Two undergraduate physics students at the University of Chicago recently led the discovery of a new method for levitating objects using heat.

Fourth-year Frankie Fung and third-year Mykhaylo Usatyuk managed to levitate objects up to one millimeter in size in the Chin Ultracold Lab at the Gordon Center for Integrative Science, including small glass and ceramic spheres, lint, dust, and ice particles.

Their findings could help researchers interested in microgravity environments or multi-body interactions design new experimental setups. According to their paper on the method, “levitation of particles in ground-based experiments provides an ideal platform for the study of their dynamics and interactions in a pristine isolated environment and has broad applications in fundamental and applied sciences.”

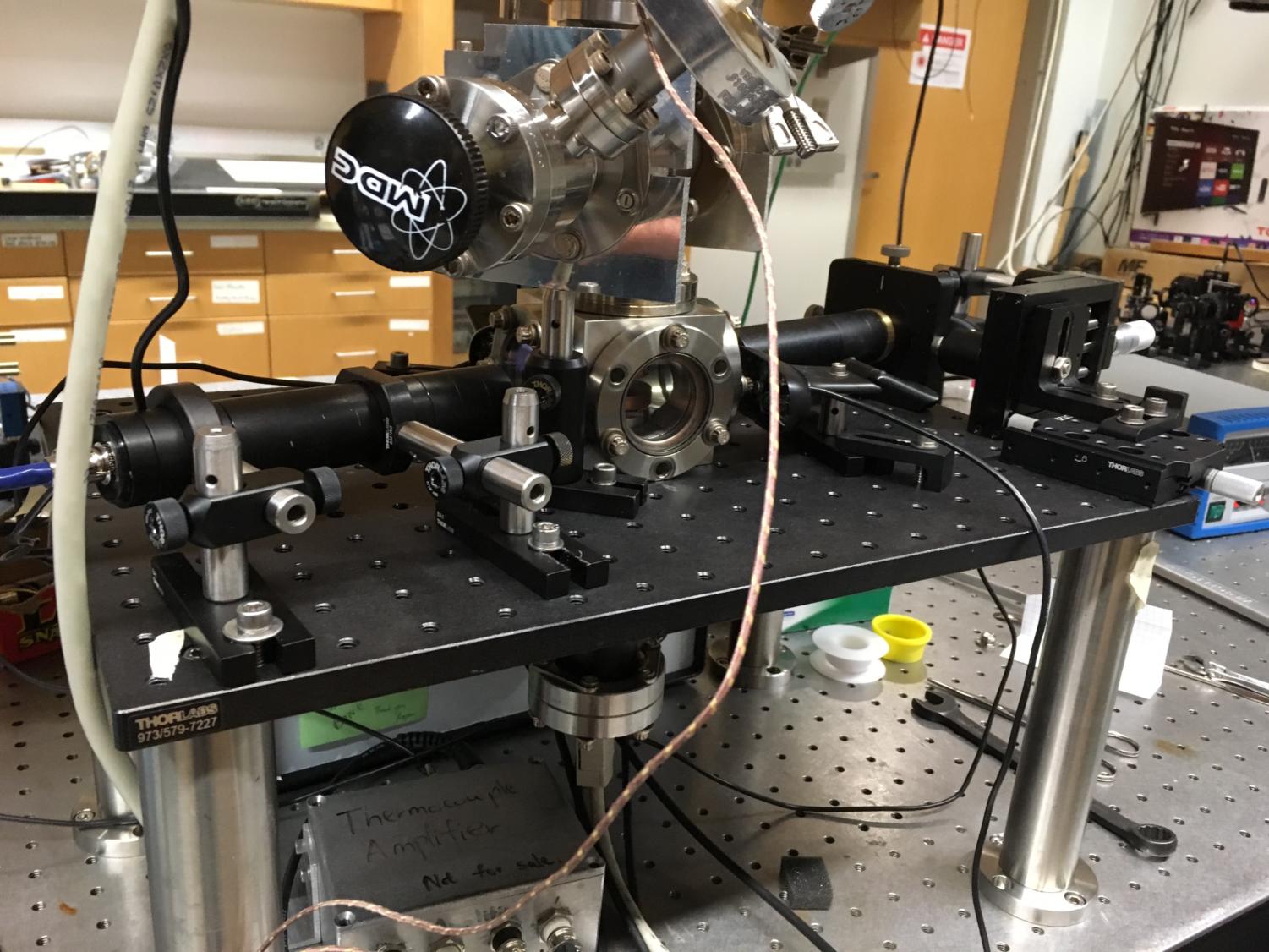

The setup involves placing a small object in a vacuum chamber between a lower hot plate, which is heated to between 277 and 298 K (37.4–77 degrees Fahrenheit), and an upper plate, which is cooled to 77 K (–321.07 Fahrenheit), and lowering the pressure to 1–10 Torr (between 760 and 76 times less than pressure at sea level).

The levitation relies on thermophoresis, a phenomenon describing the movement of particles in a temperature gradient. Because warmer air particles tend to have a greater velocity than colder air particles, they can sometimes “push” small objects away from a source of heat.

In Fung and Usatyuk’s setup, the two plates form a temperature gradient, which creates a thermophoretic force upwards.

“Air particles near the bottom plate will be warmer, and particles near the top plate will be colder. And so they have different energies, so when the particles are coming from the bottom and they hit, say a little bead or whatever, they’ll give it more energy, they’ll give more momentum, whereas the particles coming from the top, when they hit [it], they’ll give a lower momentum,” Usatyuk said. The momentum transferred from the bottom particles is enough to counteract the force of gravity and levitate the object.

Both Usatyuk and Fung learned of this opportunity by reaching out to professors they were interested in working with. Usatyuk was initially interested in ultracold atoms, so he applied for a position at Chin Lab, which specializes in ultracold physics. “It was sort of random,” said Usatyuk, who stressed that undergraduate opportunities typically depend on funding and the number of graduate students working on a particular field.