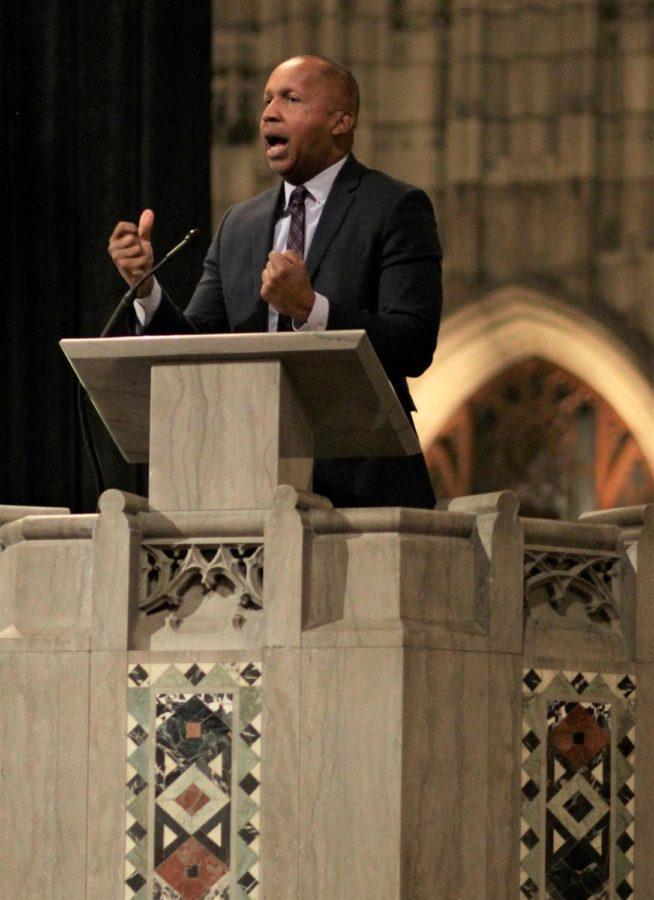

On Monday evening, a leading advocate against injustice in the criminal justice system delivered the keynote address during the annual Martin Luther King Jr. Day celebration at Rockefeller Chapel, speaking from same pulpit from which King spoke in 1956.

The celebration has been a tradition since 1990. Past speakers include President Barack Obama in 2002, then a senior lecturer in the Law School.

This year’s speaker, Bryan Stevenson, is a public interest lawyer and law professor at the New York University School of Law, founder and executive director of the Equal Justice Initiative (EJI), a MacArthur “Genius” Fellow, and author of a bestselling memoir, Just Mercy. The New Yorker named Stevenson’s viral TED Talk about injustice one of the five key TED talks.

The Chicago Children’s Choir performed before he spoke, singing iconic songs of the Civil Rights Movement such as Sam Cooke’s A Change is Gonna Come. The Reverend Jesse Jackson, keynote speaker at the 2015 celebration, made a surprise appearance on stage, singing with the children.

Fourth-year student Elizabeth Adetiba delivered opening remarks that addressed the event’s theme, Why must we continue to sing this song?

“Why must we continue to sing this song? An all too poignant question given the current state of our society. For centuries, marginalized communities in this country have been subjected to the song of racism, classism, homophobia, transphobia, and state violence. It is a song that has claimed countless lives, from the strange fruit hanging in the trees during Jim Crow, to the lifeless bodies brutalized by those charged with protecting and serving them…. A song that preaches the myth of disposability—that there are certain classes of people who are just not worthy of justice or second chances,” she said.

University President Robert Zimmer spoke briefly and addressed “the companion values of diversity and inclusion,” which he praised as central to both King’s vision and the University’s mission.

Stevenson began his talk by citing statistics on mass incarceration in America. He said that the United States’ prison and jail population has skyrocketed from 300,000 in 1972 to over 2.3 million individuals today. He stressed the particular burden of women’s incarceration rates, stating that the number of women going to prison has increased 646 percent and that 70 percent of those women are single mothers whose children are displaced by their imprisonment.

Stevenson said that “the statistic that keeps him up latest at night” is the Sentencing Project’s report that one in three black males born today will be incarcerated in his lifetime.

He moved on from numbers and statistics as he urged the audience to “get proximate” to real stories and get to know the people affected by injustice, and launched into stories from his law career that moved many audience members to tears.

Stevenson emphasized the importance of narrative and social consciousness in overcoming the myriad forms of injustice he named. “I hear people talking about the Civil Rights Movement and it’s starting to sound like a three-day carnival,” he said. Stevenson pointed to Rwanda and Germany as countries that have successfully integrated their histories of genocide into social consciousness, creating public monuments and fostering deep historical awareness. “We ought to talk about the fact that we’re a post-genocidal society,” he said.

Stevenson views the construction of public monuments and historical awareness as key ways to overcome problematic racial narratives. EJI is currently raising money for just such a project: a memorial to victims of lynching in Montgomery, Alabama.

“I don’t think the great evil of American slavery was involuntary servitude. The great evil of American slavery was this narrative of racial difference, this ideology of white supremacy, that we made up to legitimate our enslavement of other people,” Stevenson said.

“We haven’t talked about this legacy of terror and what it’s done…. The reason why we have all this widespread poverty and despair, the reason why the South Side of Chicago and our urban communities in the north and west, has to do with terrorism. Because the black people who came to Chicago, the black people who came to Detroit, to Los Angeles, and Oakland, and Cleveland, and Gary, Indiana, the people did not come to these communities as immigrants looking for new economic opportunities. They came to Chicago and cities like Chicago as refugees and exiles from terrorism.”

The University’s commemoration of Martin Luther King Jr. Day continues next Saturday, when the University Community Service Center will dispatch more than 200 volunteers to different service locations around Chicago, and historian Timuel Black and Senior Lecturer Bart Schultz will lead a bus tour tracking King’s legacy in Chicago.