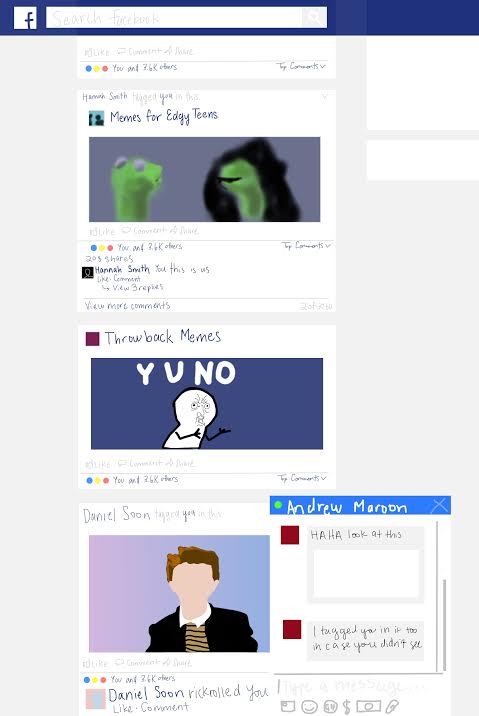

Remember the 2007 Internet phenomenon of Rickrolling, where users are tricked into watching the music video of Rick Astley’s “Never Gonna Give You Up”? From the ubiquitous “One Does Not Simply” photos to “Y U No” and now the Hooded Kermit, memes have become an irreplaceable part of our culture, in part due to their accessibility but also due to their ability to translate what we cannot articulate into a relatable unit.

Memes are short, simple, and funny. Coined by Richard Dawkins in the 1990s, a “meme” denotes an idea or behavior that spreads from person to person. You can look at them as a microcosm of evolution; their survival depends on popularity and usage. They can undergo changes and mutate into entirely different meanings. Take the Hooded Kermit. Countless sardonic “mutations” of catchphrases have come into play to adapt to cultural shifts while the fundamental “biological” unit, the original picture of Kermit, remains. The memes that are repurposed the most will enjoy the most success, and those that do not will inevitably fade from our collective memory. It’s a brutal but honest process: It is the purest form of democracy, where memes are chosen by a jury of young and old, rich and poor, on the basis of their perceived popularity.

Discussing memes’ scientific relevance, however, fails to explain why we like them so much. We like them because they are pointless, relatable, and mundane. In a time where content on Facebook changes rapidly, fake news merges with real news, and global issues play out right in front of our eyes, we are constantly inundated with information. The world moves, but memes stay to offer up perspectives on the human experiences we share with each other. We use them because they make us laugh until our sides hurt. We use them because they make the mundane marvelous. Memes bring our attention to the situations in life we never truly notice but participate in every day: They are snapshots of the past that exist in the present. Faced with Trump’s inauguration, fluctuating oil prices, and the potential repeal of the Affordable Care Act, memes serve versatile roles. They make these global headlines satirically relatable and provide a safe haven from an increasingly intimidating world.

Because of this flexibility, memes often seem to merely divert attention from current issues. Though they can be a form of escapism, memes also provide a way for us to reflect on ourselves. In a study published in the Journal of Business and Psychology, 74 Australian undergraduate students in an introductory management course were tested for their persistence at a Human Resource task. The students were split into three groups: one group watched a humorous video clip, another group watched an emotion-neutral clip, and the last watched a peaceful video clip. After watching their respective clips, they were asked to solve an unsolvable task: they had to make performance predictions of potential employees in a hypothetical company based on the employees’ personality profiles. Tasked with making 10 consecutive correct predictions, they were allowed to stop at any time. The group that watched the comedic video made twice as many predictions in the subsequent task and spent significantly more time working on it than participants in the other two categories.

The humorous clip, rather than distracting the participants, actually gave them the persistence to fully devote themselves to the task before them. Memes, because of their innate flippancy, are unfairly dismissed as inappropriate and distracting. Their ubiquitous imitation (mimema) across cultures has constructed a bridge to make our diverse and often fragmented experiences unified and relatable. Memes don’t draw us away from life; they pull us towards it. In President Obama’s final speech to his family, he told them, “you took on a role you didn’t ask for. And you made it your own with grace and with grit and with style, and good humor.” In a world where the unexpected can occur everyday, the best we can do is to take it in our stride with a little humor.

Jasmine Wu is a second-year in the College majoring in economics and philosophy.