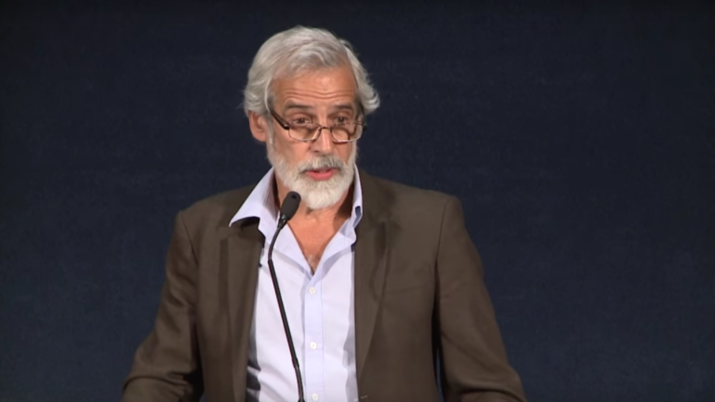

In an interview with The Maroon, Jamie Kalven, founder of the Invisible Institute, argued for civil action based on the findings of a Department of Justice (DOJ) report released in mid-January on systemic failures within the Chicago Police Department (CPD).

A journalistic production company advocating for civic empowerment, the Invisible Institute primarily oversees local issues like these. It partners with the Edwin F. Mandel Legal Aid Clinic of the Law School, collaborating with Law School professors like Craig Futterman.

Kalven believes that the report can be used as an asset by the general public and civil rights lawyers. “It was welcome to have the DOJ here, they would’ve done some good things, but it’s not within their power to do what needs to happen at the local level. That can only be driven by a community-based, local political process,” Kalven said.

The DOJ released the report on January 13, after announcing the investigation on Dec 7, 2015. According to the DOJ’s website, the report’s findings reveal that “the CPD engages in a pattern or practice of using force, including deadly force, in violation of the Fourth Amendment.”

The report attributes the alleged use of unconstitutional force primarily to two factors within the CPD: deficiencies in officer training and ineffective accountability systems. The CPD’s current methods of responding to misconduct allegations and reporting data on faulty officers were also reported as factors in the department’s underperformance.

The DOJ found concern regarding racially discriminatory behavior exhibited by CPD officers—a practice that is speculated to be due to ineffectual officer training. The report said that predominantly black and Latino neighborhoods are most affected by discriminatory and excessive force practices. However, it did not explicitly connect discriminatory behaviors to officer training practices.

Kalven argued that being able to cite the report as evidence of systemic flaws within the CPD is a powerful asset to both the general public and civil lawyers. The report doesn’t necessarily establish a city precedent, but it does acknowledge the difficult conditions investigative journalists and activists have been pointing out for years. In this sense, he said, the ability to make progress has improved.

The CPD has implemented reforms in the past. Since the DOJ’s initial announcement of the investigation, the CPD instituted a body-camera policy and established an anonymous hotline for its employees to report misconduct, among other changes.

In order for the CPD to introduce reform, a consent decree, or federal court order, is required. Currently, the City’s compliance under the consent decree is undergoing review by “an independent monitor” in agreement with the DOJ, according to the Justice Department’s website. However, Kalven has concerns regarding how effective the decree might be under the new administration.

With the advent of Jeff Sessions’s nomination as the new attorney general, Kalven foresees little to no federal oversight of problematic police departments.

“We don’t have the national government as an ally in the process anymore, but we have a lot of capacity to move the process forward here. And this is where it has to happen; Washington can assist, but we have to do it,” Kalven said.